In 2019 we published our Beginner Prescription, a free workout program with supporting materials designed to answer the question, “Where do I start with exercise to improve my health?” However, the program did require access to gym equipment, and we understand that this can be a barrier to engaging exercise for a variety of reasons, such as access to a gym, cost, travel, fear/anxiety, or even a viral pandemic.

Part of our mission here at Barbell Medicine is to empower folks to take charge of their health by providing high-quality resources. With that in mind, we wanted to expand our Beginner Prescription to include at-home training options that require little to no equipment, thus making it easier for individuals to exercise! For individuals interested in an expanded resource with additional workouts, check out the full version of the At-Home Training Template.

Introduction

Physical inactivity is a major health problem worldwide and is the fourth leading global risk factor for death according to the World Health Organization (WHO), behind high blood pressure, tobacco use, and elevated blood sugar (WHO 2009). In fact, only ~20% of the US population report meeting current exercise recommendations (Piercy 2018). However, this number is likely to be much lower, as when activity levels are directly measured, less than 10% of adults actually meet these guidelines (Zenko 2019).

Fortunately, even small changes have measurable positive effects. For example, walking just 2,000 more steps per day (about 20 minutes of brisk walking) lower the risk of having a cardiovascular event like heart attack or stroke by 10%, and lowers the risk of blood sugar problems by 25% (Yates 2014 Ponsonby 2011), and these benefits increase further with more activity.

Similarly, strength training 2-3 times per week is associated with a 23% lower risk of death from all causes, as compared to those who only do aerobic exercise (Dankel 2016). For more background information about exercise, health, and our general recommendations, check out these two articles: The Beginner Prescription and Where Should My Priorities Be to Improve My Health?.

With this in mind, we’d love to get more individuals meeting or exceeding the 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, which are as follows:

- 150 to 300 minutes per week of moderate-intensity aerobic physical activity, OR;

- 75 to 150 minutes per week of vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity, AND;

- Resistance training of moderate or greater intensity involving all major muscle groups on 2 or more days per week.

For clarity, a combination of both vigorous and moderate-intensity aerobic activity can be used to meet activity targets. Additionally, intensity levels are described in the units Metabolic Equivalent of Task, or MET. One MET is how much energy is used while at rest, whereas a 4 MET activity requires four times the energy used by the body at rest.

“Moderate-intensity” activities are defined as 3-5.9 METs, e.g. walking at 3 miles per hour (3.3 METs), heavy gardening (4 METs), or cycling at 10 miles per hour (4 METs).

“Vigorous-intensity” activity is defined as 6 METs or greater, e.g. strenuous hiking (6 METs), running at 6 miles per hour (10 METs), or aerobic calisthenics (6-10 METs).

These guidelines are suitable for nearly all individuals who do not have a specific medical reason to reduce or avoid physical activity such as a serious, uncontrolled or unstable medical/surgical condition that requires urgent attention.

Individuals who have mild, short-term illnesses such as a cold, sinus infection, or musculoskeletal pain should aim to remain physically active assuming that they aren’t exposing others to infectious risk. This should not be an issue for an at-home workout program. Similarly, we would also recommend that individuals with adequately-controlled, stable chronic medical conditions such as autoimmune diseases, heart disease, high blood pressure, persistent pain, etc. meet or exceed these guidelines as well.

In the overwhelming majority of situations, the benefits of exercise far outweigh the potential risks. If you’re unsure if it’s okay to exercise, we would recommend taking the following questionnaire to see if you need to talk to your doctor prior to starting an exercise program. If you answered yes to any of the items in the linked questionnaire, contact your physician for guidance. They may benefit from using this screening form to assess your individual situation as well.

Program Goals

This program is aimed at individuals desiring an option to exercise at home or other situations where they don’t have access to a gym. It should be stated that this program is not designed to maximize 1-Rep-Max (1RM) strength, muscular hypertrophy, or athletic development, as these goals tend to require access to more training equipment, e.g. a barbell or other equipment specific to the goal.

On the other hand, we think that we can meet or exceed the current guideline recommendations for both strength and aerobic training without access to a gym. From a health-focused perspective, we are specifically aiming to improve the following outcomes using this program:

Physical Strength – Strength is force production that is measured in a specific context. In other words, both a 1-repetition max effort and a maximum set of push-ups are tests of strength, though they require different adaptations to demonstrate an improvement in performance. Given the equipment limitations of this program, it is unlikely that an experienced lifter will improve their 1RM squat performance if they’re using this program and not performing any heavy squats with a barbell. Conversely, it is likely that an experienced individual will be able to maintain a significant amount of strength by using this program, especially for short periods of time, e.g. less than 3 weeks (McMaster 2013). Finally, individuals who are less experienced will likely improve their strength potential across different exercises on this program, though they will need to transfer this potential to specific tasks (e.g. back squats or deadlifts) via training those specific lifts.

