Spondylolysis or spondylolisthesis are two intimidating words that are often described as representing a “broken back”. These aren’t words anyone wants to hear when experiencing back pain. Doctors and physical therapists often provide complicated and ominous-sounding explanations, such as a “fracture of the pars interarticularis”. From the start there is so much complexity in this language that the person feels they are not only injured, but have failed a vocabulary exam. This article aims to demystify these diagnoses and offer reassurance and advice for returning to training.

Terminology

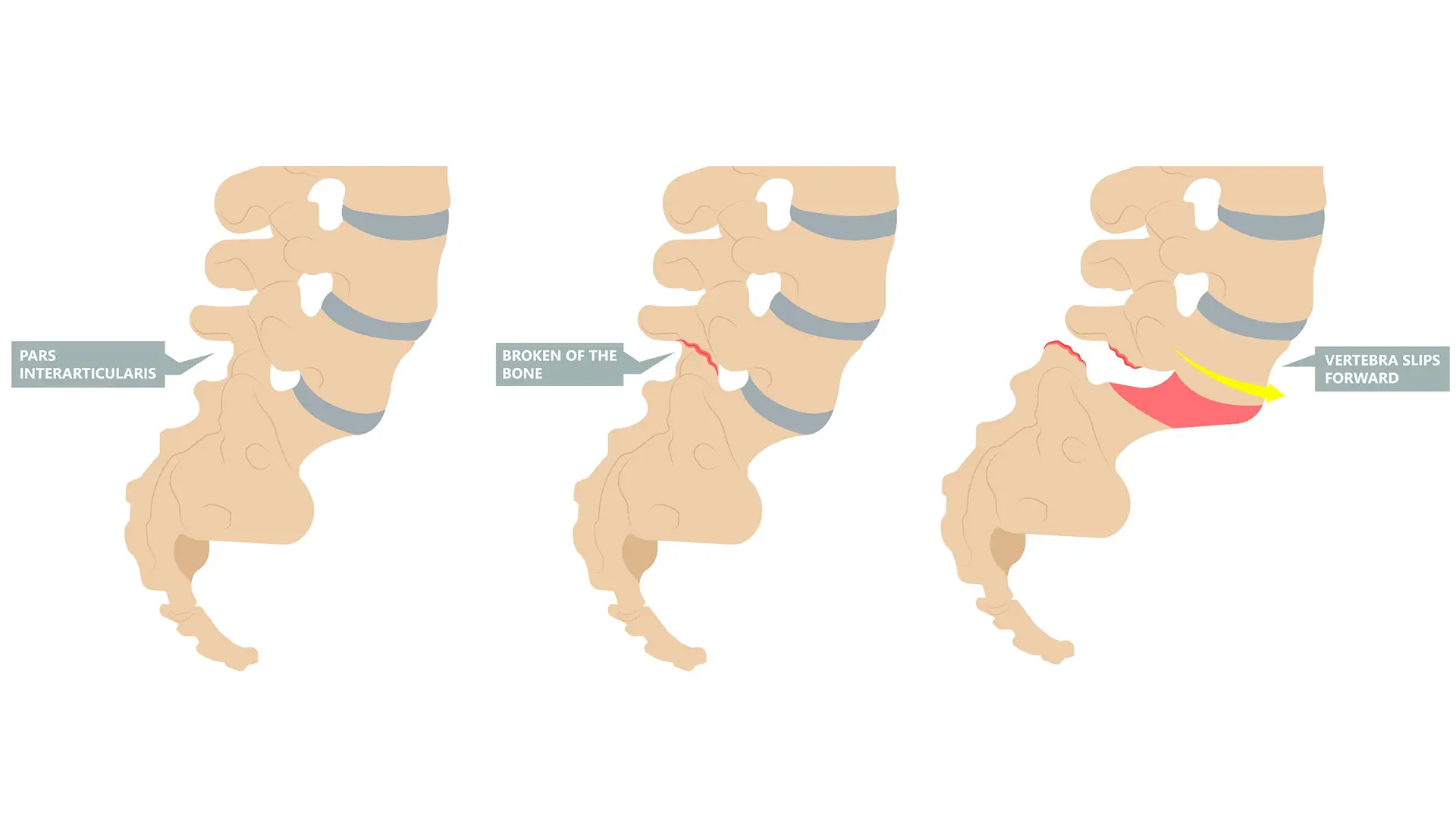

Let’s begin by getting the terminology out of the way. The spine (prefix “spondy-” is Greek for spine) is made up of a series of stacked bones known as vertebrae. Each individual vertebral bone has joints that link it to the neighboring bone above and below it. The pars interarticularis describes the bony bridge between these joints. “Spondylolysis” describes a fracture (suffix “-lysis”, meaning “break”) in the pars interarticularis. “Spondylolisthesis” (suffix “-listhesis”, meaning “slip”) describes a scenario where one vertebra moves forward relative to the one below it.

The rest of this article will group the two diagnoses together using the term “Spondy”, unless otherwise noted. While it might seem logical that a fracture or movement of the spinal joints would reliably cause back pain, we have 45 year follow-up studies that find no association between spondy and risk of back pain. This should sound familiar to our regular audience: pain is complex and is not always directly related to changes in the structure of our bones and tissues. This same study found that people with spondylolisthesis had slowed progression with aging, and none progressed to a point that would be considered problematic.

Unfortunately, common advice for patients with these diagnoses is to discourage movement due to fear of an increased “slipping,” even though this is not the case. There is one caveat worth noting when discussing back pain in general:

If you experience new problems with bowel or bladder function, such as incontinence or inability to urinate/defecate, or sensory changes like numbness in the groin region you should be evaluated by a medical professional immediately.

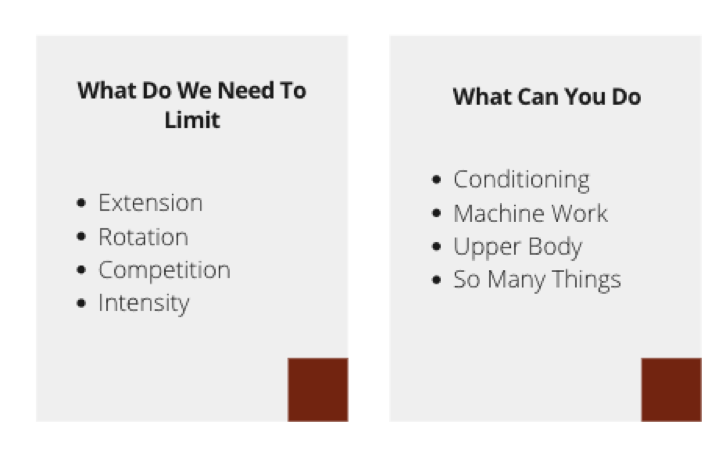

