Have you ever been told you have “arthritis” in one of your joints? Do you know anyone who said they have “bad knees” or who underwent surgery to replace a joint? Given how common osteoarthritis (OA) is across the world, the odds are that the answer to at least one of these questions is “yes”.

If you have experience with this condition, you may be wondering what can be done about it. Unfortunately, myths and misinformation about osteoarthritis are pervasive and persistent. These ideas often lead to poor management of this condition, resulting in decreases in quality of life compared to what can be achieved with more effective approaches. In this article we hope to provide education about the topic, dispel common myths about osteoarthritis, and provide some of these more effective strategies to gain control over its impact on your life.

What is Osteoarthritis?

Osteoarthritis describes a condition that may involve joint pain, stiffness, and limitations in range of motion. It affects the knees in over 80% of all cases, but can also affect the hips, hands, and shoulders of middle-aged and older adults [1,2].

A commonly held belief is that osteoarthritis results from “wear and tear” of joint cartilage. It is then assumed that this leads to a joint being “bone on bone”, and that this joint damage is the source of pain. This can be a compelling explanation when it seems to fit with the experience of joint stiffness, grinding, and “snaps, crackles, and pops” known as crepitus. This is further supported when doctors show patients their X-rays and point out areas of joint “degeneration”. This conveys the idea that the severity of arthritis as it appears on an X-ray is closely related to the severity of pain and disability.

Thankfully, the situation is more complex than what these explanations seem to convey. While it is true that osteoarthritis typically involves thinning of joint cartilage, the cause is not the same type of ‘wear and tear’ that you might associate with a mechanical car part wearing out. In fact, it is extremely common for people to develop the appearance of osteoarthritis on X-rays with age, whether or not they experience joint pain at all. We avoid applying unnecessarily ominous labels like “degeneration” that are commonly used in the medical world, and instead view this as a normal age-related change, analogous to the development of grey hair or skin wrinkles.

The poor relationship between X-ray findings and patient symptoms reflects the reality that pain is not an accurate reflection of tissue damage; rather, pain is a complex experience that can be influenced by a wide variety of factors both inside and outside of a joint. There are patients with no abnormalities on their X-rays who experience a lot of pain, there are patients with significant abnormalities on their X-rays with no pain, and everything in between. This is not to say that these age-related changes can’t play a role in the development of joint pain, just that they don’t give us the whole picture on their own. In fact, there is currently a movement to transition away from an excessively “joint-focused” view of osteoarthritis, and instead to view osteoarthritis as a ‘whole person condition’ that is influenced by various factors outside the joint as well.

For example, the development of osteoarthritis is associated with a variety of biological factors such as bony changes, genetics, traumatic injury, and the presence of other medical conditions including carrying excess body fat. In addition, pain symptoms are also associated with several psychological, social, and environmental factors including poor sleep, negative beliefs, fear, depression, anxiety, stress, and a decreased sense of control and ability (known as “self-efficacy”). These factors interact to cause decreases in physical activity and engagement with life — often due to fear of causing more damage — which then leads to worsening symptoms and further disability. [3,4,5,6] This is illustrated in the diagram below, which summarizes the consequences of negative, harmful beliefs when it comes to arthritis:

Bunzli et al. Misconceptions and the Acceptance of Evidence-based Nonsurgical Interventions for Knee Osteoarthritis. A Qualitative Study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2019 Sep;477(9):1975-1983. Doi: 10.1097/CORR.0000000000000784.

Adopting the whole-person perspective instead of focusing exclusively on joint damage has important implications for management. Shifting the focus from the joint to the whole person gives us more potential opportunities for intervention to improve function and quality of life, rather than instilling the erroneous idea that fixing damage by joint replacement is the only plausible option [7].

Common Misconceptions

A 2019 study conducted a survey on patients who were scheduled for knee replacement surgery. The authors found that all of the participants believed that their knee was “bone on bone” as a result of “wear and tear”. This belief led them to avoid painful activities out of fear of causing more damage to the joint [8]. In this section, we’re going to examine these beliefs identified in this study in order to address common misconceptions about knee osteoarthritis.