Lean Body Mass – Lean body mass refers to all “non-fat” mass in the human body, e.g. muscle, water, bone, and organ tissue. Increases in muscle mass (and its contents) represent the majority of increases in lean tissue from exercise via a process termed hypertrophy. There are three major determinants for muscular hypertrophy: 1) motor unit recruitment, 2) range of motion, and 3) volume of exercise. Fortunately, all three criteria can be met using an at-home workout, though this isn’t meant to suggest that there are no benefits to going to a gym to have access to additional equipment. Nevertheless, lean body mass may improve in untrained and trained individuals alike using this program

Cardiorespiratory Fitness – Cardiorespiratory fitness, aerobic fitness, or “cardio”, is defined as the ability to sustain an activity at a particular pace. Increased levels of cardiorespiratory fitness are associated with improvements in health such as reducing the risk of excess body fat, cardiovascular disease (e.g., heart attacks and strokes), cognitive decline, and premature death in general. Additionally, improving an individual’s conditioning tends to improve their work capacity, training workload tolerance, and their performance in physical tasks that challenge their endurance. These programs use a variety of different elements, e.g. circuits and high-intensity interval training to develop cardiorespiratory fitness

Program Structure

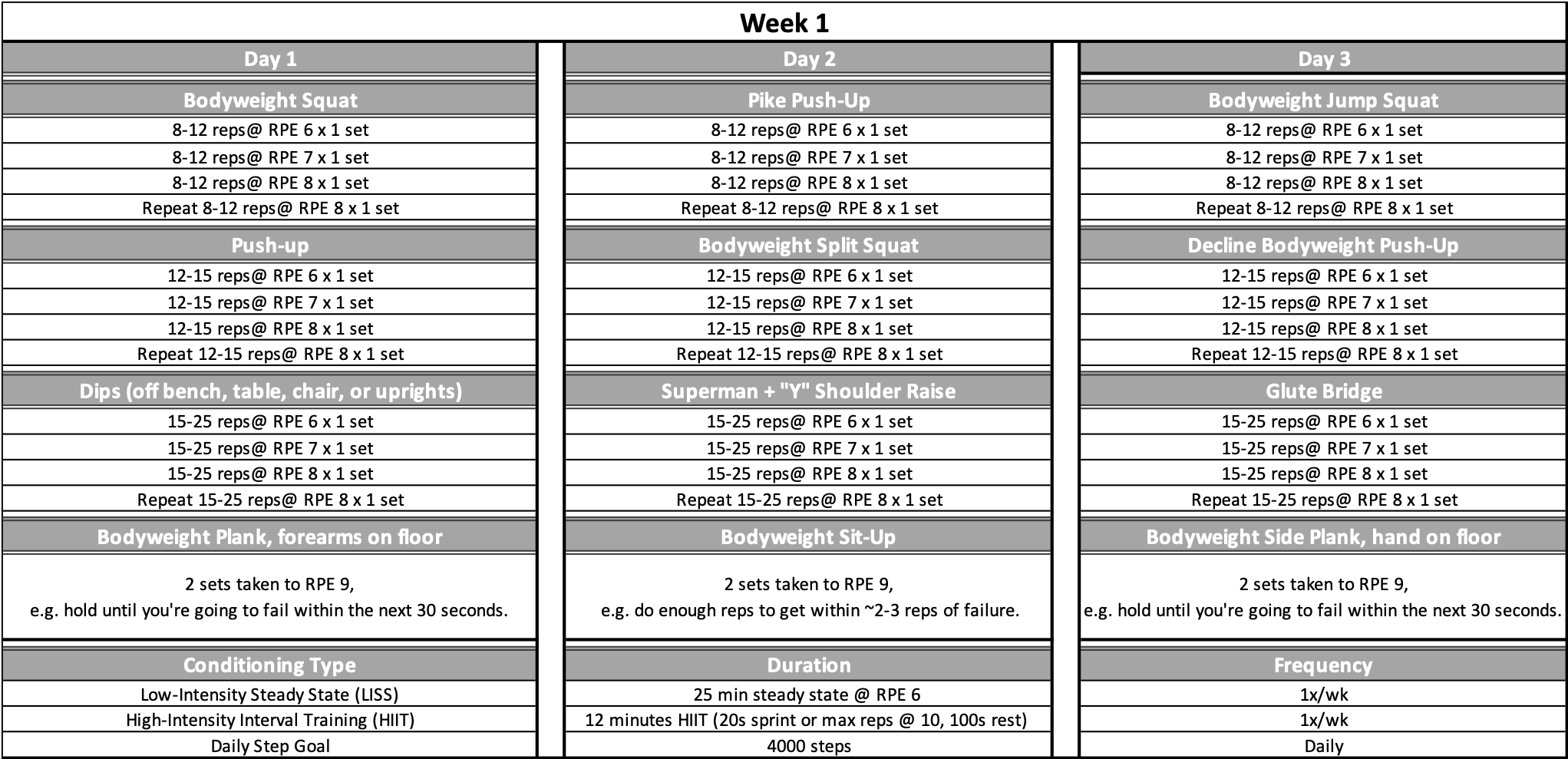

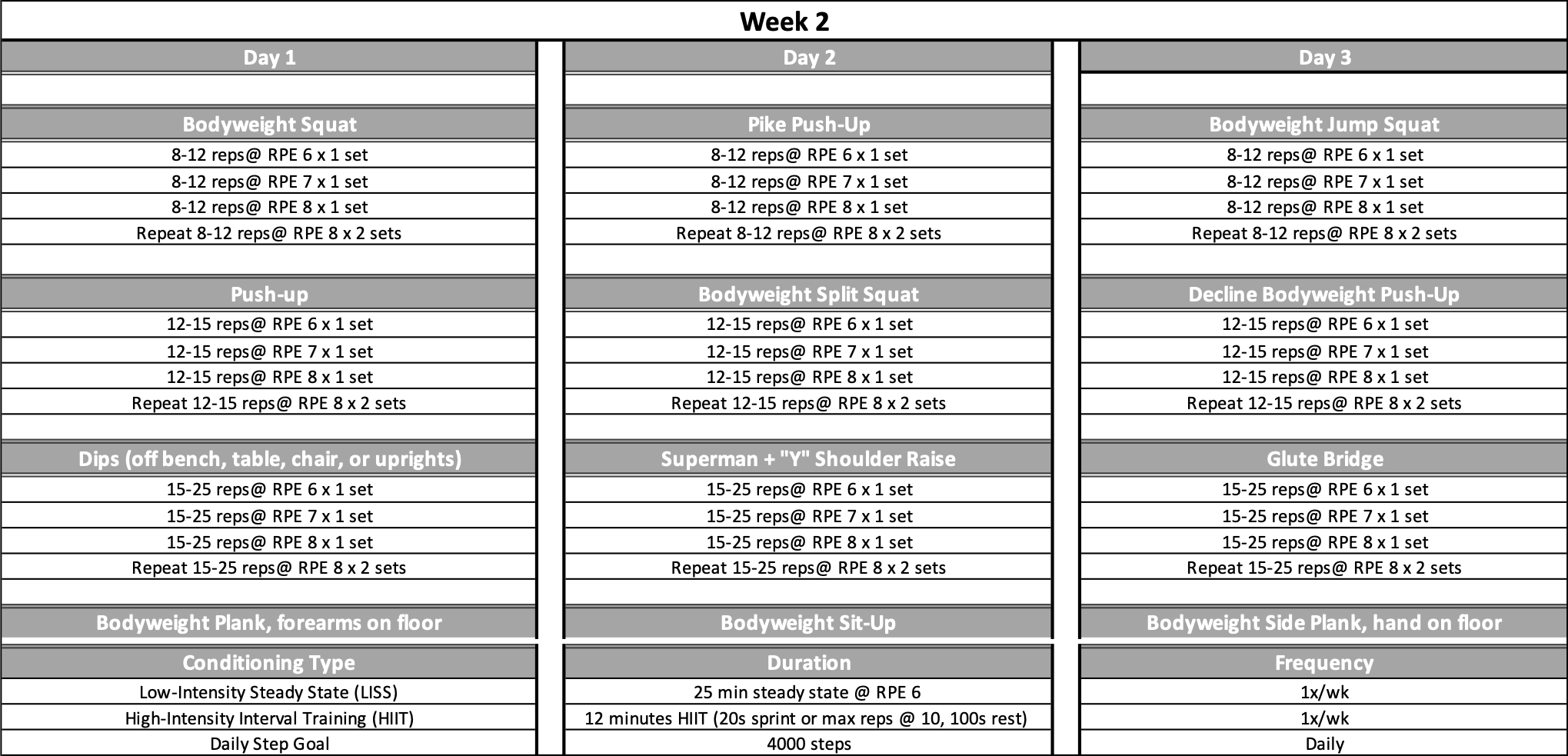

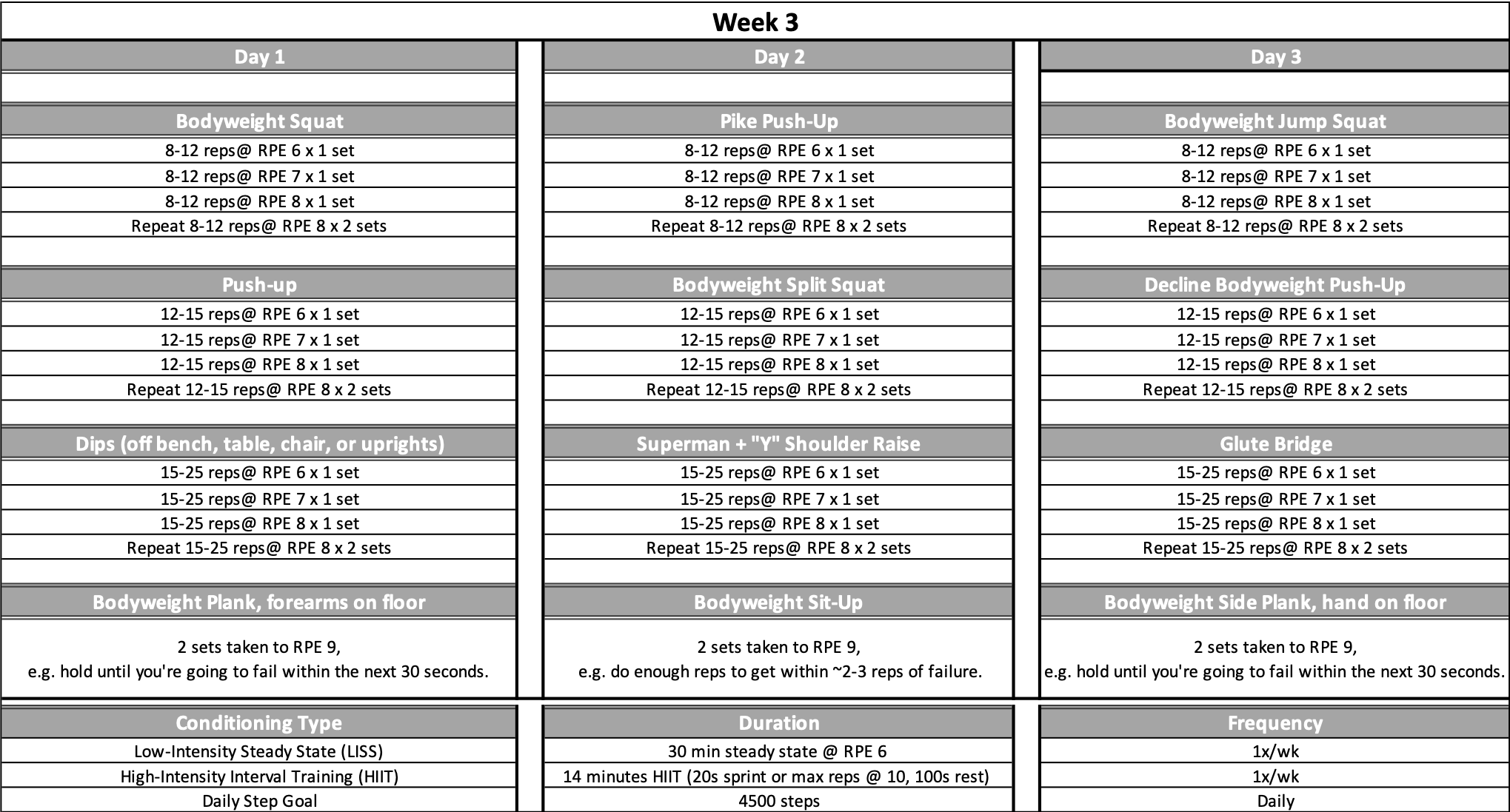

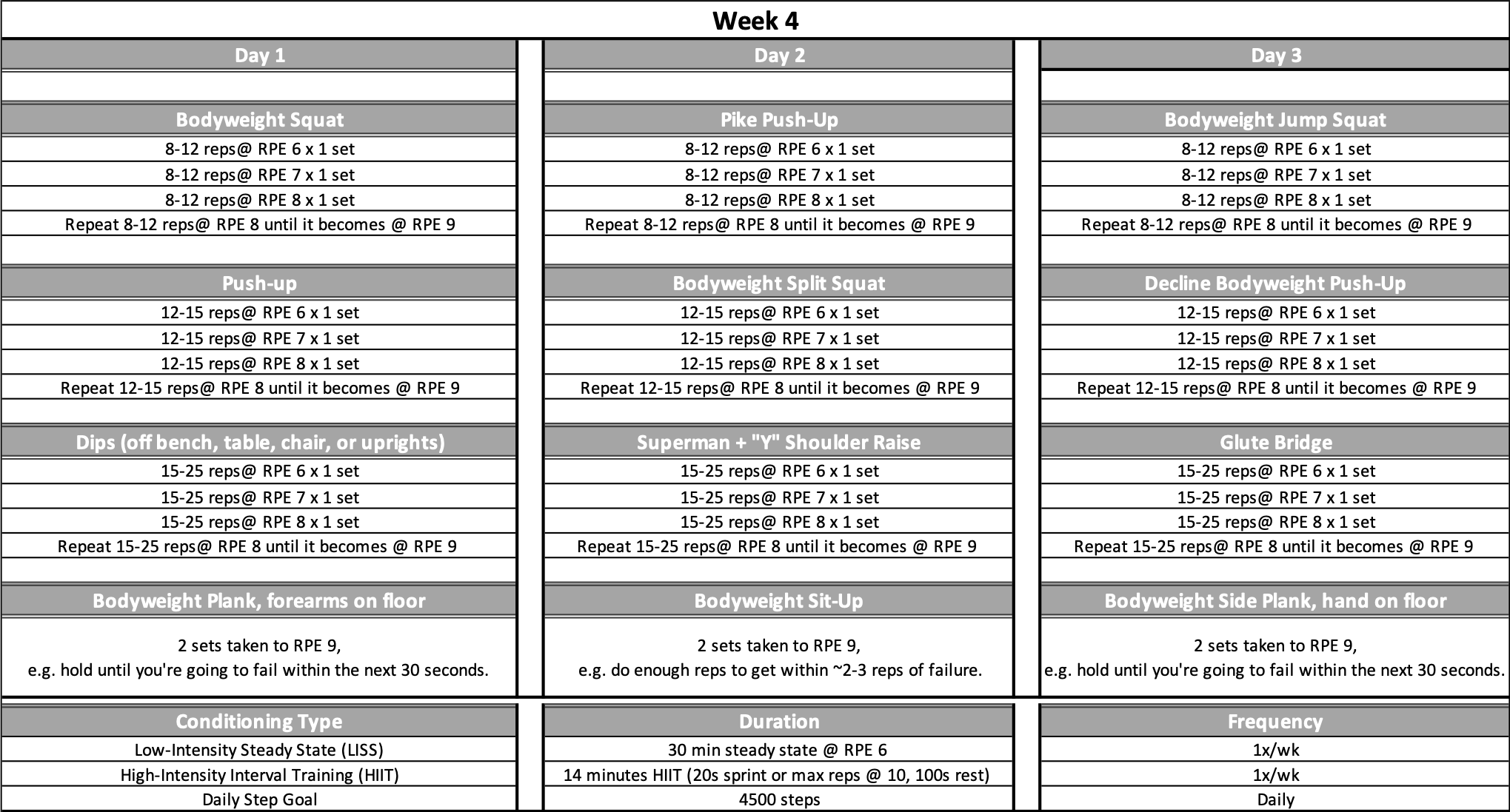

The program is 4 weeks long and includes 3 days of strength training per week and 3 days of conditioning. After 4 weeks it is reasonable to continue using the template for an extended period of time if an individual is continuing to see results. Ideally, strength training workouts are completed on non-consecutive days and the conditioning workouts are completed on the days in between, for example:

- Day 1 (Monday): Strength Training

- Day 2 (Tuesday): Conditioning

- Day 3 (Wednesday): Strength Training

- Day 4 (Thursday): Conditioning

- Day 5 (Friday): Strength Training

- Day 6 (Saturday): Conditioning

- Day 7 (Sunday): Off

Our preference is for individuals to be active on most days of the week, although completing all (or some) the prescribed work in a manner that you can adhere to is more important. With that in mind, strength training and conditioning may be done on the same day if you prefer.

The Program

