The ability to engage in physical activity is an integral component of the maintenance of health and independence with age. This capacity is typically developed through increased activity, either through manual labor or deliberate exercise. Current recommendations for physical activity vary by age group, with adolescents recommended to engage in at least one hour of moderate-intensity physical activity daily and 3 days per week of muscle strengthening activity. Adults are recommended to engage in 2.5 to 5 hours of moderate level physical activity a week and at least two days per week of strength training. [2] Dankel et al found that only 18.6% of individuals in the United States are meeting the guidelines for muscle strengthening. [3] According to the most recent survey of Europeans, 65% of this population is inactive physically.[4] The population at large is falling far short of current recommendations, with typical reasoning related to a lack of time, confidence, and motivation.

Key Points

- The motivation to train, or participate in physical activity is multifactorial but highly related to the autonomy and enjoyment we gain from participation.

- The coaching language and environment can promote a supportive or thwarting environment that has repercussions on an athlete’s long-term participation in physical activity.

- The achievement of basic psychological needs of autonomy, competence, and relatedness are integral to individuals’ continued desire to participate in physical activity.

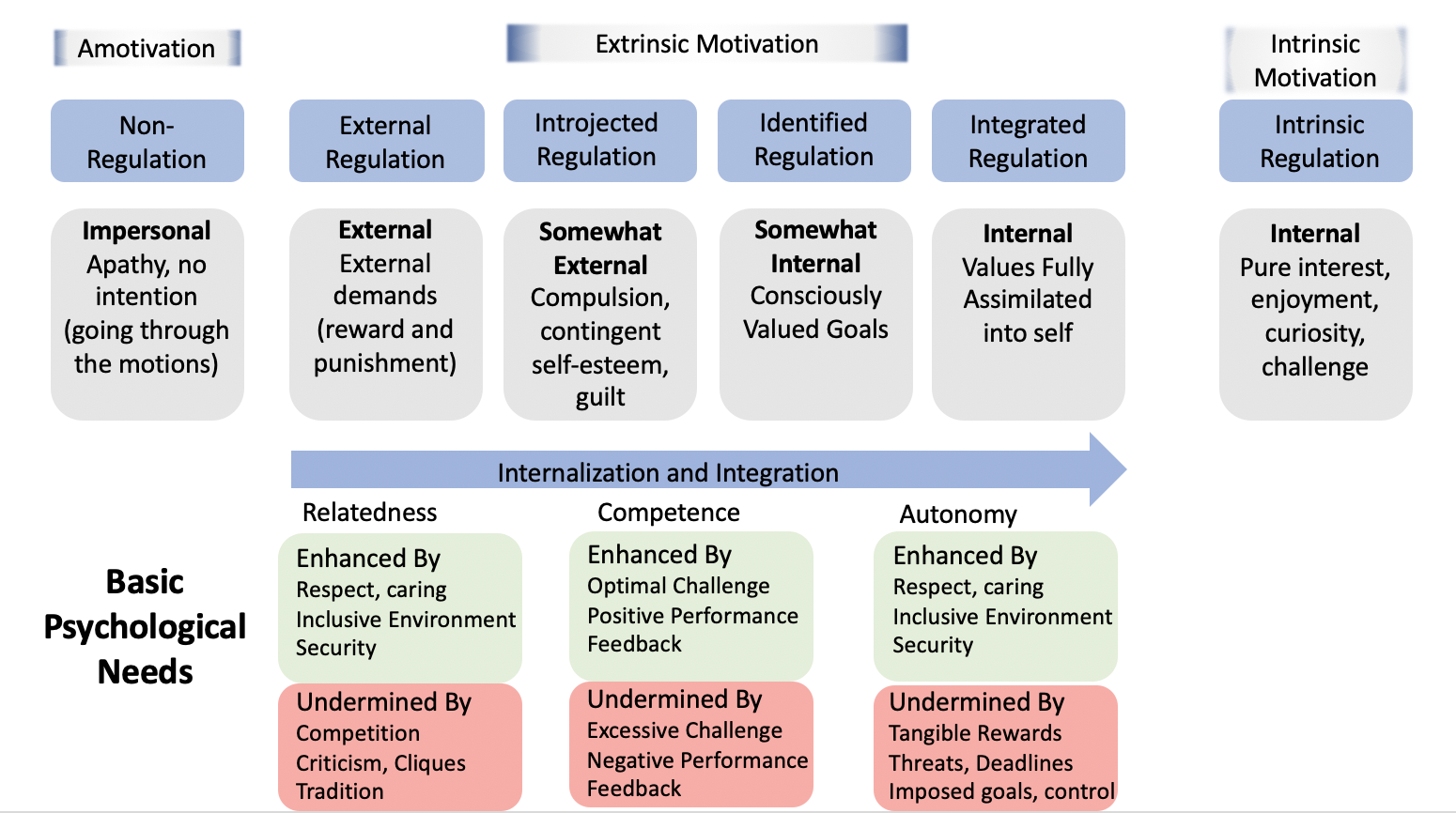

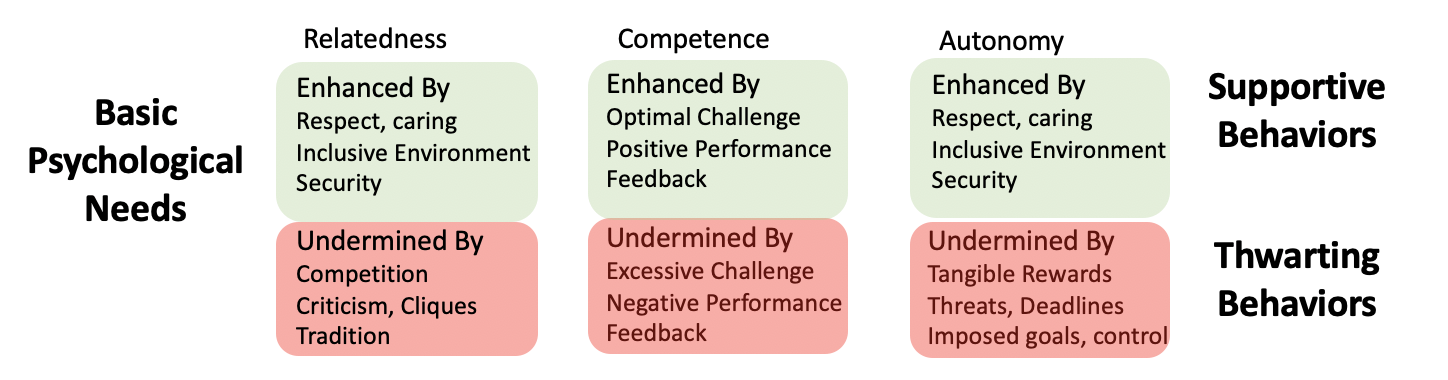

There is a substantial amount of research on the role that motivation plays in physical activity. [5] Much of this research is framed through the Self-Determination Theory (SDT) as it examines the impact of motivation on emotional, cognitive, and behavioral components of exercise.[6]The theory purports that motivation is comprised of intrinsic and extrinsic components. Intrinsic motivation leads people to act purely to satisfy their own curiosity or desire for mastery. Extrinsically motivated factors are all driven by social values and are often self-determined as values become integrated and internalized. The three main domains are feelings of relatedness, competence, and autonomy. [7]

Relatedness, competence, and autonomy comprise the basic psychological needs (BPN) of humans with each contributing to the overall magnitude of self-determination to different degrees. Autonomy is the opportunity to feel in control of one’s actions and is promoted by providing opportunities for choice, acknowledging choice, avoiding judgement, and encouraging personal responsibility for actions. The role of these judgemental assessments will be further explored in the “why this study matters” section. Competence is facilitated by an environment in which the optimal challenge is encountered and by feedback that promotes self-efficacy. Relatedness is promoted by environments that foster respect and mutual caring.