Most people end up receiving a spondy diagnosis after a sudden onset of centralized low back pain (pain that does not go into the legs). They are often quickly sent for X-ray or MRI testing. Once the diagnosis has been made, the person is left wondering whether it is safe to move, and if they’ll ever be able to get back to their prior activities. Clinicians often advise rest or avoiding certain activities, but there is no evidence that rest speeds up healing or helps people return to their prior level of function. No one has ever become a better athlete with absolute rest; there are always ways to stay active and maintain athleticism while pain symptoms calm down.

Base Rates

Before we can confidently say that something is a problem, we need to know how common it is found in the normal population who have no pain or other symptoms. This is known as the “base rate” of a condition. Unfortunately there isn’t much data to go on for spondy. As a result, treating this diagnosis falls more in the realm of expert opinion than rigorous scientific evidence.

The typical person diagnosed with spondy is an adolescent male who participates in an extension- or rotation-based sport like baseball or gymnastics. We can find spondylolysis in 3 to 7% of adolescents with no pain or other symptoms. This increases to 11.5% in the adult population with no pain or symptoms. This helps us properly frame the assessment of a person experiencing back pain in whom we find a spondy. In other words, for approximately 3-12% of these people, the finding would have been there all along without causing issues, meaning that it is unlikely to be directly causing the new back pain symptoms. We have good evidence that there is little correlation between experiencing back pain and having a spondy.

That is not to say the finding does not matter at all, but rather raises the question of whether it is a “contributor” more than a “cause”. An athlete coming from an off-season period to a sport that involves dramatic increases in low back extension and rotation is likely to need time to adapt, and may experience symptoms in the interim. An athlete in the same sport who is progressing to the next level of skill may experience the same phenomenon. That does not mean they need to be fully removed from sport, as this may take away too much of the stress needed for adaptation.