When asked about their knee arthritis, patients said:

“It’s bone on bone, the cartilage is gone in it,”

“One day I was walking good, the next day bang … the bone was catching on bone. You can feel it actually grinding,”

“Sometimes if I turn, you’ll hear this big crack. And then it’s as if it comes out of its socket, I don’t know if it pops out but there’s a loud cracking sound.”

“They’ve shown me the pictures of the inside of my knees, it is literally just two round circles—balls—with nothing on them.”

Main theme: Knee osteoarthritis is “bone on bone”

The facts: There is certainly some truth to the idea of cartilage loss as it relates to osteoarthritis. But while these structural changes have the potential to contribute to symptoms of arthritis, there are many more factors that influence whether a joint becomes sensitive and painful.

You may be surprised to learn that up to 43% of people over the age of 40 will show knee osteoarthritis changes on MRI images without any pain or other symptoms. We also have evidence showing that people can experience significant improvement in their pain and function despite the joint structure not changing. Finally, about 20% of patients still experience knee pain after total knee replacement. All of this serves to illustrate how pain is more than just tissue-level changes or “damage”. To reiterate: this is good news, since it means we have lots of variables to work on to promote joint health and function rather than pinning all of our hopes on surgery. [9]

With respect to the ‘grinding’ or ‘cracking’ sounds that folks often experience, known as “crepitus”, we have an article addressing this topic here. Patients are typically most concerned about the meaning of these noises, and assume that the noise reflects ongoing damage to the joint from it being “bone on bone”. However, much like the X-ray findings described above, crepitus is also extremely common in individuals who have normal joint function and no pain. Creptius does not reflect active damage to a joint, even though it can sound scary — in fact, our joints need motion and exercise to be healthy.

When asked about what caused their knee osteoarthritis, patients said:

“I always did a lot of gardening and dancing in my youth, maybe some of that contributed as well,”

“Look, it’s wear and tear … I expected this, I’m a hard worker,”

“Putting on weight doesn’t help your knees. Because you’ve got to carry it around,”

Main theme: OA is due to excessive loading through the knee.

The Facts: If we view the body as a machine composed of mechanical parts like a car, the idea of “wear and tear” seems to make sense. It leads people to conclude that the stress of repeated bending, loading, or use of the joints leads to degradation over time until replacement is required. However, the fundamental assumption here — that our body parts are like the components of a machine — is incomplete.

It is essential to recognize the differences between living things that readily adapt to stimuli, and non-living things that lack this ability. If cars had the ability to adapt, their tires, wheels, axles, and engines would become bigger and stronger with time. This does not happen, of course, which is why machines make poor analogies for understanding humans. So, instead of worrying about “wear and tear”, it is important to recognize that we can actually repair and adapt to stimuli like bending, loading, and moving our joints.

This is not to say that loading is irrelevant to joint pain, however. For example, we know that traumatic injuries to the knee joint (for example, ACL tears) increase the risk for developing osteoarthritis later in life [10]. However, more routine, non-traumatic loading doesn’t seem to significantly increase the risk of osteoarthritis-related pain and doesn’t harm articular cartilage [11a]. In fact, one study used MRI to compare the knees of competitive weightlifters to healthy controls, and found that weightlifters actually had significantly thicker knee cartilage, and that the earlier they began training, the thicker their cartilage became. [11b] These findings may seem surprising, but would fit perfectly in line with an understanding of humans as adaptable organisms rather than machines.

Neither routine exercise with weights nor aerobic activity such as running causes arthritis. In fact, progressive strength training can help improve muscle strength, pain intensity, physical function, and self-efficacy, even among patients with advanced arthritis [12-16]. Similarly, self-selected running is associated with improved knee pain and does not cause damage to the joint either [17].

Staying physically active with knee osteoarthritis is important for staying independent and healthy, especially given the risk of chronic diseases associated with being sedentary [18]. The take home message here is that we should not worry about “wear and tear”, but rather recognize that inactivity is likely more harmful than engaging in activities to which we can adapt. We should therefore engage with life and physical activity, loading our joints to increase capacity instead of avoiding it out of misplaced fears of damage.