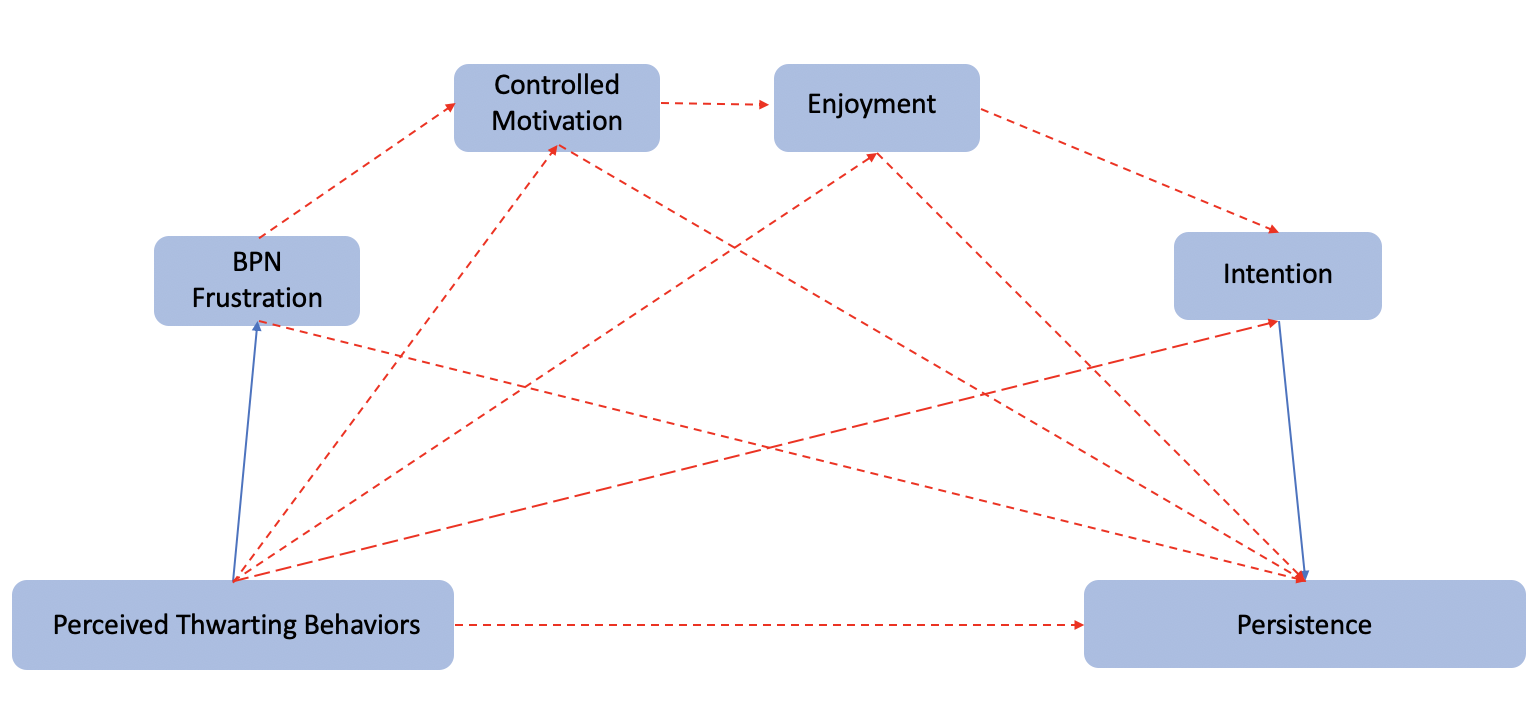

Under this model, Vallerand proposed the Hierarchical Model of Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation (HMIEM) to explain how global, contextual, and situational factors are responsible for an individual’s behavior. [8] Here, social factors affect different types of motivation depending on how BPNs are met. These social factors are often dichotomized into a bright side and a dark side with the bright side being factors that facilitate adaptation towards intrinsic motivation (satisfaction) and the dark side being tenets that are related to psychologically controlling and frustration of needs (frustration). The HMIEM has demonstrated both cross sectional and longitudinal evidential support. [9-10]