Most episodes of low back pain are complex and multifactorial, meaning that there are lots of contributors outside of the bones, muscles, and other tissues. Recent changes in training load or intensity can contribute to symptoms in other ways. Variables like adequate sleep, stress management, and general mental health also play a role in the experience of pain. More specific to the adolescent population, factors like early sports specialization and burnout need to be addressed as well.

There is no clear correlation between evidence of healing on imaging tests like X-rays and a successful outcome. One study found time and activity modification to be a stronger predictor of a successful return to sport, with no relationship between degree of healing and outcome. Other studies have similarly found little correlation between imaging findings and symptoms in the long-term. Our efforts are much better spent adjusting programming and stressors to the athlete to facilitate return to activities they enjoy, versus waiting a finite amount of time for an arbitrary change on an X-ray image. For some athletes, this may be removing a significant portion of their programming, for others it may be removing stress in one facet while adding it in another area to adapt. The following section will make suggestions for practical modifications.

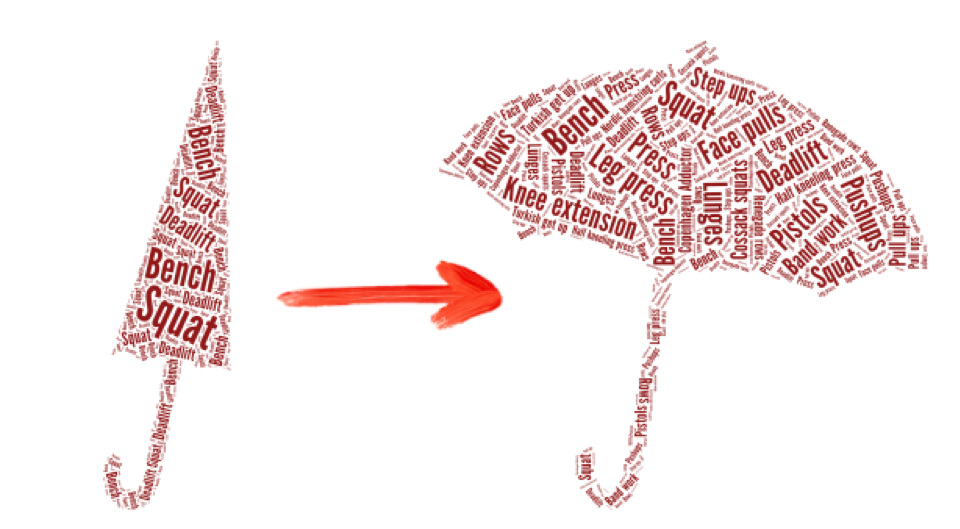

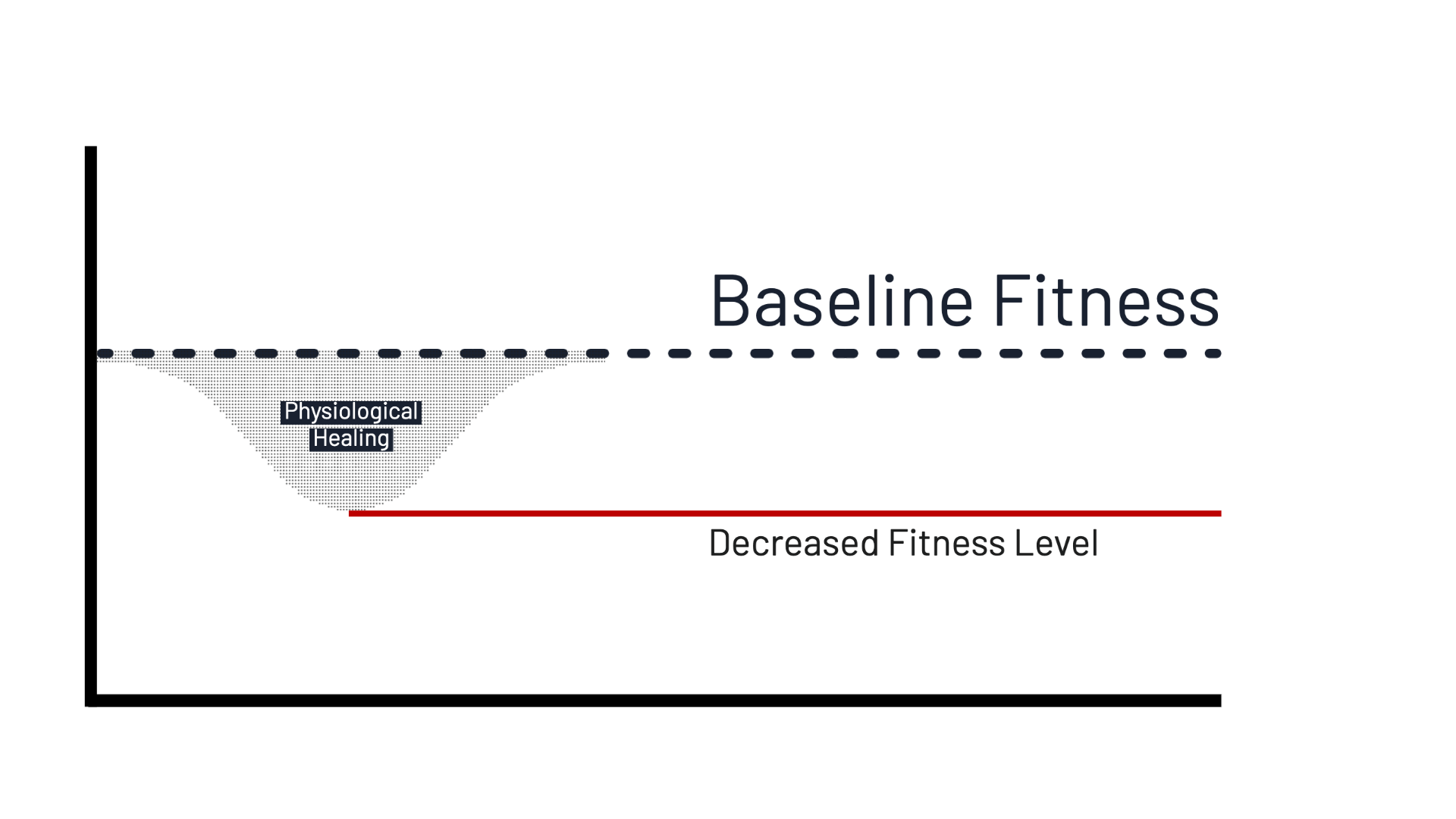

Short-term Program Adjustments

Most guidelines for managing spondy recommend “activity modification”, but this vague advice often ranges from absolute rest – which is not advised – to a series of random exercises thought to target certain muscle groups. The goal of any modifications should be to allow the athlete to train with minimal pain symptoms, while providing a sufficient stimulus to maintain their conditioning and athleticism in other ways. While an athlete may not be able to squat heavy, swing a bat, or participate in competition in the short term, there are countless other ways to stay active. Sometimes we need to open up the training program and tackle the issue from a different angle.

The “starting point” for each person will differ based on what they can tolerate. If pain started after a sudden injury and the person is experiencing a lot of pain, they may need to start with lower-level activities in order to keep moving and allow things to calm down. This can involve simple movements such as:

- Glute bridges

- Walking lunges

- Side-steps, with or without bands

These are things that would typically fall in a basic “physical therapy starter pack”. These exercises are not being recommended because of commonly cited reasons like “muscles being turned off,” “not firing properly”, or “needing to fire local muscles before global,” but rather because we sometimes just need to start easy as an entry point before progressing to do more. During this time, athletes should still train the upper body as normally as possible. They may need to make other modifications such as bench pressing with the feet up on the bench or limiting low back extension during overhead presses, but the goal should be to stay as athletic as possible while the pain calms down with time.

The other component of training should involve maintaining cardiovascular fitness. This can be achieved with low-intensity steady state aerobic activity on a bicycle, walking, or even pushing/pulling a sled. The main principle in the initial phase is to limit activities that push into end-range extension of the low back. As a result, rowing may be less preferable given the positions involved, although this can be incorporated in a later stage. The time component for the amount of cardio is specific to the demands of the athlete but the goal should be to at least build to physical activity guidelines of 150 minutes of moderate level activity per week.

