Pain in the hips and low back are common reasons people visit doctors and physical therapists. These professionals are often tasked with identifying a cause for the pain. Unfortunately, in many cases their explanations are unjustified, oversimplified, unhelpful, or simply wrong.

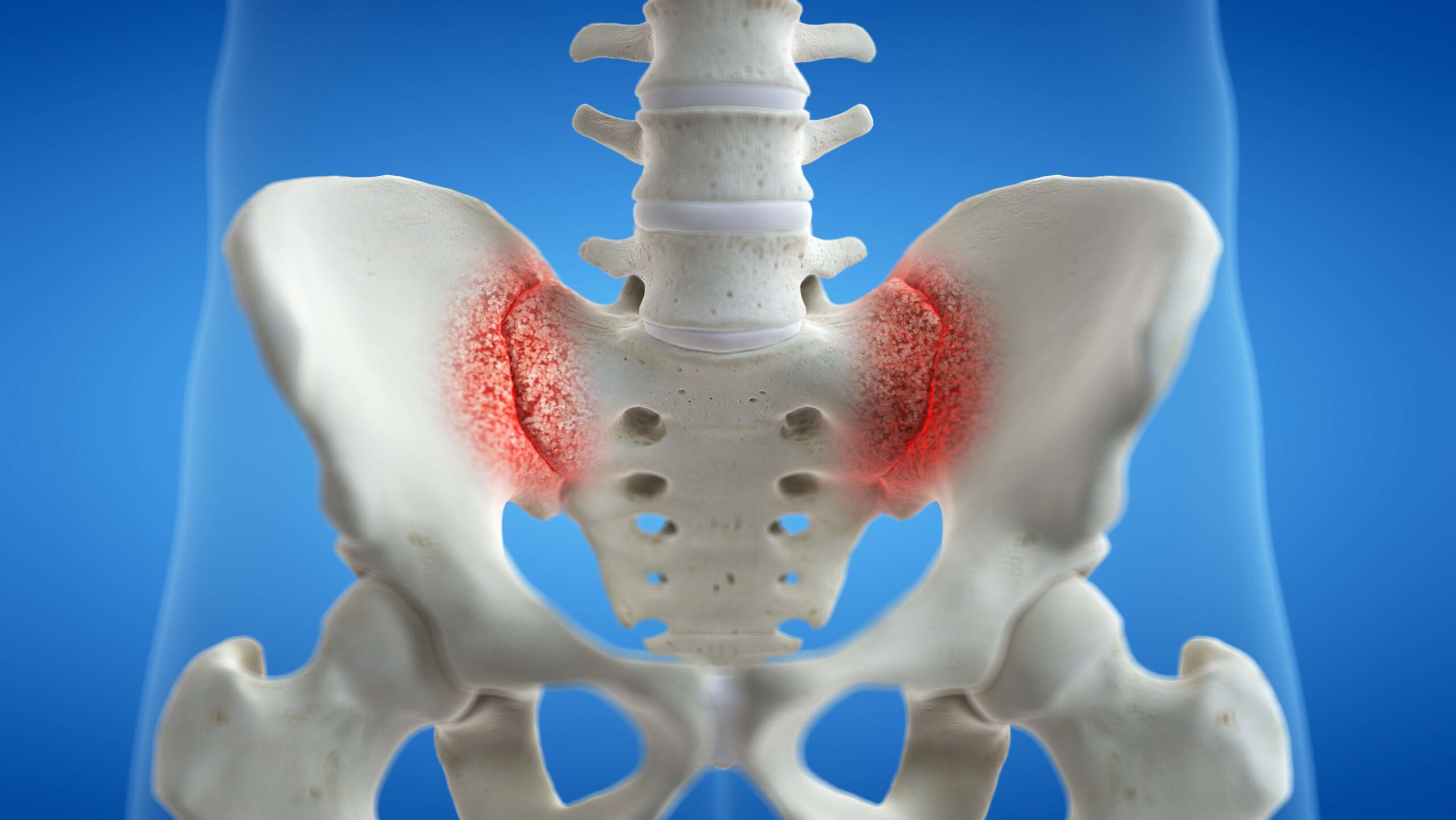

In this article we will discuss a common explanation for pain in these regions: the idea of a “rotated” or “misaligned” joint, typically the sacroiliac or “SI” joint located in the low back, but often referred to as the hip. We will illustrate why these ideas are wrong, and why the sacroiliac joints are far too stable to “slip,” “rotate,” or really move in a meaningfully harmful way.