When asked about how their symptoms would change over time, patients said:

“If I keep going the way I am going, it’s just going to get worse. It will just rub, rub away,”

“When he looked at the x-rays, he showed me the left-hand side is just bone on bone, there’s nothing there. He said it’s not going to get any better, as a matter of fact it’s going to get worse,”

“The knee has already past its used-by date, so it has to have something to replace it,”

Main theme: OA is an inevitable downward trajectory.

The Facts: A common misconception about knee osteoarthritis is that progressive joint degradation is inevitable, and that this ultimately requires a knee replacement. However, the progression of knee osteoarthritis is highly variable between individuals and many people do not show worsening symptoms or advancing joint changes even over the course of several years [19,20,21a].

It is known that a lack of regular physical activity is among the most prevalent risk factors for declines in function in patients with osteoarthritis [21b]. This gives us a good target for interventions to mitigate progression or generate improvement in pain and function, even in those with advanced osteoarthritis. For example, among patients with moderate to advanced osteoarthritis who were deemed eligible for knee replacement surgery, a simple exercise program resulted in 75% of patients declining the operation at 12 months and 68% declining at 2 years [22,23]. But when people with advanced osteoarthritis perform regular exercise and experience significant improvement in pain and function, their thoughts are often preoccupied with knee pain, knee damage, and the belief that they will inevitably need a knee replacement [24]. These beliefs can present significant challenges in the course of care and benefit from education and reassurance from a caring clinician.

This is not to say that surgical joint replacement is never beneficial or necessary. In fact, it is a generally successful surgery when performed on appropriately selected patients. The overarching theme of our approach is that patients should receive high-quality, evidence-based care up front prior to consideration of whether surgery is needed. When such care is offered first, a large proportion of patients experience significant improvement and can comfortably defer or avoid surgery altogether. So when patients with advanced osteoarthritis have not improved with appropriate non-surgical care (which includes adequately-dosed exercise), a collaborative process can guide decision making about whether they are a good candidate for surgery [25]. Ultimately, if surgery is the right option, engaging in an exercise program beforehand can help patients get back to their lives sooner, with less pain and disability [26].

Management Strategies

Based on a variety of official clinical practice guidelines, the first-line recommendation for the management of osteoarthritis include self-management programs, exercise, and engaging in physical activity consistent with national guidelines (or progressing towards meeting them over time) [27,28,29].

Unfortunately, real-world clinical practice varies considerably between healthcare providers with respect to providing evidence-based education and adhering to these guidelines [30,31,32,33,34]. Instead, the usual pattern involves inaccurate education based on outdated ideas that focus excessively on tissue structure and damage, often resulting in more fear of movement and activity. Emphasis also tends to to be placed on using medications and injections to manage osteoarthritis, including (but not limited to):

- Oral acetaminophen (also known as paracetamol, or Tylenol)

- Oral non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs like naproxen or ibuprofen)

- Oral opioid medications (e.g., hydrocodone, oxycodone, tramadol, etc.)

- Topical therapies (e.g., diclofenac gel, capsaicin cream)

- Injection therapies (e.g., corticosteroid injections including triamcinolone, anesthetic injections including lidocaine, platelet-rich plasma injections, hyaluronic acid injections)

- Supplements (e.g., glucosamine, chondroitin, etc.)

There is a substantial amount of evidence to suggest that many of these commonly used treatments offer transient, minor, or no benefits over placebos [35]. While there may be a role for these interventions for offering short-term pain relief, they should not be emphasized over the established first-line approaches including self-management programs, physical activity, and graded exercise. Similarly, many rehab clinics offer a number of interventions that are done “to” the patient, such as massage, needling, ultrasound, TENS, and other therapies, rather than progressive exercise and self-management programs. These are also ineffective and do not replace the need for active, adequately-dosed exercise interventions.

Within the “whole-person” perspective of osteoarthritis, it is also important to address other aspects of health that can contribute to symptoms and joint sensitivity. We have a dedicated article on general health that can be found here. These include things like depression, anxiety, stress, and worry, which may benefit from working with a mental health professional. Other medical conditions, including carrying excess bodyfat, can contribute to symptoms from osteoarthritis, so working with a healthcare team including physicians, dieticians, and health coaches may help achieve sustained fat loss. [36]. Finally, sleep is critically important for health and can influence individuals’ experience of pain, facilitate recovery from exercise, and has a number of other important functions. Interventions to improve sleep quality, as well as evaluating and treating other sleep disorders such as obstructive sleep apnea or insomnia are an important component of treatment for pain-related conditions as well.

