The increase in women’s involvement in sports has increased interest in the influences of women’s unique physiology on athletic performance. The effect of the menstrual cycle on athletic performance, is of particular interest. Socially, the menstrual cycle is construed as a time of weakness or inability and often symptoms are dismissed or ignored. Mainstream media encourages women to stop training or change training styles. These psychosocial factors imposed by our society relay strong frailty narratives around a woman’s body and decrease a woman’s likelihood to train. The following data explores where these ideas come from and how drastically these changes are affecting training and performance.

To start, in science we support the null hypothesis (the assumption that there is no difference between groups or conditions) until there is overwhelming evidence to the contrary. Going forward, the null hypothesis we need to reject will be:

There is no reliable difference between the different phases of the menstrual cycle on performance in strength sports.

In order to make broad recommendations to the public about training we need a large clear, concise, repeatable body of evidence indicating a benefit to one phase of the menstrual cycle for performance and training. The following articles will break down the physiology behind why people hypothesize there is a difference between phases and evaluate strength and lifting performance across the menstrual cycle.

A Basic overview of hormones

A hormone is a chemical messenger released from an organ or tissue into the bloodstream to influence organs, tissues, etc. at distant sites. Steroid hormones are derived from cholesterol and are converted through a series of enzymatic reactions to their final form. Once released into the bloodstream, a hormone circulates throughout the body until it binds to a receptor. Receptors can be located inside a cell, on the surface of a cell, and sometimes both. After binding the hormone and receptor complex creates a cascade of molecular, cellular, and genetic effects all resulting in changing physiology. Hormones are measured as a concentration, e.g. how many hormone molecules will likely be found in a certain volume of blood.

The hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis (HPG axis) is the main regulatory pathway for reproductive hormones, which are also known as sex steroids. The sex steroids , estrogen and testosterone, are hormones related to the differentiation of sexual characteristics. The hypothalamus is a specific group of neurons in the brain and one of its many physiological roles is releasing the Gonadotropin-Releasing hormone (GnRH). GnRH binds to receptors in the Anterior Pituitary Gland that result in the release of Luteinizing hormone (LH) and Follicle Stimulating Hormone (FSH). LH and FSH bind to receptors on the ovaries and stimulate the production and release of Estrogen and Progesterone. LH is also important for male sex hormones (testosterone) but that is beyond the scope of this article

These hormones will also act on the tissues that secrete their stimulating hormones in a system called negative feedback. Negative feedback reduces the amount of stimulating hormone that is released, thus the amount of hormone in the bloodstream is regulated by its own concentration. For example, estrogen can bind to receptors on the hypothalamus and the anterior pituitary to reduce the production of GnRH and FSH/LH respectively thus down-regulating their production and in turn down-regulating estrogen itself. This tightly regulated system has the ability to increase and decrease hormone levels depending on external factors and internal cyclical rhythms such as the menstrual cycle.

- Estrogen – Estrogen has 3 subtypes that exert similar physiological effects (ie: estradiol, estrone and estriol) but estradiol is the primary hormone we will focus on in humans. Estrogen binds to estrogen receptors (ER) that are located all over the body. Each of these receptors is located within or on a target cell. When activated this receptor will enact a certain mechanism depending on the cell it’s located in. Estrogen receptors are located all over the body such as in the brain, in the muscular tissue, and on organs. Estrogen is primarily responsible for the stimulation of breast development, female fat deposition and other secondary sex characteristics. Estrogen also has influences on the musculoskeletal system (ligaments, tendons, bone and muscle) thus resulting in the hypothesis that it may influence training performance and outcomes. Further, estrogen is implicated in multiple diseases (cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis, lupus, metabolic disorder, obesity, cancer, endometriosis, uterine fibroids etc.) thus indicating not only the importance of estrogen in the body but the complexity of its action on physiology. Hamilton et al., 2017

- Of note, estrogen doesn’t float around the body freely. Instead, it is bound to proteins like albumin and sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG). When estrogen is bound to, it can be used by the body, but when it is bound to SHBG it is not available.

- Progesterone – Progesterone is released by the ovary. This hormone is responsible for preparing the body for pregnancy. This hormone is actually a precursor for testosterone. Progesterone also has effects on MSK physiology.

- LH – is the main hormone responsible for ovulation. The rapid increase in LH concentration is the body’s signal to release the egg from the ovaries.

- FSH – is also important in sexual development. FSH promotes the growth of the egg in the ovaries before the release of the egg.

- Relaxin – A hormone related to tendon laxity that increases during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle. This hormone is discussed more often in terms of injury reduction. Powerlifting and other gym sports have very low injury risk and thus this hormone is beyond the scope of this article.

There are other hormones that are involved in the development and maturation of the egg during the menstrual cycle, but for brevity, the most relevant hormones are progesterone and estrogen.

The Menstrual Cycle:

Now that we’ve introduced all the main characters, we can dive into the menstrual cycle. The menstrual cycle is a set of monthly changes a woman’s body goes through to release an egg and thicken the endometrium (lining) of the uterus to prepare for the possibility of implantation. The menstrual cycle is broken down into two main phases that are delineated by menses and ovulation. The follicular phase begins when menses (the period) begins and the uterine lining is shed. This is considered day 0 of the menstrual cycle. On average this phase lasts 12-14 days until ovulation occurs. Bull 2019 Ovulation is the release of the egg from the ovary and signals the start of the luteal phase where the body is spending energy preparing for the egg to implant into the lining of the uterus. This phase can last from 10-22 days. These two phases can further be broken down into early mid and late phases to more accurately describe the hormone fluctuations occurring.