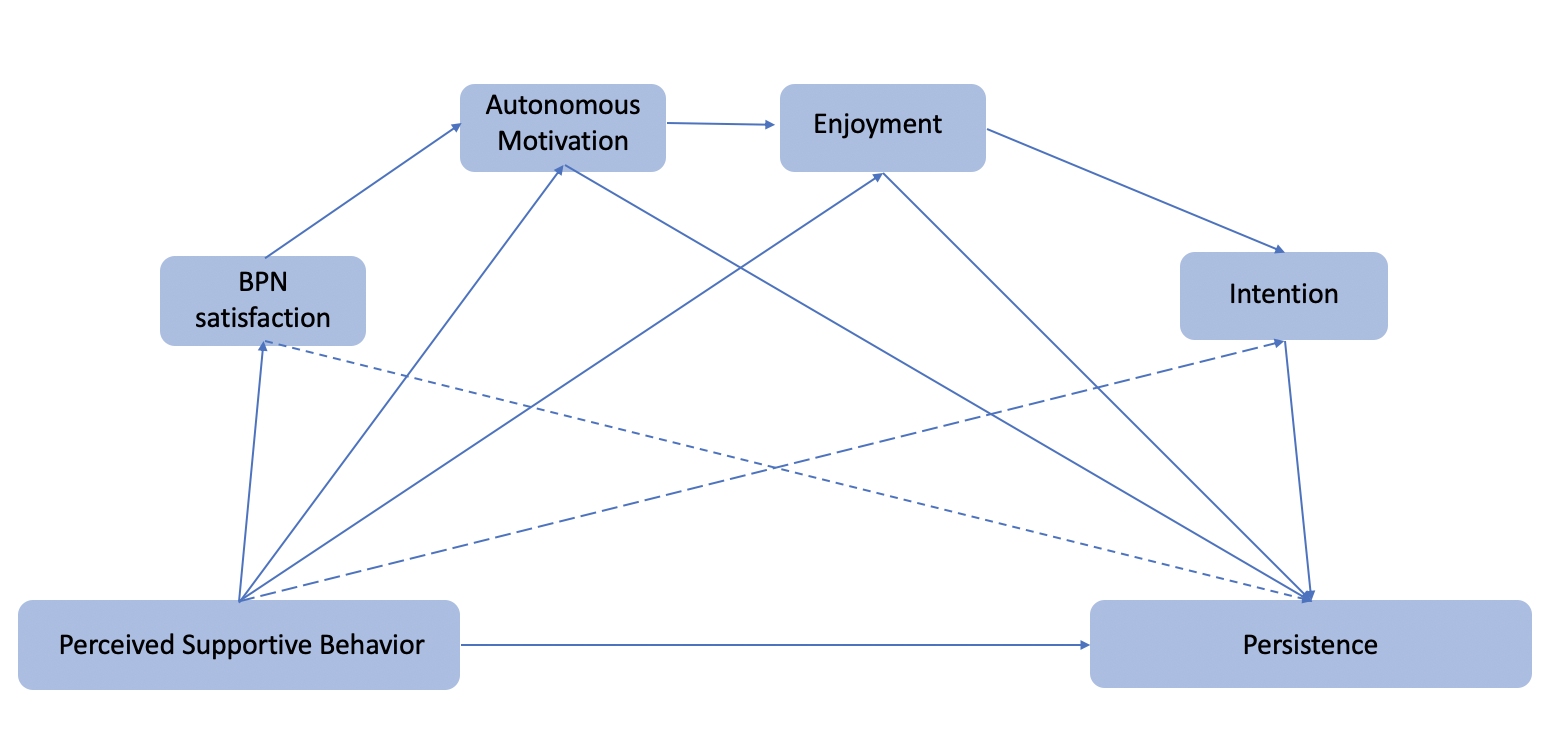

The model explains how perceived interpersonal behaviors from others will determine either satisfaction or frustration with BPN. Specific to exercise, settings where BPN is positive are related to autonomous motivation (participation because they value the activity). Where it is negative it is associated with controlled motivation (participation either for an external reward or guilt). When it comes to discussions regarding training or rehabilitation, messages that seek to facilitate positive settings where individuals value the activity at hand, not settings where they feel they need to perform an exercise or they will be in pain, or that they need a specific technique or they will suffer an injury seem to be more effective.