Physical activity and Exercise

When it comes to physical activity and exercise, many patients are unsure of what exercises they should or shouldn’t be doing. For example, many patients are concerned with squatting-type motions that bend and load the knees and hips. It turns out that the exact type of exercise doesn’t seem to matter as much as simply engaging in a physical activity on a regular basis. There are also no specific movements that are uniquely harmful, that should be avoided, or that must be done in a very particular way. There are no right or wrong ways to move, and we’d prefer patients gain the strength, ability, and confidence to move in a wide variety of ways.

For example, we often like to get patients who are unaccustomed to exercise started with “sit-to-stands” from a chair, as a way to improve hip and knee strength, as these are key to physical independence. This starting point can be progressed to “sit-to-stands” while standing on an elevated surface (as a way to increase the range of motion of the movement) and/or holding a weighted object in front, and eventually to squats without a chair.

Rather than being concerned about “moving wrong” and “wear and tear” on our joints, we need to recognize that humans can adapt to a huge variety of stimuli. The stimulus of exercise actually results in our joints adapting and getting stronger, but this requires an appropriate dose of stimulus — not too much, and not too little. The key with physical activity in the context of pain symptoms is to “start low and go slow”, using movements that involve the affected area in a tolerable way. If there are specific movements or activities that an individual has been avoiding, we often aim to challenge those fears through our exercise program over time as well.

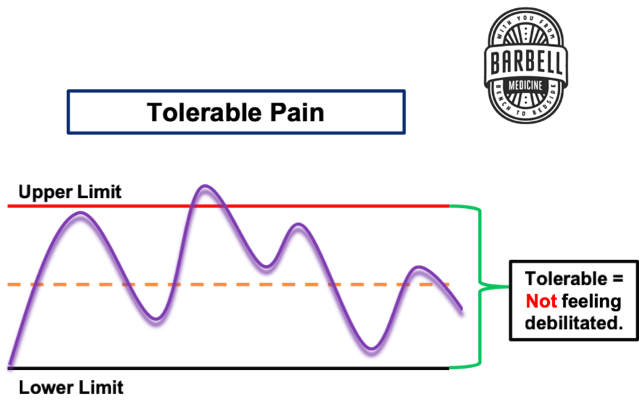

It is common for people to experience symptom fluctuations and pain flare-ups for a variety of reasons. It is expected to experience some degree of symptoms with activity, particularly at first. As we have hopefully conveyed so far, it is important to remember that pain does not equal tissue damage or harm. So if symptoms remain tolerable and don’t spike to debilitating levels during or after your exercise session, then you should be just fine to continue on (see Fig. 1 below). If symptoms do increase drastically, on the other hand, modifications to the dosage or type of activity are probably required; this may involve reducing the load, intensity, or volume of exercise to a more tolerable level and progressing from there.

Other factors may also play a role in symptom flare-ups over time, including life stresses, poor sleep, anxiety, unaccustomed activities or loading, and many others. These may result in a need to temporarily adjust the dosage of exercise while working on these other factors. This serves to underscore the importance of the “whole-person” perspective on osteoarthritis, rather than exclusively focusing on the joint alone.

Using this approach of exercising within a ‘tolerable’ level of symptoms can help to build more confidence in your abilities and allow you to gain control over your situation (known as self-efficacy). This tends to result in better long-term outcomes than being entirely dependent on the healthcare system to “fix” your joint for you — which isn’t really possible anyway [37,38]. If you are unsure of where to begin, there are numerous resources available on the internet such as this one for building your own exercise program. For those interested in more specific guidance, we offer exercise-based rehab templates for the knee or back, as well as individualized Pain & Rehab consultations and coaching for those dealing with pain-based issues.

Thank you to Dr. Michael Ray and Dr. Michael Amato for their assistance in editing this piece.

References

[1] GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018. Nov 10;392(10159):1789-1858. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32279-7.