The main hormones involved with the menstrual cycle are LH, FSH, estrogen, and progesterone, which fluctuate around 28 days on average, but can range from 18 to 40 days Fehring et al., 2006. Both menses and ovulation are triggered by changes in hormonal concentrations. LH and FSH spike right around the time of ovulation. Estrogen is highest during the end of the follicular phase and the middle of the Luteal phase. Progesterone is elevated through a large portion of the luteal phase.

The menstrual cycle does exhibit a decrease in estrogen levels during the early follicular phase. The reduction in progesterone is also diminished during this time. These are transient changes, and are quite different from the chronic reduction in estrogen and progesterone seen during menopause (more on menopause below).

These hormones have not only local effects on the reproductive system, but their effects also reach systemically via the blood-stream. Between women, there are fluctuations in the concentrations and timing of their hormones and even within one woman there will be changes from cycle to cycle. These individual differences between women are further compounded by the differences in responses women have to these hormone changes. For example, even two women who have the same length of cycle and have similar levels of fluctuation will have different symptoms (muscle pain, headache, bloating, breast tenderness, appetite changes, poor concentration) across the duration of the cycle.

Basal body temperature fluctuates across the menstrual cycle and is often used to track ovulation. Basal body temperature (BBT) is measured when a person gets up every morning. There is a small increase in body temperature around the time of ovulation. This change can indicate ovulation and suggest what phase of the menstrual cycle a woman might be in. Without actual hormone levels being measured, specifically estrogen and progesterone, we cannot determine with certainty which phase of a cycle a woman is in Janse de Jonge et al 2019.

Lastly, menstrual cycles can deviate from the above cited pattern Janse de Jonge et al 2019. Oligomenorrhea (irregular and inconsistent menstrual blood flow) and amenorrhea (absent menstruation during the reproductive years of a woman’s life) are indicators of health issues for women. Riaz et al 2020 Nawaz et al 2020 These health issues are a concern for performance and training and should be managed by a physician (MD or DO).

Due to their systemic effects and varying effects, there is a lot of research investigating effects of these hormones and their subsequent influence on women’s physiology. What is most important to recognize is how these hormone fluctuations actually affect training and performance. This is where the differentiation between statistically significant and clinically significant becomes meaningful. Statistical significance indicates the correlation between two changing variables is likely not due to random chance. Clinical significance is the likelihood that a change in variables results in change in treatment. For resistance training, we would need strong evidence that women reliably see better performance or results with different programming based on specific phases of the menstrual cycle.

The Effect of Exercise on the Hormones of the Menstrual Cycle

There is an idea in many health and fitness circles – particularly where there’s little to no formal training in endocrinology- that your hormones need to be controlled within very narrow “optimal” ranges. Like most things in life, a little bit of truth here, though most hormones tend to have a fairly wide range of normal that the body can adapt to and thrive under due to multiple, redundant mechanisms. In other words, the vast majority of folks will not have clinical symptoms of an abnormal hormonal level unless it’s outside the normal range, which tends to be fairly wide.

The body uses a dynamic process, allostasis, to maintain hormone concentrations by constantly taking in surrounding input and internal changes to modulate hormone levels in the body and keep them within the target range. Allostasis is the body’s process for regulating the internal environment to meet perceived and expected challenges to the internal environment. Another example would be, before lifting weights there will be a rise in blood pressure to help prepare for the imposed demand on the body. The body is adept at this process and estrogen and progesterone are tightly regulated in each person and changes in hormones estrogen and progesterone that do not reliably produce different outcomes are probably not important. When hormone concentrations exist outside of a person’s typical range, and there are clinical symptoms, then an endocrinologist can manage treatment.

In a study with 11 women, 5 self-reporting to be in the luteal phase, and 6 in the follicular phase, researchers found a difference in estradiol concentrations before, during and after resistance training (4×5 sets). During the luteal phase, the subjects had estradiol levels of ~80-136 pg/mL, whereas during the follicular phase women had lower levels of estradiol at 27-34 pg/mL. The luteal phase exhibited a peak in estradiol concentrations 16 minutes into beginning of exercise, which was higher than during the follicular phase Kraemer et al., 1995. These exercise-related findings were reported in another study by Consitt et al, though an additional study reported this finding only during a Calorie deficit. Consitt et al., 2002 Walberg-Rankin et al., 1992

The above data suggests that exercise-induced changes in hormone levels may vary by menstrual cycle phase. However, the regularity of a women’s menstrual cycle may also influence how these hormones change. For example, Nakamura et al. examined women’s hormonal responses to strength training, immediately, 30 minutes, and 60 minutes after exercise. Nakamura et al., 2011 During the mid- luteal phase in women with normal menstrual cycles the resting estradiol and progesterone concentrations were higher than the women with abnormal menstrual cycles. After training, women with normal menstrual cycles in the mid-luteal phase saw significant increases in estradiol and progesterone. In contrast, there were no changes to these same women after training when they were in the early follicular phase. No changes were seen after training in either phase for those with abnormal menstrual cycles.