Exercise enjoyment is a large influence on the intention to continue exercise. It drives feelings of autonomy where individuals demonstrate a higher intention of continuing to exercise in the future. [11-12] Azjen has reported that enjoyment is, in fact, the most proximal determinant of whether an individual will continue exercise participation. [13] This should likely be stating the obvious, but if clinicians are to expect individuals to continue training and participate in exercise, an environment that fosters independence, challenges individuals, and promotes autonomy will increase the likelihood of this transpiring. If framed through the entry point to begin exercise, it needs to be constructed in a manner that is not intimidating. Unfortunately, many of the paradigms for resistance training are predicated on narratives around the need for perfect form and movements causing injury.

Journal Club

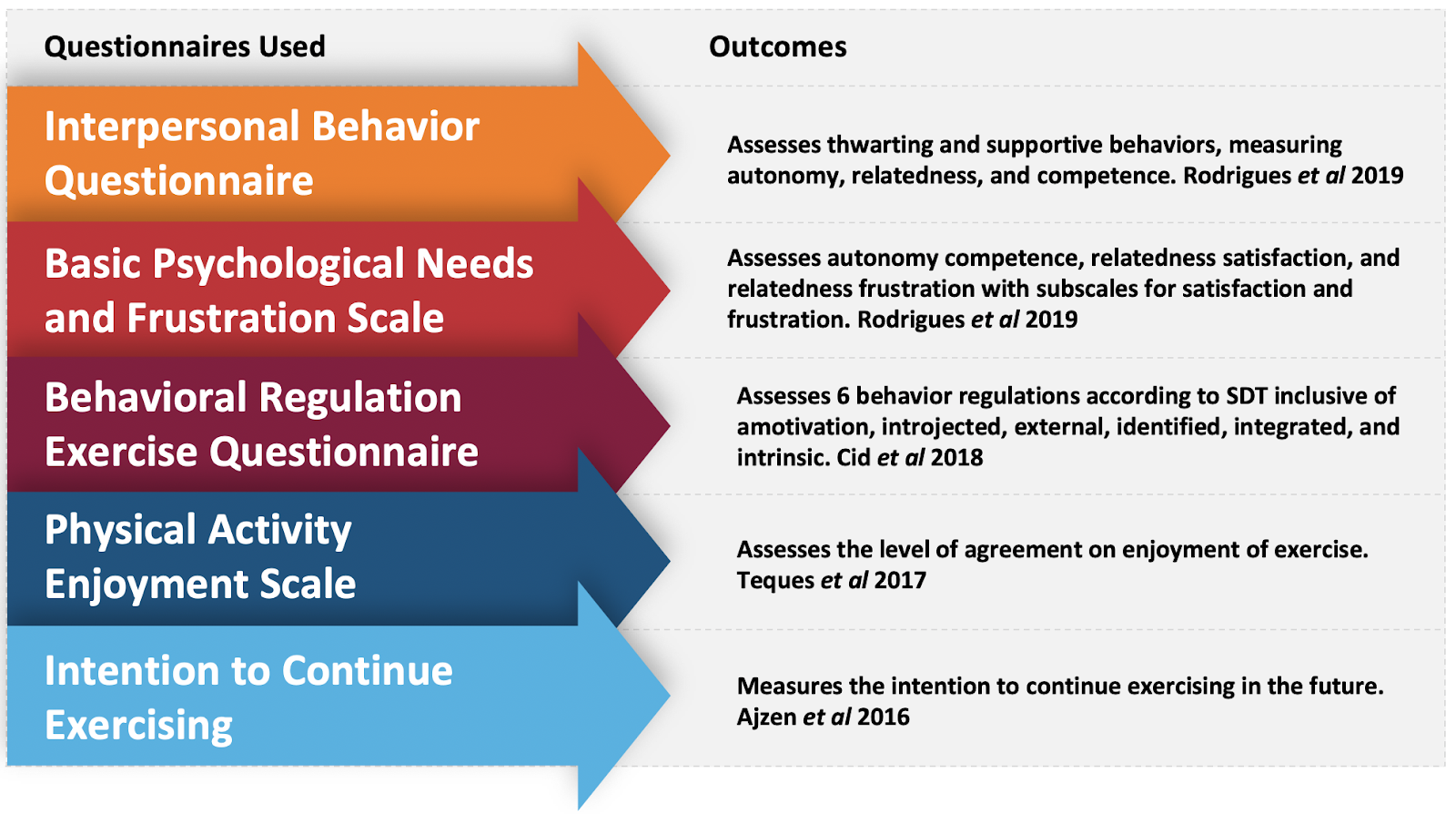

To explore this question further, we turn to a recent paper from Rodrigues et al. titled “The bright and dark sides of motivation as predictors of enjoyment, intention, and exercise persistence.” [1] The purpose of this study was to analyze the relationship between the motivation to exercise and enjoyment, intention, and adherence.

Methods

The study consisted of 575 gym members aged between 18 and 65 years old (mean=34.07, SD=11.47). All participants had at least 6 months experience attending the gym. Training frequency was determined by self-report with a mean of 3.52 days/ week (SD=1.28) with sessions lasting a mean of 61.54 minutes (SD=17.64). Gym members were recruited at random time points throughout the day at the reception desk of the facility. Informed consent was obtained to aggregate data of gym usage and subjects were asked to fill out a survey regarding motivational determinants, enjoyment, and intention. Their exercise adherence was then tracked for 6 months using data from gym attendance records.