[2] Wallace IJ, Worthington S, Felson DT, Jurmain RD, Wren KT, Maijanen H, Woods RJ, Lieberman DE. Knee osteoarthritis has doubled in prevalence since the mid-20th century. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114(35):9332–6.

[3] Rejeski W.J., Martin K., Ettinger W.H., Morgan T. Treating disability in knee osteoarthritis with exercise therapy: A central role for self-efficacy and pain. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;11:94–101. doi: 10.1002/art.1790110205.

[4] Martel-Pelletier J., Barr A.J., Cicuttini F.M., Conaghan P.G., Cooper C., Goldring M.B., Goldring S.R., Jones G., Teichtahl A.J., Pelletier J.-P. Osteoarthritis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 2016;2:16072. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2016.72.

[5] X. Wang, D. Hunter, J. Xu, C. Ding, Metabolic triggered inflammation in osteoarthritis, Osteoarthritis and Cartilage, Volume 23, Issue 1, 2015, Pages 22-30.

[6] Spector T.D., MacGregor A.J. Risk factors for osteoarthritis: Genetics. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2004;12(Suppl. A):S39–S44. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2003.09.005.

[7] Caneiro J, O’Sullivan PB, Roos EM, et alThree steps to changing the narrative about knee osteoarthritis care: a call to action. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2020;54:256-258.

[8] Bunzli et al. Misconceptions and the Acceptance of Evidence-based Nonsurgical Interventions for Knee Osteoarthritis. A Qualitative Study. Clin Orthop Relat Res.2019 Sep;477(9):1975-1983. doi: 10.1097/CORR.0000000000000784.

[9] Culvenor AG, Øiestad BE, Hart HF, et al. Prevalence of knee osteoarthritis features on magnetic resonance imaging in asymptomatic uninjured adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2019;53:1268-1278.

[10] Paschos NK. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction and knee osteoarthritis. World J Orthop. 2017;8(3):212-217. Published 2017 Mar 18. doi:10.5312/wjo.v8.i3.212

[11a] Bricca A, Juhl CB, Steultjens M, et alImpact of exercise on articular cartilage in people at risk of, or with established, knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review of randomised controlled trialsBritish Journal of Sports Medicine 2019;53:940-947.

[11b] Grelak et al. Thickening of the knee joint cartilage in elite weightlifters as a potential adaptation mechanism. Clin Anat. 2014 Sep;27(6):920-8. doi: 10.1002/ca.22393.

[12] Rejeski WJ, Ettinger WH Jr, Martin K, Morgan T. Treating disability in knee osteoarthritis with exercise therapy: a central role for self-efficacy and pain. Arthritis Care Res. 1998;11(2):94-101. doi:10.1002/art.1790110205

[13] Kristensen J, Franklyn-Miller A. Resistance training in musculoskeletal rehabilitation: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2012;46(10):719-726. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2010.079376

[14] Vincent KR, Vincent HK. Resistance exercise for knee osteoarthritis. PM R. 2012;4(5 Suppl):S45-S52. doi:10.1016/j.pmrj.2012.01.019

[15] Jan MH, Lin JJ, Liau JJ, Lin YF, Lin DH. Investigation of clinical effects of high- and low-resistance training for patients with knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Phys Ther. 2008;88(4):427-436. doi:10.2522/ptj.20060300

[16] Tanaka R, Ozawa J, Kito N, Moriyama H. Efficacy of strengthening or aerobic exercise on pain relief in people with knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin Rehabil. 2013;27(12):1059-1071. doi:10.1177/0269215513488898

[17] Lo GH, Musa SM, Driban JB, et al. Running does not increase symptoms or structural progression in people with knee osteoarthritis: data from the osteoarthritis initiative. Clin Rheumatol. 2018;37(9):2497-2504. doi:10.1007/s10067-018-4121-3

[18] Booth, F.W., Roberts, C.K. and Laye, M.J. (2012). Lack of Exercise Is a Major Cause of Chronic Diseases. In Comprehensive Physiology, R. Terjung (Ed.). doi:10.1002/cphy.c110025