Despite these reported changes in lab values, none of these studies assessed whether or not the changes in estradiol tended to correlate with differences in strength, hypertrophy, or other training outcomes. Additionally, assessing hormone concentrations during exercise can be problematic, as changes in fluid volume (e.g. from sweating), clearance and metabolism of hormones, and even postural changes, among others, can have a significant impact on these values. Still, if we take the findings of the studies above at face value, we still can’t be confident that they have an effect on performance or training outcomes.

The specific effect of estrogen on MSK physiology

Hormones bind to receptors within their target tissues to produce downstream effects. Estrogen is no different and has three main types of receptors it binds to in order to produce changes in its target tissues

- The ?-ER receptor– Located in the cell’s nucleus, the ? estrogen receptor is found mainly in the mammary glands of the breast, the uterus, ovaries, bone, liver, and adipose tissue. It’s also found in various male reproductive organs.

- The ?-ER receptor- Also located in the cell’s nucleus, the ? estrogen receptor is found mainly in the bladder, ovary, colon, adipose tissue, and different parts of the immune system. It’s also found in the prostate gland of males. Paterni et al 2014

- The membrane estrogen receptor – These receptors are located on the cellular membrane (not in the nucleus) and have been implicated a variety of clinical applications, e.g. recovery from heart attacks, DNA repair in breast cancer, etc. Levin 2013

Each these receptors has the potential to exert effects on a variety of genes and biological processes, many of which are active areas of research. To get a better idea of the what these receptors do with respect to muscular function, we can look at studies where estrogen levels are very low compared to normal.

As discussed in part one of this series, estrogen is mainly produced by the ovaries in females, though a small amount is made by other organs like the liver, heart, skin, and brain. Due to ethical concerns, it is not possible to remove ovaries from a woman for research and look at how muscular function changes. Instead, we can generate hypotheses by looking at animal studies where the ovaries have been removed and human studies in post-menopausal women. In both cases, estrogen levels are very low and thus, can provide insight into how muscular function may change in response to circulating estrogen levels.

Studies looking at ovariectomized rats, e.g. rats that have had their ovaries removed, show decreased metabolic function, increased antioxidant availability, and impaired insulin sensitivity when compared to rats who retain their ovaries. Lowe et al., 2010, Chidi-Ogbulu & Baar, 2019 At the muscular level, ovariectomized rats have decreased muscle cross sectional area and size, have lower rates of muscle protein remodeling and turnover, and recover muscle mass more slowly when the muscles are forced to be inactive. Kitajima & Ono, 2016.

Mechanistically, estrogen may exert its effect directly the contractile proteins of muscle tissue, e.g. actin and myosin. For example, estrogen specifically acts to increase the number of the actin-myosin cross-bridges within the muscle to increase the amount of force generated by each fiber Lowe et al., 2010. Estrogen is also thought to have a protective effect on muscle due to its antioxidant effects specifically on the myosin fiber, which protects the fiber from oxidation that damages the fiber and decreases its force output. Administration of supplemental estrogen to ovariectomized rats restores muscle strength and size to the level of the control rats. Overall, these data suggest the relative importance of chronic estrogen depletion in muscular function in rats, but what about in humans?

During menopause there is a rapid decline and cessation of estrogen and progesterone production, which correlates to a decline in muscle strength that can be reversed through the reintroduction of estrogen and progesterone (Lowe et al., 2010). However, the cause of this apparent reduction in strength is complicated.

At the level of the muscle, post-menopausal women (low estrogen) have higher rates of muscle protein breakdown (MPB) and muscle protein synthesis (MPS) and lower muscle mass than both men and pre-menopausal women with normal levels of estrogen. Smith & Mittendorfer, 2016. These increases in MPB and MPS coupled with reduced muscle mass suggests that either the MPB far outpaces the MPS or that MPS is blunted. Chidi-Ogbolu & Baar, 2019 A recent review indicates estrogen preserves muscle by reducing muscle cell death (apoptosis), which lends support to the theory that MPB is outstripping MPS and causing muscle loss with with chronic estrogen depletion seen in menopause, though not from the acute estrogen fluctuations seen during the menstrual cycle. Collins et al., 2019

Additionally, the chronic loss of estrogen results in a decreased response to training that is not present between men and women before menopause. These chronic reductions in estrogen result in people erroneously correlate the potential effects of estrogen fluctuations alter muscle mass, strength, and other important parameters in relation to training. It’s possible that estrogen has downstream effects on repair processes through proliferation and activation of satellite cells, which associated with muscle growth and hypertrophy are pivotal for muscle gain. Another potential cause of reduced muscle mass in post-menopausal women is the finding that women’s physical activity also decreases across the lifespan. Enns & Tiidus, 2010

Taken together, these data suggest that the large reductions in estrogen seen in menopause tends to negatively impact muscle strength and maintenance. However, it is less clear that relatively small changes in estrogen levels- such as those seen during the menstrual cycle or with hormonal contraceptives- do anything with respect to training outcomes.

Consider that estrogen levels in menstruating women typically range from 32.7-87.2 pg/mL during the follicular phase and 65.4-242.4 pg/mL during the luteal phase, which are ~3x time higher than the average estrogen levels seen during the first 5 years of menopause. which continue to decrease for the remainder of a woman’s life. Anttila et al 1991. This finding suggests that the drop in estrogen during the menstrual cycle would need to be much greater and last for much longer to have the same effect as menopause on muscle tissue.