The researchers then tracked subjects’ exercise adherence over 6 months based upon the computer system at the gym, comparing their frequency of exercise to the self-reported frequency of exercise at the beginning of the study. This was coded as either a “0” or “1” with zero constituting participants who quit or those whose attendance was significantly different than self-report. Coding for a “1” meant that subjects maintained their self-reported level. There were two assumptions regarding adherence 1) individuals who exercise regularly for more than 6 months have lower intention to drop out, 2) individuals who have exercised less than 6 months have an approximately 50% drop out rate.

Participants with greater than 5% of data missing were excluded from analysis. Data was processed using SPSS with mean, standard deviation, bivariate correlation, and composite reliability calculated for all variables. The authors then conducted a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to test psychometric properties of their model and a structural equation model (SEM) was performed to test model fit.

The authors did conduct a power analysis using G*Power v3.1 to determine adequate sample size. The parameters followed were f2=0.01, ?=0.05, and statistical power of 0.95. [14] Under those parameters a minimum sample size of 287 participants was needed.

The authors then performed a serial mediation analysis to understand the mediator’s role on outcomes according to the recommendations of Hayes et al. [15] This is used when multiple mechanisms are proposed to connect the dependent to independent variable. The author’s developed two models, one for the bright side of motivation and one for the dark. In model I, thwarting or opposing interpersonal behaviors, BPN frustration, and controlled motivation were seen as specific path covariates. Model II was the same approach, but using bright side constructs. The authors also elected to perform a multi-group analysis between male and female participants to look at between group characteristics.

Results

Of the 575 participants in the study, 472 (82%) exercised a mean of 2.89 days/week (SD=0.98) during the 6 months of data collection. The other 103 participants discontinued exercise within the first 2-4 months of data collection. Bright side motivational constructs were positively correlated with each other, as well as enjoyment, intention to continue exercising, and exercise persistence.