As the person begins tolerating more activity, training should evolve as well. Someone may tolerate a belt squat machine as a means of loading the legs. Seated leg extensions and hamstring curls are also excellent substitutions for maintaining or building leg strength as well.

The typical steps of rehabilitation proceed as follows:

- Light and slow

- Heavy and slow

- Light and fast

- Heavy and fast

Heavy and light are always relative to the athlete. A lifter with a 1-rep max strength of 700 lbs and a novice with a max of 185 lbs will have different entry points to their rehabilitation. The former may be doing rehab exercises using the other athlete’s max without breaking a sweat. We will set a cap on the intensity of effort during the rehabilitation phase using ratings of perceived exertion (RPE). This will typically be capped at 7 in early stages, which allows for a wider margin for error. For example, a training set of RPE 7 accidentally becoming an RPE 8 is better than a set at 9 becoming a 10 if the goal is to build tolerance for movement. A general rule would be for “light” weight sets to be less than RPE 6, with RPE 7 or greater falling into the “heavy” category.

Symptoms should factor in here as well. When both symptoms and effort are rated on a 1-10 scale, the sum should rarely exceed 10 in short term adjustments. This may relegate an athlete with more acute, severe symptoms to very light loads. For example, an athlete rating their pain symptoms at 4/10 might limit their intensity up to the RPE 5-6 range. An athlete with symptoms rated at 8/10 might perform easy movements in a very low RPE range with a goal of simply moving over pushing for performance gains. As symptoms subside, an athlete can begin to push into higher-effort work. It also serves as an anchor that an athlete should be relatively symptom free prior to returning to max-effort training.

If an athlete participates in sports that involve rotation like baseball or gymnastics, scaled exercises that are more specific to these activities can begin. A drill may start with bodyweight and exploring the movement (e.g., a windmill) through tolerable range of motion, progressing to adding weight, and slowly going through full range of motion. As an athlete begins tolerating more load, they can incorporate drills that emphasize speed. This may involve swinging a lighter bat or basic stunts for gymnasts. For a barbell athlete it may involve back extensions or exercises on the glute-ham developer (GHD) machine with no weight, but a faster cadence.

The bottom line is that people are often instructed to wait too long, or to scale back activity too much, to the point where there is insufficient stress for healing and the athlete becomes unnecessarily deconditioned. The objective of any well-designed rehabilitation program should be to get an athlete feeling better, while also keeping them in shape as they progress towards return to sport or other desired activities. If we allow someone to return to sport due to evidence of “healing” on an X-ray, but they have not been conditioning, or even training since the time of injury, we are likely sending them back underprepared. Injury often provides an opportunity to build up components of training that have previously been lacking in the training program.

How to Train With Spondylolysis

As soon as someone can move through a full range of motion and tolerate activities of daily life without symptoms, they are okay to begin working with a barbell or other loaded implement again. The trajectory will depend on an athlete’s goals and training history. In some instances this may involve a bar weighing less than the standard 20 kg — but once again, the initial phase is just to “train” more than “gain”.

The equipment available to a person determines the training options available to them for rehabilitation. We will lay out advice for returning to the barbell lifts in an ideal scenario. There is no need to purchase specialty equipment, and people can change the intensity of exercises with the equipment they have in order to train productively. As mentioned above, we will set an arbitrary cap on the intensity of effort during the rehabilitation phase using an RPE of 7.

A beginner lifter can likely continue on their prior path following a program such as The Beginner Prescription or The Bridge, although they may need modifications in the early phase such as lowering target RPE by 1-2 points, and/or reducing the total number of work sets based on tolerance. A more experienced lifter who is used to running a low-rep scheme for their working sets (e.g., 1-3 reps) may need to transition through a block of training that would be considered more “hypertrophy”-oriented with higher rep targets and lower absolute loads.

The time frame for a return to fully “normal” squat, bench, and deadlift training can vary for each lift and from person to person. While the competition form of the lift may not be feasible, all exercises can be appropriately modified to where an athlete is performing some variation.