The data on muscle tissue differences across the menstrual cycle indicate a similar disconnect. Evaluating the difference between muscle protein synthesis rates during different phases of the menstrual cycle shows that there aren’t any significant differences between them. Miller et al., 2006. Additional evidence showing that women and men have similar muscle protein turnover rates throughout young- and mid-adulthood suggest that there is a relatively wide range of estrogen levels that will support health muscular function. Miller et al., 2006 . To further drive this home, women and men respond to training similarly regardless of a woman’s phase of the menstrual cycle. Smith & Mittendorfer, 2016. Overall, the data seems to indicate that these monthly hormone changes are not great enough to diminish women’s ability to maintain muscle protein synthesis across adulthood.

In summary, estrogen does play a role within muscle physiology but the minor changes due to the menstrual cycle within the typical reference ranges are probably insignificant. There are important changes occurring during both menstruation and menopause that can be correlated to changes in muscle strength and muscle protein turnover depending on the stage of life, but do these changes result in actual performance outcome differences. Estrogen does not exert its effects on physiology in isolation. Instead, estrogen is a small piece of the puzzle in regards to physiological functioning and training. Each person has their own hormonal milieu with their own receptor density influencing the rate of binding for hormones. This determines how each person individually reacts to changes in hormone concentration and total availability. These changes are not consistent across the population and there is not one response to training or hormones.

Data on the Effects of the Menstrual Cycle on Performance

The main question is how these menstrual cycle impacts training adaptations and performance. A range of research has been conducted on the effects of the different phases of the menstrual cycle on sports performance as well women’s self-reported evaluation of their own performance. A brief review about phases of the menstrual cycle:

- Follicular Phase: Usually takes place on days 0-14. Begins with shedding of endometrium (menses). Estrogen levels rise gradually throughout this phase, whereas progesterone is low. Body temperature tends to be lower during this phase as well.

- Luteal Phase: Usually takes place on days ~14-28. Begins with luteinizing hormone (LH) surge and subsequent ovulation. Progesterone levels rise through the middle of this phase, then drop. Estrogen levels decrease slightly from LH surge, but are maintained until end of phase, which is marked by the onset of the next menses. Body temperature tends to be higher during this phase as well.

- Average menstrual cycle lasts 28-35 days with 14-21 days in the follicular phase and 14 days in the luteal phase.

Now, let’s take a look at the data

Research by Kishali et al. asked women how they felt during training and competition for 4 sports (Judoka, Taek-wondo, Volleyball, and Basketball). The researchers asked if women took home a medal, what level the athletes competed at, how disruptive athletes’ menstrual cycles were, and how they felt about their performance across the cycle. In this study, women medaled regardless of their menstrual cycle phase and there were no significant differences in performance despite athletes reporting feeling significantly better during the first 14 days of their cycle compared to the second 14 days. Kishali et al., 2006.

A 1996 study set out to test if estrogen affected muscle strength by measuring force production during the follicular phase when estrogen is at its highest. The researchers tested strength in the following groups:

- untrained women not on birth control (12)

- trained women not on birth control (10)

- trained women on birth control (5)

- untrained men (6)

The researchers tested strength by having the subjects smash a transducer as hard as they could between their thumb and index finger at various times during their menstrual cycle. Researchers determined the phase of the menstrual cycle based on the basal body temperature and urine LH test kits. Both trained and untrained women exhibited increases of about 10% from the beginning to the end the follicular phase. Blood plasma estrogen levels were measured in the trained groups, e.g. those taking birth control and those who weren’t, and there were no correlations between the estrogen levels and relative muscle force. Further, the strength performance varied between individuals in relation to the menstrual cycle, though these changes were relatively small in magnitude at ±1.2 lbs of force compared with the 24 lbs of force average. Phillips et al., 1996 c

Another group of researchers measured strength performance, this time in the middle of the cycle, e.g. right at ovulation. The researchers recruited 20 sedentary women; 10 taking oral contraceptives and 10 not taking oral contraceptives. Quadriceps strength and handgrip strength was tested weekly for the length of two menstrual cycles. Cycle phase was standardized based on the number of days since the start of menstruation using a 32 day cycle. Ovulation was predicted to be 14 days prior to menstruation, but was not directly measured. Quadriceps strength was tested using maximum voluntary isometric strength with electrical stimulation to ensure that each woman reached maximal activation. Quadriceps strength was significantly stronger during“mid cycle”, e.g. 12-18 days since the start of the cycle. The significant difference was, at its greatest, 13.5 lbs (or 11.7 %) in untrained women from any point in the cycle to this mid cycle portion. 13.5 lbs in only quadriceps strength may seem like a lot, however the standard deviation within the sample was about 11.2 lbs indicating a high degree of intra-individual variability in strength. Of note, the electrical stimulation ensured that women can maximally engage their muscles during a contraction and that the central nervous system is not inhibiting muscle contraction during a certain phase due to fatigue. Sarwar et al., 1996.

Nevertheless, two out of the three studies reviewed so far suggest their may be a small impact of the cycle phase on strength performance, with strength peaking at the end of the follicular phase as estrogen and LH are increasing. Is this right?