In order to make strength training more accessible to the general population, the full version of the At-Home Training Template includes two 8-Week templates that allow users to select their own exercises from a list of options based on personal preferences, goals, and equipment availability.

In the version presented here we will provide “defaults” that assume the individual is relatively new to strength training and doesn’t have access to any equipment. For individuals with access to equipment or who have a more extensive training history, see the exercise selection section that follows the template.

NOTE: if an individual’s starting level of fitness is below that required to accomplish this program, changes should be made to based on individual abilities. For example, someone who can’t perform a bodyweight squat might squat to a chair; someone who can’t perform a push-up may perform a steep incline push-up off of a table or countertop. Repetition ranges may also be scaled down based on abilities as well, as long as target effort levels are reached.

Exercise Selection

The main focus when selecting exercises should be on selecting a movement that allows you to get close to muscular failure with the equipment available to you. Practically speaking, this means getting to within about 5 repetitions of muscular failure for most dynamic exercises or 20-30 seconds of failure for isometric exercises. “Muscular failure” here means the point at which you could no longer perform another repetition, or are unable to hold an isometric position any longer.

“Dynamic” exercises include a concentric phase where the muscle shortens (the upward phase) while producing force and/or an eccentric phase where the muscle lengthens (the “downward” phase) while producing force. In contrast, “isometric” exercises like a wall-sit, plank, or similar do not have either of these phases, as the muscle maintains the same length while producing force.

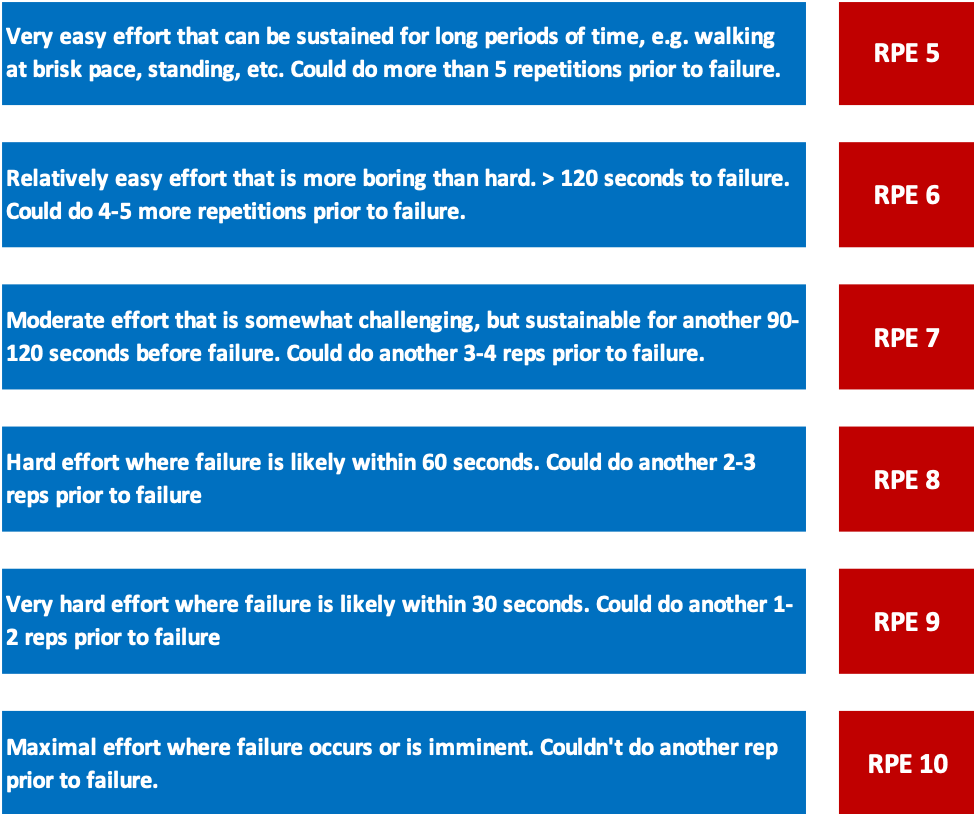

In order to gauge how close you are to failure on a particular exercise and rep range, we recommend using a Rating of Perceived Exertion, or RPE. The full text accompanying the At-Home Template contains a more thorough discussion of RPE and a step-by-step guide on how to apply it to select exercises, load, and warm-ups for each exercise. For a quick explanation, see the following videos created by Barbell Medicine staff coach Alan Thrall, understanding that the same principles carry over from barbell training to bodyweight exercises.