Moving joints

First, a caveat: pregnancy represents a unique situation where there is increased laxity in many joints and ligaments as an adaptation to facilitate the eventual delivery of a fetus. This article is written for clinicians and non-pregnant people who have been told their hips or sacroiliac joints are “out of alignment”.

Prominent rehabilitation textbooks and continuing education courses often teach that the rotation of certain joints can cause hip and low back pain. This involves complex terminology like “rotated innominates”, “nutation”, and “counternutation”. [22] They also often claim that this rotation can be detected on physical examination and subsequently corrected to treat a person’s pain. Patients are sometimes told that their hip or sacroiliac joints are “out” or “misaligned”, and that they need to be put back into alignment.

The last decade reveals a large body of research that calls these claims into question. Careful research has found small degrees of movement in the sacroiliac joint; far below what any clinician’s physical examination could detect, particularly under several layers of superficial soft tissues. [1] Approximating movement in all 3 dimensions, a systematic review found 8 degrees of movement in the Z-axis, 2.2 degrees in the X-axis, and 4 degrees in the Y-axis. [2] The authors of that paper concluded:

“Motion in the [sacroiliac joint] is limited to minute amounts of rotation and translation, suggesting that clinical methods utilizing palpation of diagnosing [sacroiliac joint] pathology have limited utility.”

There are two points in that quote worth expanding upon, specifically relating to 1) the use of “palpation” (i.e., examination by touch), and 2) the diagnosis of sacroiliac joint pathology.

Research on the sacroiliac joint has found wide variation in joint structure and position among people. It has also found that healthcare professionals are generally poor at palpation. A study by Preece et al from 2008 found a side-to-side difference of up to 11 degrees in identifying pelvic landmarks, and up to 16 mm in hip bone positioning. [3] This study was in cadavers, so no inferences could be made on causation for pain in living humans, but finding 11 degrees of asymmetry when the joint itself has only been shown to move about 8 degrees calls into question our ability to use these landmarks to confidently identify a problem.

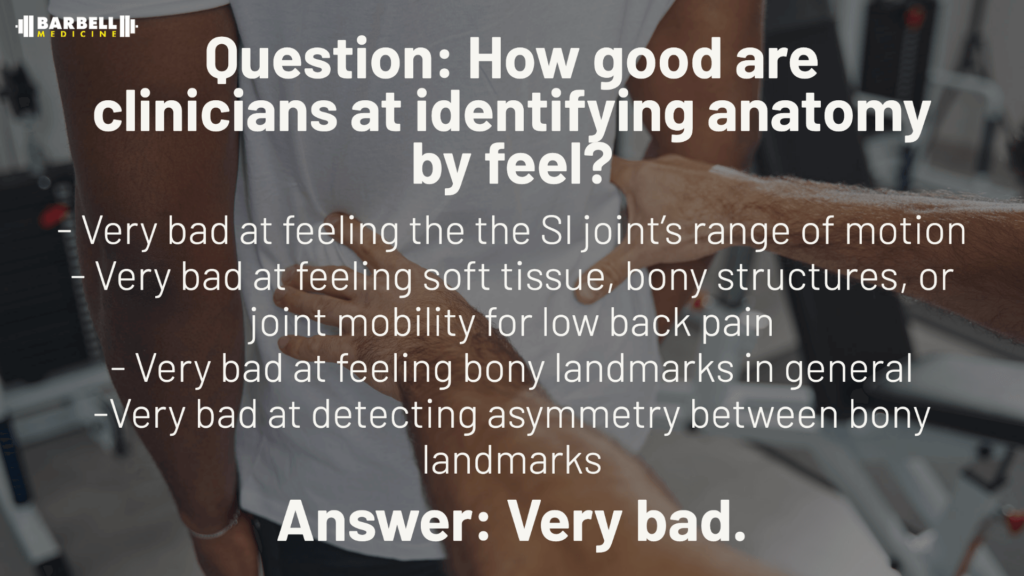

Even with this natural asymmetry, professionals have difficulty accurately identifying these basic landmarks at all. A 2007 study examined the reliability of palpation for assessing the SI joint. [4] They found a 48 percent agreement between evaluators, and a kappa statistic of -0.06. This essentially means clinicians could not agree at all on what they were finding with their hands-on examination. This is not unique to the sacroiliac joint, but is reflective of palpation in general as a recent systematic review found palpation of soft tissue “inconsistent,” and bony structures and joint mobility “poor.” [5]