A 2003 study took blood samples from 7 women at the same time of day on day 2 (early follicular phase) and day 21 (mid luteal phase) of their cycle to measure estradiol, progesterone and testosterone levels. Subjects had maximal voluntary isometric force measured by smashing their thumb and index finger together (like Phillips study) on these days as well. No significant differences in strength performance were observed despite relatively large variations in hormone levels, which suggests that strength performance is not directly tied to hormone concentrations. Elliott et al., 2003. Still, let’s not get too misty-eyed about tests on small hand muscles.

Researchers had 19 healthy women with regular menstrual cycles test isometric quadriceps strength with superimposed electrical stimulation, with isokinetic (constant speed) knee flexion and extension strength at multiple angles during different phases of the menstrual cycle. At each day of testing, blood samples were collected to obtain estrogen, progesterone, LH, and FSH levels. There were no differences in quadriceps strength or isokinetic knee flexion or extension strength across the different phases. Additionally, none of the performance metrics had any correlation with the concentrations of hormones. The superimposition of electrical stimulation with the isometric quadriceps strength test ensures maximal contraction of the muscle and removes central fatigue (fatigue moderated by the central nervous system instead of fatigue resulting from a lack of metabolic resources in the muscles) as a confounding variable. This allows for the direct evaluation of the effects of menstrual hormones on strength and indicates that strength changes that occasionally appear in training around the menstrual cycle are possibly occurring because of a different response. Janse De Jonge et al., 2001. Admittedly, this is a small sample size. However, the methods are well controlled and this is good evidence that training is not affected by serum hormone concentrations.

Overall, these studies are only evaluating single muscle or single joint strength when powerlifting performance is dependent on whole body compound coordination and movement. Romero-Moraleda et al examined 13 female triathletes, none of whom were taking hormonal contraceptives. Each athlete completed 1-Repetition Maximum (1 RM) half squat testing on day one and then performed 3 testing days where 20% 40% 60% and 80% of 1 RM half squats were performed at maximal velocity. These testing days correlated with either early follicular, late follicular, or mid luteal phases of the menstrual cycle and the testing order was randomized. Menstrual cycle phase was determined through a combination of temperature, LH urine concentration, and menses. Hormone concentrations were not measured. Peak power, mean power, mean velocity and peak velocity did not differ across the phases of the menstrual cycle. Romero-Moraleda et al., 2019.

A more recent study compared hormone levels to strength performance in 50 women (25 taking oral contraceptives (OC) and 25 who are not) during knee extension, knee flexion, and grip strength. Estrogen and progesterone were collected before the early follicular phase, ovulatory phase, and the mid-luteal phase. The. researchers didn’t find any effect of hormone levels on strength performance, though strength levels were slightly higher in the follicular phase as compared to the luteal phase. Weidauer et al., 2020. The authors concluded that there may be a non-hormonally mediated cause of strength performance differences during different menstrual phases, though additional data is needed to support this hypothesis.

Other Factors Affecting Performance

A number of other factors influencing performance have been identified while investigating the effect of the menstrual cycle on exercise.

For example, Birch et al. examined maximal isometric lifting strength (MILS) of the deadlift at knee height of 10 untrained women. Each woman performed 3 lifts for 3 seconds each and the best one was recorded. There was no differences in MILS between menstrual cycle phases, but there was a ~13 lb difference in strength performance between lifting at 6:00 AM and 6:00 PM. This suggests that there is not an effect of menstrual cycle phase, but the time of day and may have a small impact on strength performance. Birch & Reilly, 2002. Diurnal variations in strength have been established previously, but are likely related to the time people habitually exercise. Vitale et al 2017 Rae et al 2015 Mood is also rarely discussed in research papers on the menstrual cycle but has a significant effect on training Beedie et al., 2000 and may play a role.