Squats

A safety squat bar (SSB) can be a useful tool as a means of axial loading using exercises such as a Hatfield squat. This allows the athlete to stay more upright and not force as much spinal extension in the early phase of training. It bears repeating that lumbar extension is perfectly fine in normal training conditions, but as movements are being reintroduced in a rehab context, constraints may be necessary to build tolerance. If SSB variations are not well-tolerated, an athlete may need to begin with a goblet squat using lighter weights while improving range of motion and control.

Machines such as a hack squat or leg press can also be used in the reintroduction phase. The initial goal is to have more constraints in place before allowing more freedom of movement as an athlete progresses. However, even as an athlete returns to a barbell back squat, these machines and variation of bars remain useful as supplemental exercises.

A typical programming scheme might involve squatting twice per week for 3-4 sets of 8-10 repetitions, working up to an RPE cap of 7. The movements can be done with a SSB or standard barbell, and a pin squat can be substituted if an athlete is having difficulty hitting their desired depth. The primary goal of the first session is to establish a tolerable range of motion, which will increase in subsequent sessions. In this way, the target RPE of 7 is anchored to “one pin lower than last session”. The goal of the next session may be increasing weight at the same pin height, and RPE is anchored to loading through that range. The time frame for increasing intensity will vary by athlete but we expect a typical athlete to tolerate full range of motion within 2-4 weeks. It is perfectly fine to wear a belt, knee sleeves, and shoes during this phase if desired, although these are not absolutely necessary either.

Bench Press

The bench press is typically limited most by the high-arch competition setup. Rehab can begin using a feet-up or flat-backed setup relatively early. Once again, pain symptoms are the primary indicator for progression. An athlete may be able to tolerate a feet-up bench press early on and can use this and a means of continuing to train. A machine chest press can serve as a substitute if bench pressing is not tolerable. Once ready to work into more spinal extension, the feet can return to the ground — or slightly elevated off the ground on plates — and begin working on leg drive and returning to the desired arch position for the competition-style bench press.

Another way of introducing lumbar extension is using a dumbbell incline bench press. With RPE still capped at 7, an athlete can begin to work into pressing with spinal extension with minimal risk of increasing symptoms. The same 3-4 sets of 8-10 reps, up to a cap of RPE 7 is a reasonable reintroduction strategy. As an athlete progresses, we use a hypertrophy-style, higher-rep training block before working up to heavier loads for low-rep sets at higher intensities.

Deadlift

Contrary to popular internet lore, it does not matter if a person deadlifts using conventional or sumo technique. To reintroduce a deadlift pattern, we can begin with any of a variety of exercises such as good mornings, Romanian deadlifts, or deadlifts from elevated blocks. An athlete may benefit from utilizing a sumo stance early on to allow for a more upright torso, although this may not be necessary. If an athlete finds one variation that is more tolerable than others, it can be used more for a training effect, whereas other variants for an exposure effect. This may look like the following:

Session 1

Any well-tolerated deadlift variation:

4 sets of 8 repetitions at RPE 6/7

Session 2

Any less-tolerated deadlift variation

4 sets of 8 repetitions at RPE 5 or 6

Session 3

Machine Hamstring curls

3 sets of 10 repetitions at RPE 9

Single-leg Romanian Deadlifts

3 sets of 8 repetitions at RPE 7

Conditioning & General Physical Preparedness (GPP)

The role of conditioning and general physical preparedness training cannot be overemphasized in this phase. The question is often whether an athlete needs to work “through”, or work “around” a problem. If training intensity is necessarily limited due to rehabilitation constraints, people will benefit from more exercise variation in other areas. This can involve continued use of machines or dumbbell exercises, and continuing to use movements involving spinal extension and rotation.

In this phase it is imperative that an athlete not “lose sight of the gym for the bar”. In other words, they should not become so focused on straight barbell-based movements that they forget to continue with a more broad-based fitness regimen.

We recommend using multiple exercises to emphasize lower back strength, and avoiding a myopic focus on conventional barbell deadlifts alone. These include glute-ham raises, back extensions, good morning variations, back extensions, and reverse hyperextensions. While we don’t have good scientific evidence for specific strengthening of the area, it stands to reason that the stronger an athlete’s back, the more stress it can tolerate in training and competition.

