Headaches are a common, painful, and oftentimes disabling symptom that can pop-up at rest, during exercise or the times between. In this article, we’ll discuss headaches that occur during exercise and how exercise can help reduce headache frequency.

Headaches can be divided into “primary” or “secondary” types. Primary headaches are those that do not have a clear identifiable cause, and include tension-type, migraine, cluster headaches. In contrast, secondary headaches are clearly attributable to an underlying medical condition, such as a headache resulting from trauma, brain tumors, or infections, among many other things.

Headaches that occur during or immediately after exercise without any attributable cause are called primary exercise headaches (PEH). Primary exercise headaches tend to occur in younger people, and are slightly more common in women than men. [1] While their exact cause is unknown, risk factors include hot weather, high altitude, and/or sustained strenuous activity. [2]

New headaches during exercise should be evaluated by a physician, with current guidelines recommending brain imaging with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA), or computed tomography (CT) and CT angiography (CTA), to rule out problems with the structures in the brain and its blood vessels..

Fortunately, PEH is relatively rare compared to other headache syndromes such as migraines. Migraines are an episodic disorder that typically produce a one-sided throbbing headache lasting several hours to several days. They affect 12-15% of adults worldwide, and are the most common diagnosis among patients seeing their primary care doctor for headache. Migraines are a major cause of disability and reduced quality of life, ranking second only to low back pain globally. [3]

People who get PEH may also have migraines outside of exercise, though most primary exercise headaches do not involve typical migraine symptoms like nausea, vomiting, sensitivity to light and/or sound, and pain on one side of the head. [1,4] Some people report that exercise is a trigger for their migraines that the pain gets worse upon initiating exercise, often causing them to avoid exercise. [5, 6, 7]

There’s limited data on how frequently exercise is a trigger for migraine headaches, but the largest dataset, a prospective trial on 1207 patients between the ages of 13 and 80 years old, found that exercise was reported to be a trigger in 22% of subjects. [8] Despite this, regular exercise actually tends to help reduce migraine frequency.