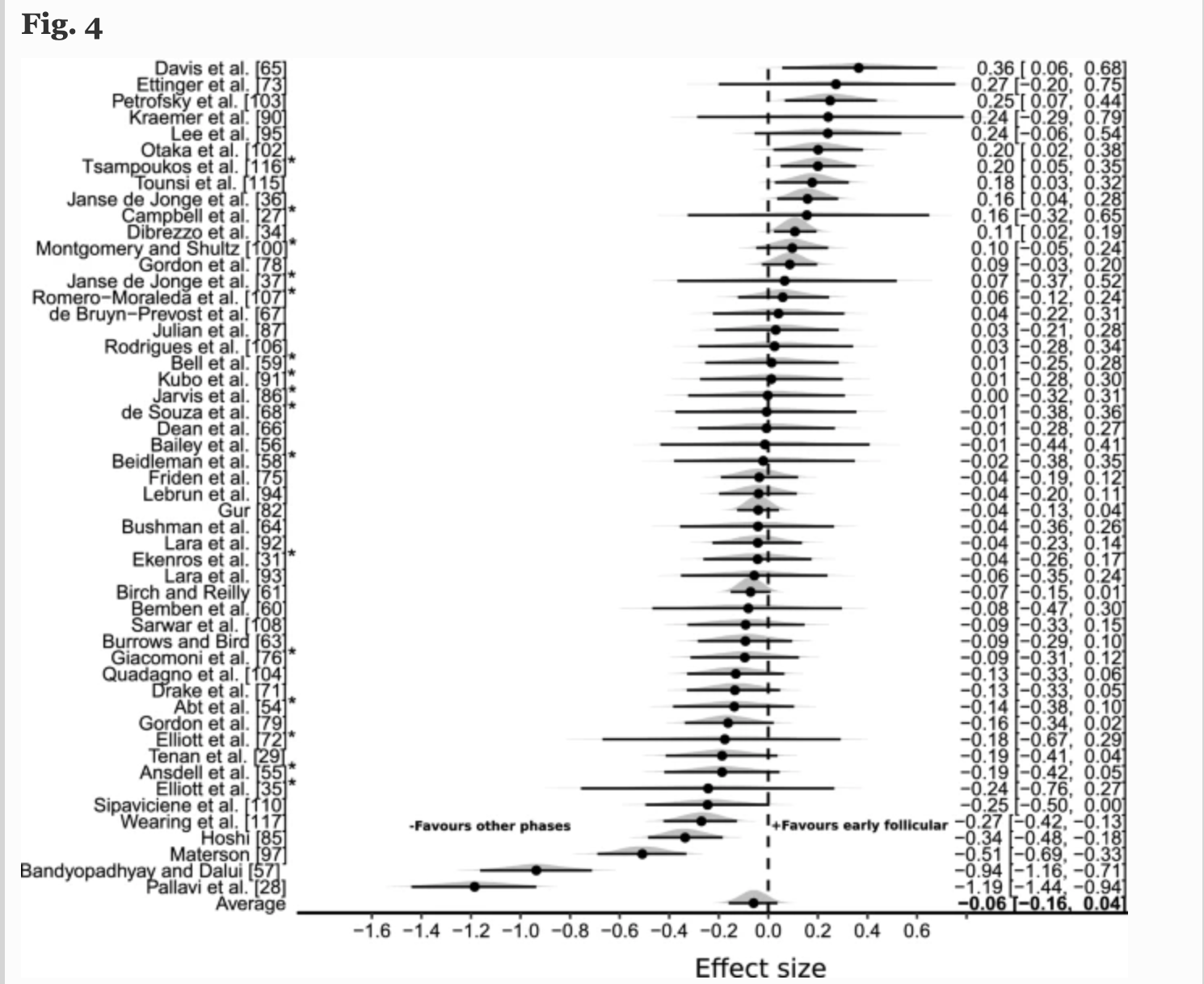

For barbell training and the menstrual cycle, the existing data is limited to proxies like single-muscle force output, half-squats, or similar. There is no consensus for the actual differences in strength sport performance or training adaptations based on the phases of the menstrual cycle due to the lack of data. A review of multiple sports show the variety of effects of responses to different phases of the menstrual cycle. Data towards the right side of the vertical line favors increased performance during the early follicular phase, whereas data towards the left side of the line favors increased performance during other phases. McNulty et al., 2020.

Some of the studies described above do mention oral contraceptives and their effects. Overall, oral contraceptives have a complicated effect on the body because different kinds of oral contraceptives have different levels of hormones (typically progesterone) that make comparison between different pills difficult. Most of the studies seem to show no difference in strength outcomes between those who take hormonal birth control and those who don’t. The dulling of menstrual symptoms has been shown to result in some tolerance to training and a reason for training improvements. Knowles et al., 2019. A recent meta-analysis found that the oral contraceptives may slightly reduce exercise performance in women, but the effects on a group level are very small and the inter-individual variation is wide. Elliott-Sale et al., 2020 This suggests a need for individual management based on an athletes response to hormonal contraceptives. Ultimately, hormonal contraceptives are used for a handful of different conditions such as abnormal uterine bleeding, endometriosis, prevention of pregnancy etc. and one could argue that appropriately managing these have a larger impact on training success than the very small, if any, effect of hormonal contraceptives on exercise performance. As always, this topic is to be discussed between you and your doctor. Remember a baby will be more impactful on your training than any birth control will be.

Throughout this section, we have shown a broad range of responses to strength training across the menstrual cycle. The data presented that do show a difference are not always of the highest quality, as variables are not uniformly measured between studies, don’t always measure actual hormonal variation, and are ultimately not difficult to interpret. Our original hypothesis was “There is no reliable difference in performance between the different phases of the menstrual cycle in strength sports.”

The Science on Periodizing Training Based on The Menstrual Cycle

The evidence that points to differences in training capabilities during different phases of the menstrual cycle has spurred another area of research relevant to female strength athletes. There are four studies that have looked at how changing training based on the menstrual cycle affects strength performance.

Reis et al. compared the maximal strength of 7 untrained women who trained based on their menstrual cycle. For the training protocol, subjects completed 3 sets of 12 reps of leg press 3 times a week during the follicular phase and one time per week during the luteal phase (Menstrual Cycle Triggered Training (MCTT)). The women acted as their own controls, training every third day on one leg and performing the MCTT on the other leg. At the beginning and end of the training they tested strength using the leg press and collected blood samples to analyze estradiol, testosterone, sex hormone binding globulin, progesterone, and cortisol. They found that both groups increased strength and muscle size with the MCTT leg showing greater strength increase than the control leg. Interestingly, the researchers did not present significance levels or p-values for the differences in percent strength gains. Additionally, the MCTT leg has a decreased training load (volume) prior to every testing session which could increase the strength display in the MCTT leg due to reduced fatigue. There also may be issues with assessing strength and size differences between limbs in an individual, as the crosstalk between sides can drive improvements as well. One important outcome of the study was that the authors were (apparently) able to do is implement a strategy to determine what menstrual phase each individual was in. Reis et al 1995 They used body temperature and ovulation strips, which could probably be done at home by individuals wanting to adjust training based on their menstrual phase. Overall, the study shows promise for identifying menstrual phase at home, but the small sample size and confounding variables make it hard to be very confident in these findings without more data suggesting similar findings.