Returning to Sports Participation

As the diagnosis of spondy is seen more frequently in sports involving spinal rotation and extension such as baseball and gymnastics, we will also consider broad recommendations. Each sport will require individual starting points and emphasis, contingent upon the skill level of the athlete as well. A level 7 gymnast will start with a different set of exercises than a level 4. Following the same progression for rehabilitation, the “light and slow” phase may involve more movement-based skills that are not as challenging. For a baseball player, this could involve starting soft toss or swinging a wiffle ball bat.

There are times when an athlete may only need to shut down from competition but can still participate in drills and practice in a limited manner. Absolute rest, or even very limited rest with a “motor control”-oriented rehabilitation program often ends up creating an additional problem. While an underlying injury physiologically heal, the athlete is now out of shape and unprepared for return to sport. Most often, there is some exercise that can be tolerated as a means of staying in shape while progressing through rehab.

While the primary rehab focus is on addressing lower back symptoms, the overall goal is a full, safe return to sport. If an athlete has spent three months performing 2 hours of “rehabilitation” per week with the goal of returning to 10 hours of sports participation, no amount of exercise in that time frame can adequately compensate for the volume of training lost. If an athlete is able to train, even with low intensity cardio work, they are better positioned to return to sport as overall volume and intensity increase.

As an athlete begins to tolerate full range of motion without symptoms through slower movements, speed needs to be gradually reintroduced. A baseball player may progress from soft toss to limited pitching off the ground or mound. A gymnast may progress from single stunts to chaining multiple stunts together. This does not mean that they forgo basic strength training; as part of general physical activity guidelines, adolescents and adults should be all participating in strength training at least twice per week. This does not mean every athlete needs to be using a barbell, but external load is necessary to facilitate adaptation for both health and performance. What constitutes “sufficient” load is also unique to the person, and we favor using autoregulation (RPE) as a means of determining that load on a daily basis. It is also perfectly safe and encouraged for youth to participate in resistance training. For parents interested in reading more on this topic, we have a whole series that can be found here.

Returning to Competition/Full Intensity

After an athlete has returned to training/practice, the next question is ultimately when it is appropriate to compete or perform max effort lifts. The last phase of the rehabilitation progression is “heavy and fast”. It is common for a lifter to progress to 75-80% of prior lifts and experience a stall. Often this is as much due to confidence with the weight as it is ability, and a small jump in weight can create a dramatic increase in the perception of effort. If this occurs, it can be advantageous to use “drop sets” in programming. For example, if a set of 4 repetitions at 315 pounds is rated RPE 7, but 4 reps at 325 pounds is rated RPE 10, it can help to program small drops in weight and emphasize speed through the repetitions. If an athlete can perform a lift for significantly more reps at the same effort with a 3-5% drop, this can be a means of building confidence back for maximum effort.

For a ball sport athlete, exercises need to be integrated into contact drills (where applicable) prior to return to sport. It is one thing to perform a movement in a sterile setting without an opponent, and another entirely to have an opponent in the way, giving their best effort to keep an athlete from moving how they want. It also may involve playing different positions to limit maximum effort in the initial phase. For example, a baseball player may need to start out on first base prior to transitioning back to the outfield to limit long throws. The process will be different for each sport and it is necessary for coaches and rehabilitation professionals to understand the demands and be able to apply the time and space necessary to prepare an athlete for return to sport.

To summarize the overarching concept: no parent would think it a good idea to have their child take three months off from a subject in school then return to a test. We should not take that approach with sport either, as competition is ultimately a test of their athletic development.

Wrap-Up

While it can sound scary to receive a diagnosis like spondylolisthesis or spondylolysis, outcomes are good with conservative care, including modifying activity and limiting competition. Athletes do not need a specific set of exercises; they may benefit more from broadening the scope of their training during rehabilitation to remain as conditioned as possible for their sport as symptoms settle down. Without a specific mechanism of injury, it is difficult to correlate symptoms with findings on imaging tests like X-rays and MRIs. In the adult population, “acute” spondys are rare, and when they do appear on imaging, could also be from a prior activity.

If you are struggling with your rehabilitation process, you can reach out to the Pain and Rehab team for a consultation and assistance with returning to the activities you love.

Special thanks to Dr. Austin Baraki and Dr. Salinda Chan for their help with this article.