There are a variety of knee surgeries that may be recommended for an individual. These range from “minimally invasive” (also known as arthroscopic) surgeries, such as ACL reconstruction, to fully “open” procedures, such as total knee replacement. Regardless of the surgery performed, a well-designed rehabilitation program is essential for good outcomes and a return to normal activity.

This article will discuss what to expect when undergoing these procedures, as well as the general process for return to activity or sport. The discussion will mostly be framed through ACL reconstruction since this procedure has the most research evidence behind it. With that said, the general rehab process will be similar for most other procedures, including joint replacements for osteoarthritis which may be more familiar to many readers.

If you or someone you know are going through a surgical situation, reaching out to our Pain and Rehabilitation team for guidance will be useful to discuss specific procedural caveats that could affect individual recommendations and rehab timelines.

Preoperative Considerations

There are a wide range of qualifying criteria for an individual to undergo a surgical procedure. Additionally, there is significant variation in the initial recommendations a surgeon may provide for post-operative care. In some instances, this is due to the surgery being rarer, but for many procedures such as after ACL reconstruction or total knee replacement, there is good evidence in place for early movement and rehabilitation.

In other instances, a recommendation for surgery may conflict with the current best evidence for management of a particular condition. For example, the evidence shows that arthroscopic surgery for degenerative knee arthritis and meniscus tears is ineffective, yet the surgery is still performed frequently. Brignardello-Petersen 2017, Kim 2011 The American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons now has an official position statement recommending against arthroscopic debridement for osteoarthritis, but “expert opinion” is frequently used to justify the procedure anyway. If an individual has undergone these procedures, there are multiple steps that can be taken to return them to their prior level of function and beyond.

It is also important for the surgeon to understand the individual’s post-operative goals, as these may vary between a professional athlete undergoing ACL reconstruction or an older individual undergoing total knee replacement. In the context of ACL reconstruction, there is research on specific timelines for healing prior to full return to competitive sport. Claues 2011, Grindem 2011 An exclusive focus on the end goal undermines the training process that is necessary to get there, including the steps an individual needs to take in order to be prepared to return to their normal activities.

There is no discrete point after surgery where a joint is healed and everything is suddenly “okay.” The rehab process takes work on the part of the athlete and good planning on the part of the rehabilitation professional in order to:

- allow an athlete to train around their surgery,

- address deficits in strength and range of motion that occur as a result of surgery, and

- design a program to both condition an athlete as well as prepare them for the demands of not only their sport, but their position within their sport.

An open dialogue with your surgeon before surgery can help remove hurdles in this process.

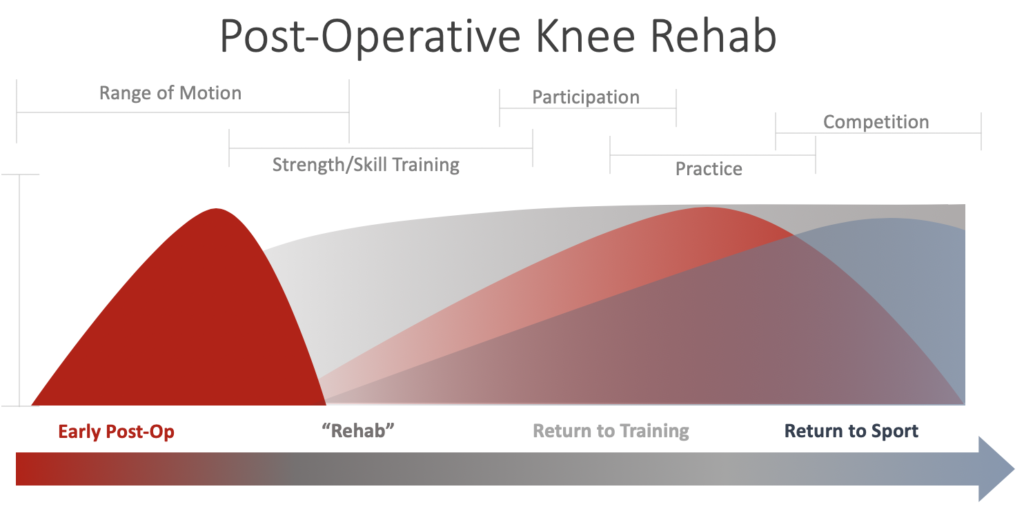

Figure 1 – The process for return to competition after injury.