[19] Kittelson AJ, George SZ, Maluf KS, Stevens-Lapsley JE. Future directions in painful knee osteoarthritis: harnessing complexity in a heterogeneous population. Phys Ther. 2014;94(3):422-432. doi:10.2522/ptj.20130256

[20] Spector TD, Dacre JE, Harris PA, Huskisson EC. Radiological progression of osteoarthritis: an 11-year follow-up study of the knee. Ann Rheum Dis. 1992;51:1107–1110

[21a] Chapple CM, Nicholson H, Baxter GD, Abbott JH. Patient characteristics that predict progression of knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review of prognostic studies. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2011;63:1115–1125

[21b] Dunlop et al. Risk factors for functional decline in older adults with arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2005 Apr;52(4):1274-82. doi: 10.1002/art.20968.

[22] Skou ST, Roos EM, Laursen MB, Rathleff MS, Arendt-Nielsen L, Simonsen O, et al. A Randomized, Controlled Trial of Total Knee Replacement. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(17):1597-606. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa1505467

[23] Skou, S.T. et al. Total knee replacement and non-surgical treatment of knee osteoarthritis: 2-year outcome from two parallel randomized controlled trials Osteoarthritis and Cartilage, Volume 26, Issue 9, 1170 – 1180: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2018.04.014

[24] Jason A. Wallis, Kate E. Webster, Pazit Levinger, Parminder J. Singh, Chris Fong & Nicholas F. Taylor (2019) Perceptions about participation in a 12-week walking program for people with severe knee osteoarthritis: a qualitative analysis, Disability and Rehabilitation, 41:7, 779-785, DOI: 10.1080/09638288.2017.1408710

[25] Hunter DJ. Osteoarthritis: time for us all to shift the needle. Rheumatology 2018;57(suppl_4):iv1–2.

[26] Topp R, Swank AM, Quesada PM, Nyland J, Malkani A. The effect of prehabilitation exercise on strength and functioning after total knee arthroplasty. PM R. 2009;1(8):729-735. doi:10.1016/j.pmrj.2009.06.003

[27] ACR. 2019 American College of Rheumatology/Arthritis Foundation Guideline for the Management of Osteoarthritis of the Hand, Hip, and Knee.

[28] AAOS. Clinical Practice Guideline: Treatment of Osteoarthritis of the Knee, 2nd Edition.

[29] AAFP. Treatment of Knee Osteoarthritis. Am Fam Physician. 2014 Jun 1;89(11):918-920.

[30] Cottrell et al. “The attitudes, beliefs and behaviours of GPs regarding exercise for chronic knee pain: a systematic review.” BMC family practice vol. 11 4. 18 Jan. 2010, doi:10.1186/1471-2296-11-4

[31] DeHaan et al. Knee osteoarthritis clinical practice guidelines — how are we doing? J Rheumatol. 2007 Oct;34(10):2099-105. Epub 2007 Aug 15.

[32] Mazzuca et al. Comparison of general internists, family physicians, and rheumatologists managing patients with symptoms of osteoarthritis of the knee. Arthritis Care Res. 1997 Oct;10(5):289-99.

[33] Mazzuca et al. Therapeutic strategies distinguish community based primary care physicians from rheumatologists in the management of osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol. 1993 Jan;20(1):80-6.

[34] Jawad. Analgesics and osteoarthritis: are treatment guidelines reflected in clinical practice? Am J Ther. 2005 Jan-Feb;12(1):98-103.

[35] Hunter DJ. Osteoarthritis management: time to change the deck. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2017;47:370–2.

[36] Riddle, D.L. and Stratford, P.W. (2013), Body weight changes and corresponding changes in pain and function in persons with symptomatic knee osteoarthritis: A cohort study. Arthritis Care Res, 65: 15-22. doi:10.1002/acr.21692

[37] Smith BE, Hendrick P, Smith TO, et alShould exercises be painful in the management of chronic musculoskeletal pain? A systematic review and meta-analysisBritish Journal of Sports Medicine 2017;51:1679-1687.

[38] Luque-Suarez A, Martinez-Calderon J, Falla D. Role of kinesiophobia on pain, disability and quality of life in people suffering from chronic musculoskeletal pain: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2019;53(9):554-559. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2017-098673