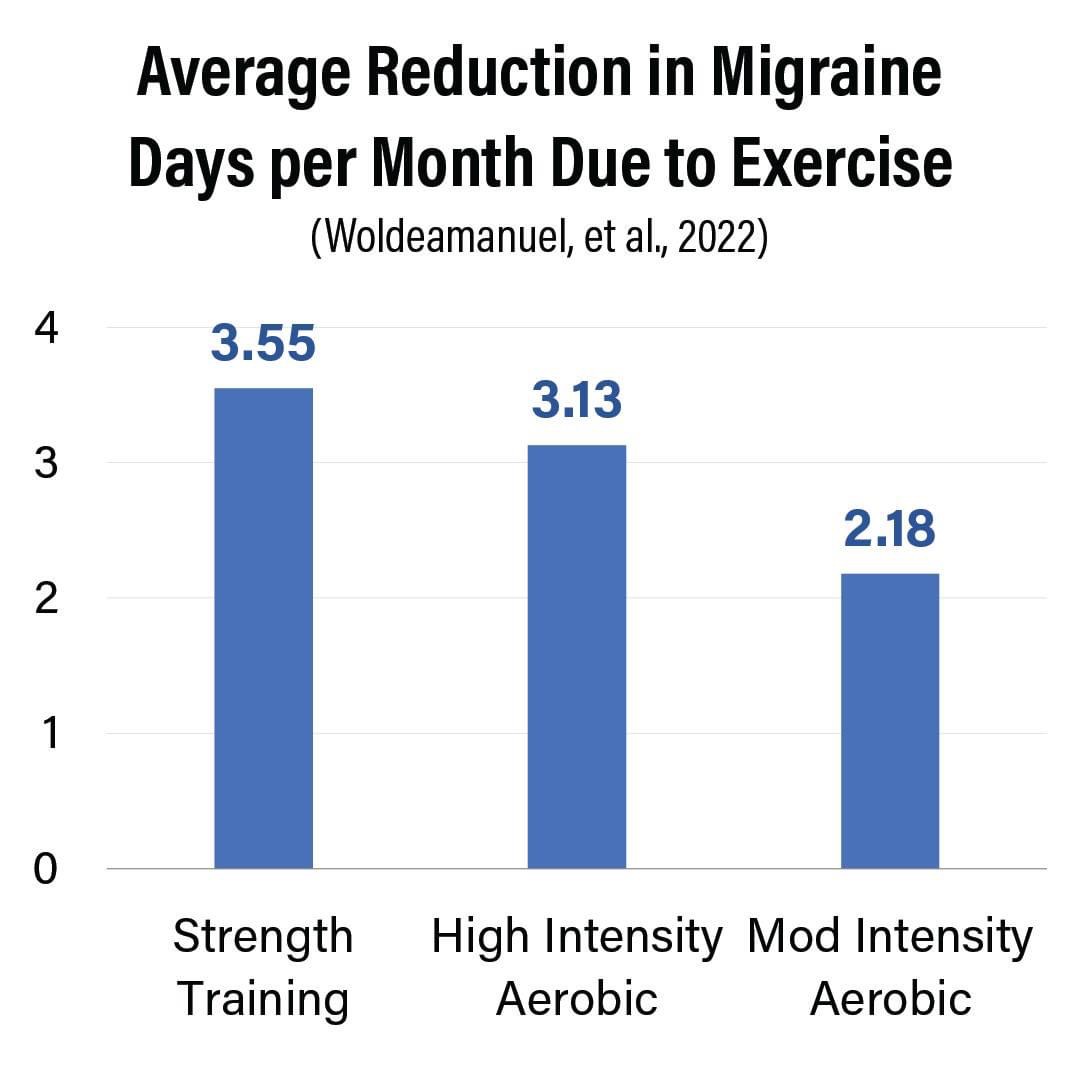

Two case studies have reported successful abortion of a migraine with exercise. [9,10] More recently, a 2022 systematic review and network meta-analysis examined 21 controlled trials of interventions for the prevention of migraine. The authors found that all exercise interventions were effective for reducing the frequency of migraine. [11]

This is most likely due to an altered migraine triggering threshold in people who exercise regularly. However, the frequency and intensity of exercise that is required is still an open question, which should be addressed in future studies to delineate an evidence-based exercise program to prevent migraine in sufferers.

Regular participation in exercise has also shown benefits for conditions that commonly co-occur with migraine and other headache disorders such as depression, anxiety, sleep disturbances, and self-image issues. [5]

Overall, it appears that exercise may be useful for not only reducing migraine frequency in many, but also for improving nearly every aspect of general health in the population. Individuals who frequently experience the onset of headache during exercise should work with their physician to make sure there isn’t an underlying medical cause. Barring an underlying medical condition that makes exercise unsafe for a person until it is treated, we recommend that all individuals, including those with headache disorders, meet or exceed the current physical activity guidelines.

Check out the discussion I had with Dr. Baraki about the emerging research regarding strength training and health:

References:

- Sjaastad O, Bakketeig LS. Exertional headache–II. Clinical features Vågå study of headache epidemiology. Cephalalgia. 2003 Oct;23(8):803-7. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.2003.00588.x. PMID: 14510926.

- Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS). The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (beta version). Cephalalgia. 2013 Jul;33(9):629-808. doi: 10.1177/0333102413485658. PMID: 23771276.

- Ashina M, Katsarava Z, Do TP, Buse DC, Pozo-Rosich P, Özge A, Krymchantowski AV, Lebedeva ER, Ravishankar K, Yu S, Sacco S, Ashina S, Younis S, Steiner TJ, Lipton RB. Migraine: epidemiology and systems of care. Lancet. 2021 Apr 17;397(10283):1485-1495. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32160-7. Epub 2021 Mar 25. PMID: 33773613.

- Hanashiro S, Takazawa T, Kawase Y, Ikeda K. Prevalence and clinical hallmarks of primary exercise headache in middle-aged Japanese on health check-up. Intern Med. 2015;54(20):2577-81. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.54.4926. Epub 2015 Oct 15. PMID: 26466691.

- Irby MB, Bond DS, Lipton RB, Nicklas B, Houle TT, Penzien DB. Aerobic Exercise for Reducing Migraine Burden: Mechanisms, Markers, and Models of Change Processes. Headache. 2016 Feb;56(2):357-69. doi: 10.1111/head.12738. Epub 2015 Dec 8. PMID: 26643584; PMCID: PMC4813301.

- Nadelson C. Sport and exercise-induced migraines. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2006 Feb;5(1):29-33. doi: 10.1097/01.csmr.0000306516.25172.21. PMID: 16483514.

- Martins IP, Gouveia RG, Parreira E. Kinesiophobia in migraine. J Pain. 2006 Jun;7(6):445-51. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2006.01.449. PMID: 16750801.

- Kelman L. The triggers or precipitants of the acute migraine attack. Cephalalgia. 2007 May;27(5):394-402. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2007.01303.x. Epub 2007 Mar 30. PMID: 17403039.

- Darling M. The use of exercise as a method of aborting migraine. Headache. 1991 Oct;31(9):616-8. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.1991.hed3109616.x. PMID: 1774180.

- Strelniker YM. Intensive running completely removes a migraine attack. Med Hypotheses. 2009 May;72(5):608. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2009.01.004. Epub 2009 Feb 10. PMID: 19211193.

- Woldeamanuel YW, Oliveira ABD. What is the efficacy of aerobic exercise versus strength training in the treatment of migraine? A systematic review and network meta-analysis of clinical trials. J Headache Pain. 2022 Oct 13;23(1):134. doi: 10.1186/s10194-022-01503-y. PMID: 36229774; PMCID: PMC9563744.