Sung et al recruited 20 untrained women with normal cycles to train each leg according to one phase of their cycle. One leg trained high volume during the luteal phase and one leg trained high volume during the follicular phase. The authors measured muscle strength and size before and after the interventions. The legs that completed the training with high volume during the follicular phase demonstrated a significant increase in strength and muscle size compared to the legs doing the high volume in the luteal phase. Some may take these findings at face value and implement higher volume, lower intensity training in the follicular phase and lower volume, higher intensity during the luteal phase to maximize training adaptations. When looking at the data a bit more closely however, the rate of change in performance is similar in all weeks of the study except for the first and last two weeks of training. It is the initial exposure to training (the first two weeks) and the taper at the end that seem to have fairly large effects across groups. The methodological challenges in this study are potentially confounding the data. Sung et al., 2014 Because the women served as their own control, there is also similar concerns that contralateral strength increases are occurring due to the unilateral resistance training, e.g. crosstalk as described above Munn et al., 2004. To eliminate this potential confounder, we’d have groups of women doing bilateral resistance training using different periodization schemes based on their menstrual phase and see what differences in training outcomes there are, if any.

A 2016 study from Sakamaki- Sunaga et al recruited 14 untrained women to investigate the effect of different programming for different menstrual phases on strength and muscle size. The subjects’ menstrual cycles were determined using basal body temperature and their 1-repetition max dumbbell curl were tested before beginning the training program and then again at 4, 8, and 12 weeks during the study. Training frequency was moderated by the women’s menstrual cycle phase, either luteal or follicular. Researchers used subjects as their own comparisons and had them train both arms differently. One arm trained high volume (3 times a week) during the follicular phase low volume during the luteal phase (1 time per week) and the other arm trained high volume during the luteal phase and low volume during the follicular. Women did significantly increase their elbow flexor cross sectional area and strength from baseline. The researchers found no differences in muscle size or strength differences between the two arms indicating that training load based on the menstrual cycle does not significantly increase strength or cross sectional area. Sakamaki-Sunaga et al., 2016 Again, the methodology raises concerns over the applicability of varying unilateral training protocols to more traditional resistance exercise programming.

In a 2017 study by Wikstom-Frisen et al., 59 resistance-familiar women (32 on oral contraceptives and 27 without oral contraceptives) were split into 3 groups:

- Group 1 (follicular phase training): high frequency training (5x/week) during the first two weeks of the menstrual cycle and low frequency the second two weeks (once per week)

- Group 2 (luteal phase training): low frequency training (1x/week) during the first two week and high frequency training (5x/week) during the second two weeks of the menstrual cycle.

- Group 3 (control): trained 3x/week during the whole menstrual cycle.

The study period lasted 4 months and the following outcomes were measured before and after the training interventions : squat jump (ST), countermovement jump (CMJ), isokinetic peak torque and LBM were collected for each of the groups. Groups with higher volume during the follicular phase (Groups 1 and 3) had increased ST, CMJ, and peak hamstring torque but not quadriceps torque, while training with higher frequency during the luteal phase did not result in increases. While this looks like Group 1 got better than Group 2 during the course of the training, each went into the post-testing at different points in their training cycle. Group 1 entered into their training cycle on a week where they had completed 5 training sessions, Group 2 entered into testing on the week where they completed 1 training session, and Group 3 had 3 training sessions the week of testing. Wikström-Frisén et al., 2017 There appears to be an effect of volume the week of testing, the follicular phase training group only trained 1 time and the relative decrease in volume may have acted like a taper while the luteal phase training group had high volume. These differences in volume the week of testing might be confounding these results and again is not clear evidence of a training effect.

In these four studies on periodized training, there is weak but converging evidence pointing to a benefit of periodized training with some limitations in the methodology. Performance potential will vary day to day based on biological, psychological, social, and environmental inputs. The small performance differences that are seen in these multi-week studies don’t necessarily persist over many years of training and may be absent in larger sample sizes. Long term, the rate of strength gain is dependent on many more factors than just training during the menstrual cycle. Existing evidence on training response indicates that individuals will vary greatly in their response to training. Ahtiainen et al 2016 . Some variation or noise in training may be due to menstrual symptoms, possibly due to central fatigue, but most likely not directly influenced by hormone levels. To determine if there are additional effects of the menstrual cycle and specific periodization techniques on inter-individual training responses, we need strong evidence.