We recommend using the following chart to help determine your RPE:

We understand that introducing this concept to guide loading can be challenging or intimidating for someone new to exerciser. However, our experience and the current research suggest that most individuals can effectively choose their exercises, repetitions, and/or loads to match a targeted level of exertion within a few weeks to a usable level of accuracy. For some trainees, this may happen much sooner whereas others may take a bit longer, which is okay, especially over a (hopefully) lifelong training career.

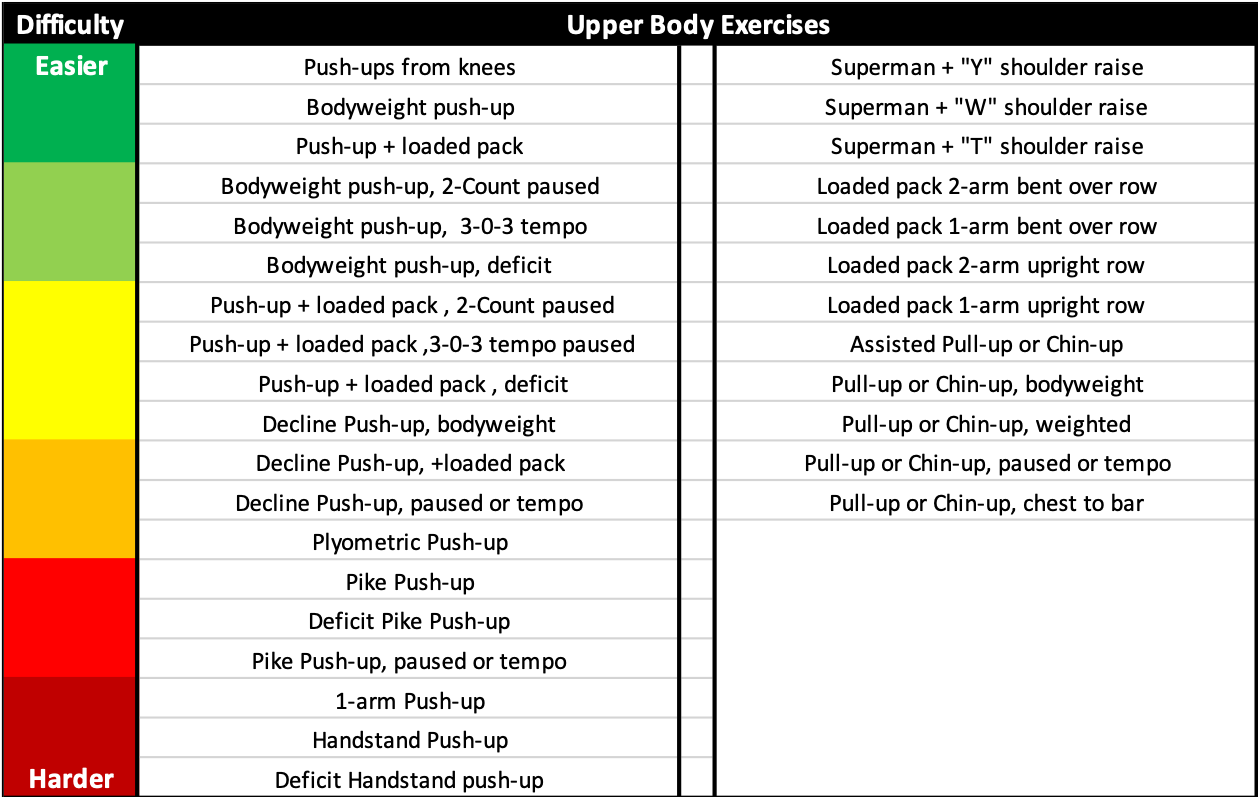

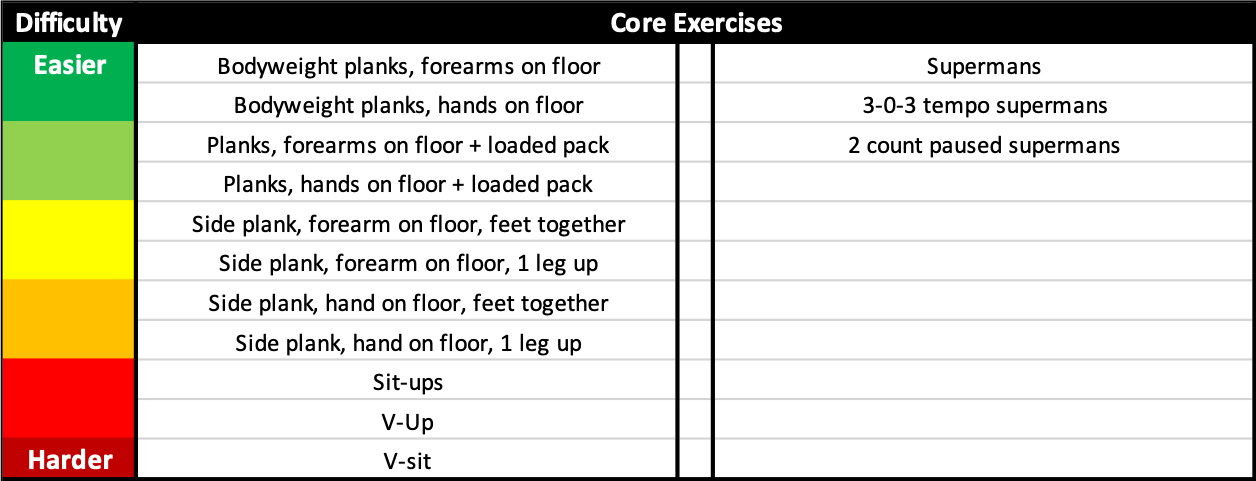