Orthopedic Tests and Palpation

One of the main anatomic landmarks used for concerns about joint rotation is the posterior superior iliac spine (PSIS). This large landmark may appear useful, until recognizing that you can be on the landmark when palpating in many different places. Cooperstein and Hickey found a kappa statistic of 0.27 for clinicians palpating the PSIS, indicating a level of agreement between clinicians that falls far below that of any clinical utility. [6] Stovall and Kumar, in 2010, took this work a step further by examining the reliability of bony anatomic landmark asymmetry, and found multiple landmarks to possess poor reliability. [7]

If the joint itself is inherently stable, and we cannot accurately palpate even the largest landmarks, then we cannot confidently tell patients that “rotated hips” are the cause of their pain. Even if this were the case, there is nothing we can do about it using manual techniques. Tullberg et al. in 1998 evaluated what a manual technique does for position of the sacroiliac joint using Roentgen stereophotogrammeteric analysis. [8] They report being able to pick up less than 0.2 mm of translation along an axis using their technique. They found less than a millimeter of translation along any axis, and less than a degree of movement. Not only does this paper make a case against moving or resetting any joint with a manual technique, via its antiquity, it crushes the common argument that clinical practice is perpetually 10 years ahead of research evidence.

As for the orthopedic tests, most clinicians turn to Laslett’s 2008 paper on clusters of tests. [9] The author’s discussion section states:

“The manual therapy literature is awash with books, chapters, and papers on the treatment of the sacroiliac joint. Most of these treatment methods are based explicitly or implicitly on the presumption that some biomechanical malfunction or dysfunction causes either the SIJ or other tissues to provoke the pain of which the patient complains. This hypothesis is fragile indeed, since the means by which such dysfunctions are identified rest upon a flimsy evidential base, disputed by published data showing tests for SIJ dysfunction to be unreliable and invalid.”

Emphasis added.

There are also two studies looking at single-leg stance and a straight leg raise maneuver for detecting motion in the joint that find less than one degree of motion at the joint. [10, 11] Consequently, using a skill with low utility to identify movement that may be unrelated to pain to determine the correct technique and to detect changes in posterior pelvic position is questionable.

Now, for a quick dive into point two of the conclusions from Goode et al: that of diagnosing pelvic dysfunction. Part of the issue is the lack of a gold standard method to determine whether pain is originating from the SI joint. The paper by Laslett distinguishes between pelvic dysfunction and pelvic pain. There is no denying that a patient presenting with posterior pelvic pain is actually experiencing pain; what is more in question is how much, or whether the SI joint is the singular “pain generator” in the situation. The base rate of sacroiliac joint degeneration in the pain-free population has been estimated at 65% in one cohort, with about 30% presenting with “substantial degeneration.” [12] These are similar to the oft-cited study showing a high prevalence of herniated discs in the asymptomatic population by Brinjiki. [13]

If changes in pelvic morphology are so prevalent in the asymptomatic population, it is hard to confidently assign it as the root cause of a patient’s pain. So if our special physical exam tests lack validity, palpation is inaccurate and unreliable, and the joints themselves essentially do not move – what are we actually seeing in our patients? The answer is: likely whatever we were trained to see. Pareidolia is the psychological phenomenon by which we see or hear what we expect to see, even when no true signal exists. The classic examples are seeing a man on the moon or Jesus in a piece of toast. If we’re primed to see or hear a stimulus i.e. trained in school via esoteric diagrams of sacroiliac movements, many will see those movements whether they are present or not. Merckelback and Van de Ven’s 2001 study had undergraduate students listen to a recording and detect Bing Crosby’s ‘White Christmas’ in which approximately 30% of the students reported being able to hear the song.[14] As I’m sure the reader has inferred, there was no song in the noise. How many students, when learning “movement of the SI joint” were looking around in confusion as they were not able to palpate the movement? As the research shows, it turns out there was not any movement in the first place.