Another important drawback of these studies is that none actually measured hormone levels. Not every woman has a 28 day cycle Fehring et al., 2006, there are variations in hormone timing and concentration from cycle to cycle. Menstrual cycles vary between women and vary additionally with age and BMI. Bull et al., 2019, Fehring et al., 2006 Many of the aforementioned studies assumed a 28-day cycle and thus it isn’t possible to know if women were training or testing during the correct phase during the studies. Hormone ovulation sticks are capable of signaling ovulation and thus determining cycle phase, luteal or follicular, but breaking this down further to early, mid, and late is more complex and would require daily analysis of exact hormone concentrations. Many women don’t have the time or financial availability to measure their hormone levels to know exactly what phase of their menstrual cycle they are in. Doing so is probably excessive, as we have seen in previous articles hormone concentrations do not correlate with performance. This is particularly relevant for team sports athletes. These athletes are more likely to be lumped with a large group that trains together, and while some women might have similar cycles, it is probably best to train according to the competition schedule, and to train together. The best training is going to be consistent and utilize progressive overload based on competitions.

Additionally, the studies reviewed used small sample sizes of women with methods that may not be generalizable, e.g. the different unilateral training protocols. This makes it difficult to be confident that the results are meaningful and should be used to influence coaching practices. One strategy we can use to overcome the small sample size issue is to pool these studies together via a systematic review and meta analysis and see if there are differences in performance and training responses across the menstrual cycle.

Multiple recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses agree there is inconclusive evidence that the hormonal changes occurring during different menstrual cycle phases have an effect on training response or performance. Blagrove et al., 2020; McNulty et al., 2020; Thompson et al., 2020 Carmichael et al., 2021. Unfortunately, the majority of the evidence is of low-quality, which limits the ability to find a consensus. McNulty et al., 2020.

Taken together, it’s probably best to avoid making prospective changes to a training program based on menstrual-phase-related hormone fluctuations while monitoring an individual’s response to the training and adjusting as needed. Anecdotes in these situations are useful to exemplify the range of responses to the menstrual cycle women have specifically as it relates to training. However, one woman’s experience is not another’s diagnosis. Women are resilient and they will overcome a range of obstacles and be highly successful athletes regardless of the phase of their menstrual cycle. Women should continue to train in a way that promotes their independence through consistent, auto-regulated, and progressively loaded training.

Discussion:

At the beginning of this article series, we set out to see whether or not the existing scientific evidence rejected the hypothesis that there is no reliable effect of the different phases of the menstrual cycle on performance in strength sports. Based on the above evidence and the previous articles, there are 4 main reasons we cannot reject this hypothesis and therefore we accept it:

1) There are not reliable or repeatable cycle phase induced differences in training adaptation or performance or compound movement performance. Fluctuations in estrogen observed during the menstrual cycle do not tend to have a robust effect on training performance, or adaptations in strength training. While they may exert some effect, these effects are either too small or too unreliable to characterize, particularly in comparison to physiological parameters (age, training status etc.), and environmental factors all work in concert to alter adaptation to training.

2) There is a high degree of inter-individual variability in response to cycle phase, contraceptives, and training. Women have high inter-individual variability between menstrual cycles and intra-individual variability between women. Women respond to training with a heterogeneity of responses. Training should not automatically start at a lower intensity, frequency, or volume at the start of the luteal phase. Women have reported a range of increases and decreases in their performance variables across the menstrual cycle. The use of an auto-regulated program and consulting with a coach is the best way to ensure consistent progress.

Coaches should be comfortable with what a menstrual cycle is, and the physiological processes occurring across the cycle. If you have made it this far you probably are now well-versed. A coach’s main job in this situation is to support the athlete they are working with and help them troubleshoot. A good coach will interpret outcomes and determine patterns in training, if present, to meet you where you are, which is going to be more efficacious than automatically planning based on the menstrual cycle. An athlete should not be in severe pain or discomfort during training, nor should there be a complete deload based on menstrual cycle symptoms. Coaching requires developing a strong relationship with an athlete and sometimes that includes talking about healthcare topics.

3) Other inputs on performance/adaptation are seemingly more reliable, more important, and more modifiable than altering training based on cycle phase. Time is best spent focusing on proper sleep, nutrition and training that is appropriately programmed via adjustments in volume, intensity, exercise selection, frequency, etc. in order to drive fitness adaptations without outstripping recovery resources.

Symptoms of the menstrual cycle may have an impact on training, however these symptoms tend to be unique to the individual, vary within individuals, and learning to work with them will serve athletes in the long term. Start training, stay training, and don’t be discouraged by small setbacks that happen from week-to- week. Overall, athletes are human first, female second; there are a range of fluctuations experienced in life and training that have a greater chance of changing outcomes than the menstrual cycle.

4) Accurately tracking and managing training based on cycle phase has costs ($$ + potential nocebo). Tracking training accurately with serum hormones is costly and ultimately challenging to complete. Telling female athletes her cycle is changing her training may be potentially harmful based when coaches and subject matter experts seed negative expectations within individuals. This sets the individual up to have negative expectations and through training may be more likely to fulfill those negative expectations, which may have downstream effects pertaining to long-term training adaptations.

Conclusion

Overall, being physically active and reducing the barriers to physical activity is far more important than the menstrual cycle; by telling women they need to periodize their training based on their period, we are actually creating barriers by complicating training. These barriers reduce the likelihood that a woman will train. The goal should be to optimize the variables that will provide the greatest outcomes, which includes consistency and well-designed training programs utilizing progressive overload. Focus on getting to the gym and strength training at minimum twice a week to meet the WHO guidelines of physical activity.

Barbell Medicine University Hoodie - Black/Yellow, Large

Barbell Medicine University Hoodie - Black/Yellow, Large