The authors then performed a confirmatory factor analysis to test whether the measures of constructs are consistent with the researcher’s understanding of the nature of the construct. In this instance, how much the researcher’s proposed model fits the data. The authors did achieve convergent and discriminant validity that was above what was considered acceptable. Enjoyment was the variable with the highest indirect effect on exercise persistence. The only constructs that were not positive were perceived supportive behavior on BPN satisfaction, perceived supportive behavior on BPN frustration, and perceived opposing behavior on BPN satisfaction.

A serial mediation analysis was then performed in an attempt to explain the mechanism by which different constructs influence exercise persistence. Two models were constructed, one for supportive behaviors and one for opposing behaviors. For supportive behaviors, enjoyment once again presented the highest effect on exercise persistence (?=0.83). Prior to that in the model, autonomous motivation had the largest effect on enjoyment (?=0.85).

In the model related to opposing behaviors, the path between enjoyment and exercise persistence demonstrated a significant effect (?=0.83). The path between intention and exercise persistence also had an effect (?=0.04). Here, a lack of enjoyment and intention were related to discontinuing exercise.

The results of multi-group analysis demonstrated adequate fit for both male and female subgroups and no difference between the two.

Take Home Message

It likely comes as no surprise to the reader that the degree to which someone enjoys an activity is related to their desire to continue that activity. This seems like an obvious relationship but it does require some reflection on what that means for trainers and clinicians in the way in which they facilitate participation. The basic relationship between either perceived supportive behaviors or perceived opposing behaviors and exercise persistence seems obvious, but as with most relationships, there is a high degree of nuance to what can influence the outcome.

If the goal is to facilitate autonomy, an inclusive environment where individuals feel respected is ideal. Once again, this seems like common sense but when looking at common narratives to which individuals are exposed, the opposite often holds true. A large portion of readily available information states that moving outside of a preset norm will increase one’s risk of injury. This would seem to fall in the category of an opposing behavior as it could readily be interpreted as a threat, and imposes an arbitrary goal of what movement should look like. Both in individuals in pain and those without, there are beliefs that certain movements such as lifting with a rounded back are dangerous. [17-18] There is ample evidence that individuals obtain these beliefs from healthcare providers and that within the profession there is an implicit bias that lifting with a rounded back is bad. [18] It is difficult to be surprised that there is an epidemic of inactivity in society when individuals who are charged with being promoters are advocating that if an individual is moving wrong they will hurt themselves.

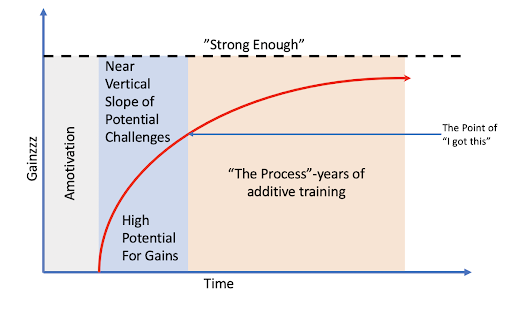

If the expectation is that an individual needs perfect form from the start, this positions an anchor that is likely unachievable by most individuals. There is a large bolus of evidence exploring the relationship between the anchor (e.g expectation) and the target (e.g. activity) and the role that the distance between the two plays in an activity being assimilated dating back to the 1950’s. [19] The ultimate goal is to keep the anchor and the target close so as to facilitate the perception of progress. Doing so will help to increase an individual’s perception of competence with a task.

The IBQ used as an outcome measure in the current study assessing traits of competence via questions such as “my exercise instructor encourages me to improve my skills.” This should be the goal of all instructors but opposing behaviors can manifest if individuals send a message that participants will likely fail. A conversation of what constitutes failure then must transpire. Many instructors are likely unaware of the messaging they send by correlating bad form of technique to injury. In the initial phases of learning any activity, the rate of error is going to be high. We often forget that the messages we send out are seen by a wider audience than those with whom we interact. Many novice individuals are exposed to different varieties of exercise via seeing individuals performing at the highest level and comments such as movement deviations short deviations from perfection will expose that athlete to increased risk of injury. Now the novice athlete has anchored the expectation to a likely unattainable goal and an expectation has been set there is a high level of risk in undertaking the activity. This does not facilitate competence in an individual and likely turns what is a well intentioned supportive behavior into a opposing one.