It also shows that when you do pick up a signal amongst the noise, it is nearly impossible to not see it again. Some things cannot be unseen. Take the picture below: do you notice anything interesting in it?

If not, you’re among the majority. Unlike the man on the moon or Jesus Christ toast, there is something in this picture staring right at you. There is a cow, staring directly at you. You’ll notice the face along the left side of the picture. Now that you have seen it, you will never be able to look at this picture as noise again. We’re hoping that the above presentation of evidence regarding the lack of movement of the SIJ will have the same effect.

All of this is to bring us to point 3.

Words Matter

Telling a patient that their hips are out of alignment, rotated, nutated, in line with Mercury while it is in retrograde, all have the same level of evidence: none. Yet, because of the normal information asymmetry between clinician and patient, they do not know that. To them, the clinician has given a problem (that does not exist) for which they do not have a solution (see prior parenthesis as to why). There has been near constant talk in the literature and on social media regarding the role of placebo and nocebo, and there is mounting evidence that clinicians unknowingly often have a nocebo effect. [15,16] Simply rewording an MRI has been shown to contribute a positive effect on patient’s perception of their condition. [17] Imagine the effect of rewording a clinical examination narrative eliminating fairytale problems like rotated hips or adhesions. This is why the argument has been made for a transition away from placebo and nocebo and towards contextual effects.[16, 18]

The more we gain insight into the subtleties of what we as clinicians are doing, the more we can harness the effects of therapeutic alliance and clinical equipoise. [19,20] Each of these factors, in their own right, can sway the outcome of a treatment. Therapeutic alliance is the relationship formed between the healthcare provider and the patient, or getting to be on the same team. Just like a coach cannot be on the field influencing the game, the role of the provider should be encouragement, not a constant narrative of negatives. The coach is not allowed to step on the field to intervene with the game. With the amount of coaches/rehab specialists on social media offering ways to “fix hips” or posting videos of moving a hip model with rubber bands for joints you would think the “game” is only played by them, and not those experiencing pain.

A clinician’s belief that a treatment is going to work has itself been shown to influence outcomes, even if the intervention is inert. [21] How much of the current effect of interventions based on the narrative of hips being out of alignment is based on such belief is hard to say, but it certainly plays a role. We cannot continue to support the positive belief that our interventions are working at the expense of instilling a negative belief in patients that there is something wrong with them. This is all predicated upon the narrative attached to the diagnosis, prognosis, and intervention. The diagnosis, from the perspective of the contribution of the SI joint to pain should not include the narrative of hips rotating or being out of alignment as that is entirely unsupported in the literature. The prognosis should serve as a positive reminder to patients that they are likely going to get better, and they are ultimately in control of their situation. The narrative of the intervention should not include an immediate changing of local tissue structure. Patients should not feel they need us to fix them. We are ultimately facilitators, not mechanics. Our job, like that of a coach, should be to guide the path, not play the game.

Take-home Points

- The ilium and sacrum do not move on a perceptible level

- The tests we have to determine movement likely rely on pareidolia

- Words have a lasting meaning of patient’s perception of their situation

References:

- Nagamoto et al. Sacroiliac joint motion in patients with degenerative lumbar spine disorders. J Neurosurg Spine. 2015;23(August):209-216. doi:10.3171/2014.12.SPINE14590.

- Goode A, Hegedus EJ, Sizer P, Brismee J-M, Linberg A, Cook CE. Three-dimensional movements of the sacroiliac joint: a systematic review of the literature and assessment of clinical utility. J Man Manip Ther. 2008;16(1):25-38. doi:10.1179/106698108790818639.

- Preece SJ, Willan P, Nester CJ, Graham-Smith P, Herrington L, Bowker P. Variation in Pelvic Morphology May Prevent the Identification of Anterior Pelvic Tilt. J Man Manip Ther. 2008;16(2):113-117. doi:10.1179/106698108790818459.

- Robinson HS, Brox JI, Robinson R, Bjelland E, Solem S, Telje T. The reliability of selected motion- and pain provocation tests for the sacroiliac joint. Man Ther. 2007;12(1):72-79. doi:10.1016/j.math.2005.09.004.