Getting close to muscular failure ensures that the majority of the muscle fibers are being recruited to produce force, which tends to promote greater fitness adaptations like increases in lean body mass and most types of strength. Therefore, we recommend you pick exercises that are likely to get you close to failure for the prescribed repetition ranges. For most movement patterns we provide variations that increase the load, range of motion, alter the tempo, include a plyometric concentric component, add a pause in a mechanically disadvantageous portion of an exercise, or make the exercise unilateral.

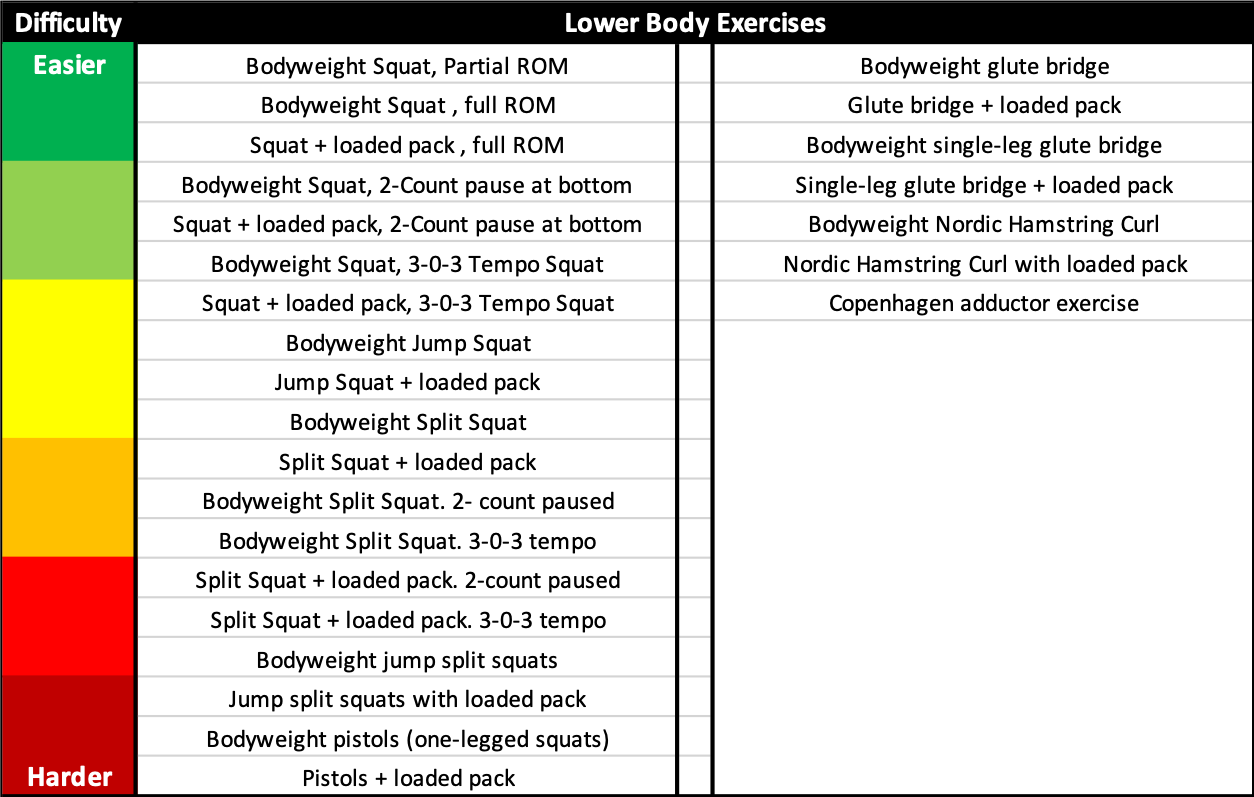

While there are many inter-individual differences on how difficult an exercise is, we can provide some general guidance in exercise selection for each of the major movement types in the pictures below.