Surgery is often viewed as a panacea to fix what is supposedly wrong with a joint. Unfortunately, this is not an accurate reflection of reality. While there are certainly instances where surgery is warranted, it is more likely that the work an athlete puts in before and after surgery has the greatest impact on outcomes. In the case of ACL reconstructions, even elite athletes only return to competitive sport 83% of the time. Lai 2018 That means 1 in 5 athletes never return to the professional level. In athletes younger than 25 years of age, the rate of reinjury after an ACL reconstruction is 23%.Wiggins 2016 In a study of over 7500 athletes, 81% of athletes returned to sport at any level, 65% returned to their pre-injury level, and only 55% returned to a competitive level of sport after surgery. Ardern 2014 There are multiple reasons why this occurs, including the aptitude of the surgeon, the effectiveness of post-operative rehabilitation, and even an athlete’s own social support and personal factors. These statistics are not shown to discourage athletes from undergoing a procedure, but rather to be very clear about the odds of success and the work that is necessary to return to full function or sport.

Managing expectations is an integral part of the process to help an athlete deal with stress (both related to healing and not being able to train/compete at their prior level), their motivation, and their identity as an athlete. Everheart 2015 If there are going to be range of motion or weight-bearing restrictions after surgery, knowing these ahead of time can help to develop a training plan around the injury. For example, an athlete can still undertake an upper body training program and even perform certain forms of conditioning if there are weight-bearing restrictions for the lower body.

The Early Post-Operative Phase

There are three main factors that will be discussed in regards to the rehabilitation process: psychology, biomechanics, and conditioning. While many rehabilitation plans are predicated almost entirely on biomechanical factors, this neglects a balanced plan that sees the athlete as a whole person. While the athlete’s knee may be the focus of the surgery, it is ultimately the person who is limited in what they want to achieve.

Primary factors such as swelling, range of motion, and weight-bearing status should be addressed prior to beginning other exercises. This is typically where rehab professionals tend to break out their “toolbox,” but the reality is that no laser, suction, needling, taping, or any other passive intervention has been shown to outperform the body’s own healing process. Emphasis should be on achieving the range of motion allowable within the constraints generated by the surgery, reestablishing a degree of normalcy in function, and developing a plan to begin training again.

It is worth expanding on what “healed” means in this context. It can be discussed in terms of a physiological state in which the tissue has returned to normal — but this is a misnomer. After surgery, there is no return to a prior “normal”, but rather establishing a “new normal” for the individual. This may be more obvious after a total knee replacement where there are new parts in place, but in other instances, such as after ACL reconstruction, the evidence suggests that physiological healing can take up to 9 months. Even then, joint kinematics are changed permanently after an ACL reconstruction. With this information, the narrative of “expediting healing” falls flat. There are also common tropes regarding decreasing inflammation, swelling, or bruising, which fail to recognize each of these as necessary steps in the healing process. Inflammation is often assigned a negative connotation after surgery, but the inflammatory process is a major pathway for physiological healing to occur.

Athletes are better served with a definition of healing that acknowledges there is more to being “healed” than what is going on within the operated joint. This expanded definition should include a more general readiness to return to their prior level of function. Rehabilitation is an athlete’s offseason. This time provides the opportunity to work on components of training that have likely been neglected and develop a broader base of athleticism.

To be clear, however: this does not mean using unsubstantiated assessments that give an athlete more problems than they initially presented with. For example, neither a “weak core” nor a “rotated hip” caused an athlete to get injured. If we are addressing the resilience of an athlete through the rehabilitative process, creating fictitious problems is not providing quality care.

Figure 2 – The phases of rehabilitation after surgery

Figure 2 illustrates the rehab process from early post-op to full return to sport. Note how no discrete times are assigned to the phases. This is because each is predicated on the specific type of surgery and healing of the individual athlete. For example, if an athlete undergoes a microfracture procedure and the surgeon advocates for non-weight bearing status for 6 weeks, this will shift the timeline. This does not mean that an athlete cannot work on skill development, conditioning, or strength in other areas, however. For example, a seated overhead press in a knee immobilizer is easy enough to perform.

Most outpatient rehabilitation involves 2-3 visits per week, but this neglects the conditioning component mentioned above. While an athlete may come into the clinic at that frequency, a program should also be provided to be performed outside of the clinic. If an athlete typically trains 5 days per week, there should be a plan in place to continue this frequency through the process, even if initially this involves exercises such as low-intensity conditioning on an upper extremity ergometer.

As part of the process, rehab clinicians may find management easier through athlete logs or regular check-ins. In today’s technological age, an athlete can just as easily upload a video from the gym as having performed the exercise in front of a clinician. This approach also removes the typical time constraints of appointments and can allow for more extended or abbreviated sessions as needed to meet an athlete’s current level.