- Nolet PS, Yu H, Côté P, Meyer AL, Kristman VL, Sutton D, Murnaghan K, Lemeunier N. Reliability and validity of manual palpation for the assessment of patients with low back pain: a systematic and critical review. Chiropr Man Therap. 2021 Aug 26;29(1):33.

- Cooperstein R, Hickey M. The reliability of palpating the posterior superior iliac spine: a systematic review. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2016;60(1):36-46.

- Stovall BA, Kumar S. Anatomical Landmark Asymmetry Assessment in the Lumbar Spine and Pelvis: A Review of Reliability. PM R. 2010;2(1):48-56. doi:10.1016/j.pmrj.2009.11.001.

- Tullberg T, Blomberg S, Branth B, Johnsson R. Manipulation does not alter the position of the sacroiliac joint: A roentgen stereophotogrammetric analysis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1998;23(10):1124-1129. doi:10.1097/00007632-199805150-00010.

- Laslett M. Evidence-Based Diagnosis and Treatment of the Painful Sacroiliac Joint. Man Ther. 2009;13(3):124.

- Kibsgård TJ, Røise O, Sturesson B, Röhrl SM, Stuge B. Radiosteriometric analysis of movement in the sacroiliac joint during a single-leg stance in patients with long-lasting pelvic girdle pain. Clin Biomech. 2014;29(4):406-411. doi:10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2014.02.002.

- Kibsgård TJ, Röhrl SM, Røise O, Sturesson B, Stuge B. Movement of the sacroiliac joint during the Active Straight Leg Raise test in patients with long-lasting severe sacroiliac joint pain. Clin Biomech. 2017;47(May 2017):40-45. doi:10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2017.05.014.

- Eno J-JT, Boone CR, Bellino MJ, Bishop JA. The Prevalence of Sacroiliac Joint Degeneration in Asymptomatic Adults. doi:10.2106/JBJS.N.01101.

- W. Brinjikji, P.H. Luetmer BC. Systematic Literature Review of Imaging Features of Spinal Degeneration in Asymptomatic Population. AJNR Neuroradiol. 2015;36(4):811-816. doi:10.3174/ajnr.A4173.Systematic.

- Merckelbach H, Van de Ven V. Another White Christmas: Fantasy proneness and reports of “hallucinatory experiences” in undergraduate students. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2001;32(3):137-144. doi:10.1016/S0005-7916(01)00029-5.

- Setchell J, Costa N, Ferreira M, Makovey J, Nielsen M, Hodges PW. Individuals’ explanations for their persistent or recurrent low back pain: a cross-sectional survey. doi:10.1186/s12891-017-1831-7.

- Testa M, Rossettini G. Enhance placebo, avoid nocebo: How contextual factors affect physiotherapy outcomes. Man Ther. 2016. doi:10.1016/j.math.2016.04.006.

- Bossen JKJ, Hageman MGJS, King JD, Ring DC. Does rewording MRI reports improve patient understanding and emotional response to a clinical report? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013. doi:10.1007/s11999-013-3100-x.

- Rossettini G, Carlino E, Testa M. Clinical relevance of contextual factors as triggers of placebo and nocebo effects in musculoskeletal pain. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2018;19:27. doi:10.1186/s12891-018-1943-8.

- Bishop MD, Bialosky JE, Penza CW, Beneciuk JM, Alappattu MJ. The influence of clinical equipoise and patient preferences on outcomes of conservative manual interventions for spinal pain: An experimental study. J Pain Res. 2017;10:965-972. doi:10.2147/JPR.S130931.

- Ferreira PH, Ferreira ML, Maher CG, Refshauge KM, Latimer J, Adams RD. The Therapeutic Alliance Between Clinicians and Patients Predicts Outcome in Chronic Low Back Pain.

- Cook C, Sheets C. Clinical equipoise and personal equipoise: two necessary ingredients for reducing bias in manual therapy trials. J Man Manip Ther. 2011;19(1):55-57. doi:10.1179/106698111X12899036752014.

- Dutton, M. (2023). Dutton’s Orthopaedic Examination, Evaluation, and intervention. McGraw Hill.