As you can see, there are many ways to alter an exercise to get an individual closer to muscular failure. The exercise slots are such that we want to get within 2-3 reps of failure (e.g. RPE 8) in the following repetition ranges:

- Exercise 1: 8-12 repetitions

- Exercise 2: 12-15 repetitions

- Exercise 3: 15-25 repetitions

Let’s work through an example. Imagine an individual is trying to pick a lower body exercise that gets them to RPE 8 within the 8-12 repetition range. Bodyweight-only squats with a full range of motion are way too easy for them, as doing 12 repetitions isn’t even an RPE 5 for them. In this case, we’d recommend trying to add load, e.g. a backpack stuffed with some water bottles, books, etc.; or, if that’s not available, switching to a unilateral exercise such as a split squat. If that’s still too easy, we’d recommend going further down the difficulty scale towards a one-legged squat or even one-legged squat with a 2-count pause. In any case, most individuals should be able to find a variation that gets them to the appropriate RPE prescription for a given rep range.

Warm-Up

For the warm-up, we recommend performing multiple sets of the specific exercise with gradually increasing intensity. For example, if someone is trying to do work up to a RPE 8 set of 12-15 repetitions on squat with loaded backpack, we’d advise something like this:

- Bodyweight Squat x 5 reps x 3-5 sets

- Squat + loaded pack x 12 reps x 1 set with 10lbs (RPE <6)

- Squat + loaded pack x 12 reps x 1 set with 25lbs (RPE <6)

- Squat + loaded pack x 12 reps x 1 set with 40lbs (RPE ~7)

- Squat + loaded pack x 12 -15 reps x 1 set with 50lbs (RPE 8 – target achieved!)

- We’d recommend 2-3 minutes of rest in between sets.

For an individual who either prefers bodyweight-only variations or who doesn’t have access to any external resistance, e.g. dumbbells, backpacks, etc., we’d recommend working up to the target intensity and rep prescription, e.g. 12-15 reps @ RPE 8 for the split squat, via something like this:

- Bodyweight Squat x 5 reps x 3-5 sets

- Bodyweight Split Squat x 5 reps x 1 set (RPE <6)

- Bodyweight Split Squat x 8 reps x 1 set (RPE <6)

- Bodyweight Split Squat x 10 reps x 1 set (RPE ~7)

- Bodyweight Split Squat x 15 reps x 1 set (RPE 8 – target achieved!)

- We’d recommend 2-3 minutes of rest in between sets.

If you happen to overshoot and end up either skipping a set (e.g. your planned RPE 7 feels like RPE 9) or needing an extra warm-up set, that’s okay! Don’t worry about it, just move on with the rest of your workout.

Conditioning

For conditioning, we often use both high-intensity interval training (HIIT) and low-intensity “steady state” (LISS) work, as we think both are important for health and performance. However, we emphasize adherence to regular exercise much more than following an exact prescription. Therefore, if someone prefers to do exclusively LISS or HIIT two-three times per week for whatever reason, that’s fine.

In a similar vein, the type of conditioning that an individual performs is not really important from a health or non-specific performance standpoint. Therefore, priority should be given to an individual’s preference and access to various modalities such as running, cycling, rowing, swimming, calisthenics, etc.

For individuals who prefer to exercise at home and don’t have access to any conditioning equipment, we’d recommend doing light calisthenics such as jumping jacks, jogging in place, high knees, mountain climbers, etc. for the recommended HIIT. We’d also recommend doing two sessions per week of HIIT if you’re unable to find a suitable alternative for LISS. Finally, the daily step goals are to be completed in addition to the exercise.

We’ll again use RPE to gauge the intensity of our efforts, using the following scale: intensity, we use Rate of Perceived Exertion (RPE) to gauge effort as follows:

- RPE 6: More boring than difficult. Can carry on a conversation in full sentences.

- RPE 7: Easy effort. Can only talk in short sentences.

- RPE 8: Moderate effort, cannot speak comfortably.

- RPE 9: Hard effort. Near max effort.

- RPE 10: Maximal effort that is very difficult and not possible to sustain. All out sprint or pace.

Progression

Given the nature of this template, we don’t expect that most individuals will have the ability to add weight to their movements in small increments. We still expect that, on average, an individual should be getting stronger week-to-week when following appropriate programming, though individuals vary greatly in their response to a given training program (Ahtiainen 2016).

In general, we recommend trying to increase the reps or the weight that you’re using by about 1-5% each week while keeping the exercises, range of motion, tempo, rest periods, and target RPE the same from week to week unless otherwise specified.

Of course, life happens, and you may not always be able to add the desired amount in a given session within the parameters of the program, and that’s okay in the short-term. The idea is to assume you’ll be adding weight or reps until/unless proven otherwise based on how you’re actually performing during that training session.

On the other hand, if you end up not being able to reach your target RPE for a specified rep range using a particular exercise, we would recommend either increasing the rep range to a number that gets you to the target RPE or picking a different exercise variation that will. Both options are viable depending on your resources, e.g. equipment availability, time, etc.

What’s Next?

After completing this version of The At-Home Training Template, you’re in a position to choose what they want to do next with their programming depending on their goals. One option is to run the template again with different exercises. Alternatively, you may have access to more equipment or want more exercises to choose from, which are included in the full version of the At-Home Training Template. Finally, you might be interested in training at a gym or using more equipment like a barbell, squat rack, etc. In that case, we would advise individuals who were new to exercise prior to the At-Home Template to move on to our Beginner Template to get their feet wet with barbells. For more experienced lifters, we would recommend moving on to the Strength I, Powerbuilding I, Hypertrophy I, or General Strength and Conditioning I templates after completing The At-Home Template.