“Rehab”

As range of motion begins to normalize, the focus shifts to addressing deficits that are a result of surgery, prior deconditioning, and symptoms such as pain. No two surgeries are the same, and an athlete who has had the misfortune of undergoing the same surgery twice will tell you they are often drastically different processes. A rehabilitation professional with experience in the athlete’s particular sport and with the particular surgery can be beneficial. One who can meet an athlete at their level and understand their goals is even more valuable, as they can design an effective program to meet those specific objectives.

The rehabilitation phase should involve progressive overload. If an athlete is 12 weeks after an arthroscopic surgery and is still only performing bodyweight exercises, we are likely missing the premise of progressive overload in their rehab. Exercise intensity should be determined through autoregulation, such as Rate of Perceived Exertion (RPE) or Reps in Reserve (RIR). True maximum effort (e.g., one-repetition max) should not be the goal until approaching return to sport phases, but determining intensity of exercise is integral for proper dosing. The initial phases may include exercises such as a terminal knee extension or long-arc quad exercise that can be hard (and near-maximal effort), but do not jeopardize the surgical site.

Both RPE and RIR allow for an athlete to determine how hard an exercise is accounting for both the technical constraints imposed by the clinician and the effort constraints imposed by the external loads. Within the constraints of rehabilitation, RPE and RIR may also be determined by whether an athlete can perform the repetitions within the technical proficiency the clinician provides. This will be determined on a case by case basis, at times with limits placed by the athlete and others placed by the clinician on being able to accomplish a certain component of a movement, such as depth in a squat. Constraints can also provide multiple variables as targets for improvement. In the example of a squat, there may be sets programmed through a tolerable weight, primarily focusing on the load on the bar. This often results in a movement through partial range, but that is okay. There may be other sets where the primary focus is on gaining more range of motion through a movement, or a more even weight distribution between legs. While the movement may be the same, the goal of the movement task may vary.

Initially, there may be large deviations away from task-specific constraints such as a pronounced weight shift onto the nonsurgical leg or not being able to squat to depth. Modifications can be made by either changing the exercise, or continuing to work the specific movement with a specific goal. The overall objective in this phase is to expand the limits of what an athlete can perform instead of attempting to push the limits on a narrow set of movements. While returning the ability to move in prior ways is important, there still are metrics that we seek to achieve regarding absolute strength in the surgical leg. In these instances, RPE would be used in a more traditional sense, directly related to maximal effort. If exercises with the in-set goal of increasing maximal strength are being rated at less than RPE 5/10, it is unlikely the athlete is receiving as much benefit from their work as they could with higher intensity work.

The primary focus should be more general physical preparedness and strength training as a means of getting an athlete ready for participation in their respective sport. The strength training component should identify any strength deficits that manifest after surgery and address them in an objective way. The method most often used is a manual muscle test (MMT), where a clinician imposes resistance with their hands to assess an athlete. The issue is that these tests are not nearly sensitive enough to determine any deficit beyond “strong enough.” If an athlete was squatting over 1.5 times bodyweight prior to surgery, it is unlikely any clinician will be able to accurately assess the strength of one quadriceps compared to the other using only their manual resistance.

In practical terms, a standard assessment of MMT for knee extension would involve an athlete sitting on the edge of the bed and kicking out into a clinician’s hand sitting in front of them. If an athlete was able to kick out 150 pounds of force on one leg, and 120 pounds on the other, they would have an 80% limb symmetry index (LSI) — but this depends on the clinician being able to discern that 30-pound difference. This is highly unlikely and would be even more problematic if an athlete were kicking out 200 lbs. with one leg and 140 lbs. with the other. Now, they would have a 70% LSI, but it is unlikely that many clinicians would be capable of picking this up given that 140 lbs. would likely exceed the force the clinician can generate against the athlete with their hands.

The current gold standard to assess strength is with a dynamometer. Here, there is much more accuracy and precision in measuring strength. There are also various other proxies that can be used if a dynamometer is not available, such as a unilateral leg press for a set at an assigned RPE, with one leg being compared to the other. Alternatively, the same comparison can be performed on a unilateral seated knee extension machine (although this is contingent upon the surgery, as there may be some time before knee extensions are permitted for maximal effort tests). Jewiss 2017

Rehabilitation should be an active process in which athletes are preparing for return to their respective sports. While there are numerous ways to strength train, at Barbell Medicine we tend to advocate for the utilization of barbells and other free weight implements to perform the fundamental movements of a squat and deadlift early on in the process. An athlete may start with an empty bar, but the repetitions early on will allow them to progress to increasing loads per their tolerance instead of waiting for a magical timeline or not including strength training in a program at all.

This is also the phase where single-leg work should be implemented to address strength deficits as well as begin sport-specific movements and proprioception. While addressing strength deficits is a high priority in the rehab phase, there are multiple movements specific to each sport that will need to be addressed. This is not advocating for silly movement patterns for the sake of some overly complex explanation. Exercises should be athlete specific and working towards a specific goal. Even with a movement such as cutting, a cornerback and wide receiver will perform the movements in a different manner.

In the past there has been concern over-stressing the surgical area too early. Evidence from Escamilla et al and various other studies demonstrate this concern is likely unwarranted. Escamilla 2012 The bigger problem is likely under-loading athletes, given that metrics such as squat depth have been shown to still be impaired 7 years after surgery. Sanford 2016 The lack of appropriate load through the rehab phase is likely why only 13.9% of athletes met ALL return to sport criteria in one study, while in the same cohort only 27.8% met strength metrics. Toole 2017 We can likely improve these metrics by designing training programs for athletes that address strength deficits and mimic a normal athletic training program.

This phase should reflect the basics of a well-designed training program; while the timeline may vary according to the individual surgery, the heuristic is the same. Athletes need to feel like athletes during rehabilitation. Metrics must be in place to prepare an athlete for return to participation in their sport. If this is not accomplished, we are doing a disservice to our athletes.

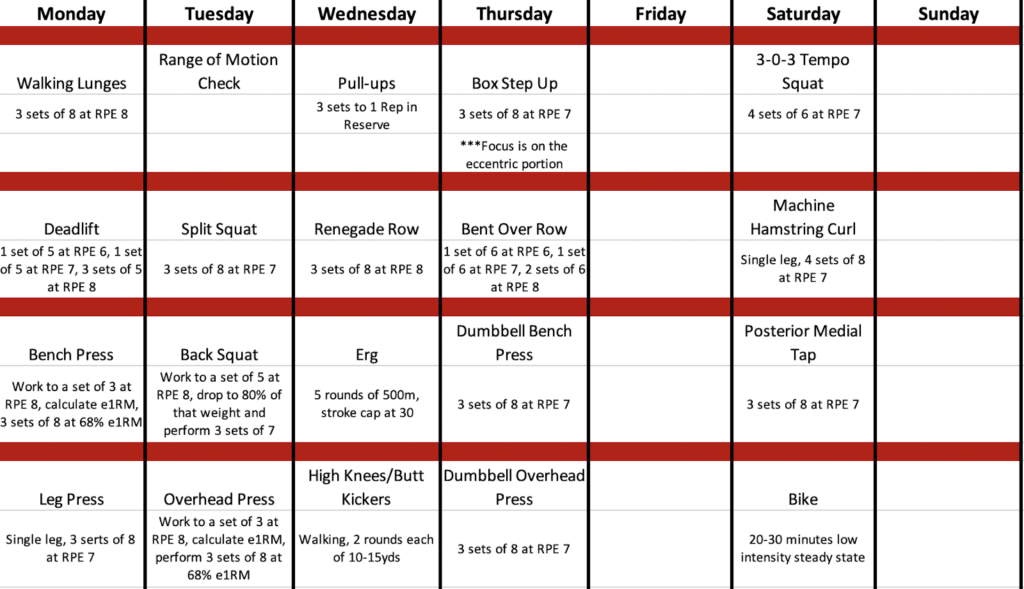

Figure 3 – Sample program of an athlete 11 weeks post ACL reconstruction, performing a 5-day split

During this time an athlete should also be gradually exposed to more volume, and to a certain degree intensity, to build towards future training demands. The goal is to return the athlete to their respective sport at a higher level than prior to injury, or at least prepared for pre-season training. This is likely unachievable with the typical 2-3 visits per week for possibly one-hour training sessions in traditional rehabilitation. There are often activities such as low-intensity steady state aerobic training that can be implemented in a program to develop a broader base of fitness without compromising the post-operative procedure.

Return to Participation

As an athlete begins to achieve strength metrics (i.e. a quadriceps limb symmetry index of 80%), it is time to begin the reintroduction of sport-specific work. This may include beginning to work on ball handling drills on the court or pitch or beginning to take batting practice. At this point, the process should be about introduction of movements and facilitating conditioning specific to their sport. During this phase, it is imperative that athletes continue their strength training and conditioning. There is no substitute for continuing with the fundamentals. While passing a strength test is good, the goal should be maximizing athletic potential.

In this phase, an athlete will begin change of direction, deceleration, and jump/landing work based on sport demands. The variation in movement for sport-specific task completion is likely to be high in early phases, but beginning exposure in a controlled environment facilitates the best outcomes. If these skills are not developed prior to return to sport, a large component of an athlete’s potential has been missed. It is essential to prepare athletes for their return to sport with a gradual ramp-up instead of forced inflection points dictated by time. No one expects to do well on a test for subject matter they have not been exposed to in months, and competition is effectively a test. Controlled skill development such as plyometric, agility, and landing drills have been shown to decrease the risk of re-injury and allows exposure with more constraints on the movement. Emery 2015

Return to Practice

Once an athlete gains exposure to sport specific drills in a controlled environment, they can be cleared for practice. Notice, there still needs to be a controlled environment step prior to full return to competition. While an athlete may feel “ready,” they need repetitions in a structured manner with their team prior to competition. When the goal of the day’s activities is getting better, there is a more natural governor in place than in competition where the primary objective is to win. This practice specific time also allows an athlete exposure to game-like activities with a reduced risk. Ideally, an athlete should be able to participate in at least 80% of practice activity prior to beginning discussion of return to competition.

It should also be emphasized here, yet again, that during this phase an athlete continues to participate in a well-designed strength and conditioning program to address any residual deficits. The fundamentals of athletic development do not disappear as one returns to sport. During practice, variables such as contact can also be limited so that an athlete can drill at a high level in a more controlled environment.

Return to Competition

While time is certainly a variable to consider after surgery, the decision to clear for return to competition should be based on additional factors. If an athlete has regained their strength in the surgical leg, participated in sports specific drills, worked on landing and change of direction drills then they are at a reduced risk of reinjury. Yet, sport does not exist in a vacuum. There will of course be other variables at play such as the level at which the athlete participates, the point in the season at which the injury and surgery occurred, and how their current team is faring. With that being said, most readers of this piece are not professional athletes. If the goal is to return to a recreational league, rushing return to sport may be frivolous if an athlete is underprepared. For surgical procedures such as an ACL reconstruction, there is a decrease risk of reinjury with a delayed return to sport. Grindem 2016

The other factor in return to competition that must be addressed is the athlete’s psychological readiness. It is important to ask how ready they feel to return to sport and if there are components of participation that are still raising concern.

“But I’m Not That Kind of Athlete!”

This piece is framed through returning an athlete to their respective sport with an emphasis more on team sports. As this is on the Barbell Medicine website, there is a good chance that readers are more concerned with returning to resistance training. If this is the case, the emphasis on change of direction and landing drills does not need to be as high. What does need to happen is finding ways for athletes to train early after their surgical procedures. A knee surgery is not the end of your lifting career and in most cases should be performed only as a means of facilitating lifting longer. There may be limitations on the types of movements an athlete can perform early after surgery, but under no circumstances does that mean they should not move or fear movement.

The initial phases of rehab may be relegated to traditional rehabilitation exercises for lower extremities such as isometric quadriceps contractions, straight leg raises, and range of motion exercises, but there must be progression. If you are used to running a four-day split in current training, the goal should be to meet that with a well-designed program. There will likely be a need for single-leg exercises, and possibly some movements that are not part of your normal programming. There can be more to a well-designed training program than just squats, deadlifts, and bench presses and their respective variants. Post-operative rehabilitation can be an opportunity to work on skills and exercises that you have never experienced and they can even have a place in your long-term routine.

If the goal is to return to a powerlifting or weightlifting competition, then the same progression mentioned above would hold. Participation would start with working through positional drills and other variations to reestablish technique. Practice would focus on the accumulation of prior volume so that you are adequately prepared to compete. If, however, the goal is to return to training, then the rehab phase can continue to work on any identified deficits and develop into a more rounded athlete. There should not be a great deal of difference between “rehab” and “training”, as both are meant to address any identified deficits that are limiting current goals. After surgery, there will likely be additional constraints, but the key is being able to work within those constraints to continue to train for a successful outcome.

Unfortunately, rehab often includes a passive approach, but getting better will always be an active process. Goals should be structured around the individual and predicated on objective measures. This means that we can track progress with the weight on the bar as well as how you are feeling. Different surgical procedures will have different timelines. For example, after a meniscectomy an athlete should be able to return to full training relatively quickly, whereas a procedure such as a microfracture will likely be a bit slower. If the process is slowed as a result of the procedure, that does not mean we cannot work on components such as pressing variations or use machines to train other body parts.

If you are struggling with returning to training after injury or surgery, you can reach out to us on the Pain and Rehab team for a consultation and development of a plan to get you where you need to be.

Edited by Austin Baraki, MD, Michael Ray, MS, DC, and Michael Amato, DPT