The third principle of BPN, relatedness, is where I would argue resistance training has the most potential for facilitating a supportive environment compared to other training modalities. The beauty of resistance training in particular is that all levels can participate in the same room. If one is to go out and train for an endurance sport with peers, they need to be surrounded by peers of the same level or they will be training alone. There are obvious exceptions to this with the rise of spin classes but resistance training is unique in that an individual performing a deadlift for the first time can train next to an individual lifting 4x bodyweight and still be part of the inherent training community. This is not to say that barbell training is the best means with which to train an individual. The best means is the one which that particular individual enjoys, can see progress, and in which they can be consistent. This is an area where I must concede as a clinician I have made mistakes in the past. There are exercise modalities that I had deemed either not effective, harmful, or borderline ridiculous in the past. As a result, I advocated against participation in those sports or types of training. This has changed over the last years as evidence continues to emerge on the level of inactivity in the general population. Prior to discussing what training modality is the most effective at this junction we likely need to advocate that individuals realize that almost all active training is more effective than nothing at all.

All of this fits into the overarching construct of SDT and the need to promote an intrinsic motivation to be active. An interesting paradigm emerges here as the benefits of activity are often not immediately apparent. One session of training does not elicit results, it is the summation of activity over time that leads towards mastery. Even this is an asymptotic curve as the more trained and individual becomes, the harder gains are to obtain. At some point, the task is no longer seen as an obstacle, but rather a behavior. There are no 30 day “fixes” or 8-week training programs that yield long term results. Long term results are obtained from long term training and are maximized by an inherent motivation on the part of the individual to improve. An issue here is there does often need to be a progression through amotivation to extrinsic motivation prior to intrinsic motivation manifesting.

A common theme of the SDT model worth expounding upon is the role of rewards in the movement through extrinsic motivation. While it seems intuitive that rewards would increase motivation, there is evidence that they undermine autonomy. [7] In the rehabilitation realm specifically, this raises concerns on how certain interventions are framed. There is often the case made that passive modalities, lacking efficacy, can be used as a means to “bridge the gaps” or “increase buy-in” from patients. These modalities could easily be construed as a reward, detracting from the overall purpose of the treatment. If there is the message that a person needs an intervention, especially one that lacks solid efficacy, it can inhibit intrinsic motivation. A meta-analysis on rewards undermining intrinsic motivation by Deci et al concluded in it’s summary:

“There is substantial support for the general hypothesis that expected tangible rewards made contingent upon doing, completing, or excelling at an interesting activity undermine intrinsic motivation for that activity.” [20]

In lay terms, creating rewards predicated on someone performing an activity decreased motivation. If this is the case, telling individuals that they should perform an exercise, or more so they need to perform it perfectly can decrease intrinsic motivation. It could also be stated that telling an individual they need tape, needling, scraping, glitter (all interventions with the same level of evidence) could decrease motivation. I want to be clear here as well, that the same could be said for informing an individual that they need to lift with a barbell. What is more important is that they find a type of physical activity that they will be motivated to perform consistently.

The nature of the motivation and subsequent performance are often influenced by external influences. The individual who exercises for fear of experiencing poor health is motivated differently than the individual who exercises to live their life in optimal health. These individuals are also different from the individual who exercises with the goal of breaking world records. Three distinct anchors emerge for each scenario with two, avoidance of poor health and breaking world records, likely creating large gaps between the expectation and action.

This is why external regulation, acting only to earn rewards or avoid punishment, is the lowest level of extrinsic motivation. The process, as it were, is still predicated on outside factors. The next phase, introjected regulation, are actions based on the enhancement of pride or self-esteem/avoidance of guilt or anxiety. Likely many individuals have experienced the phase where they feel bad about not training. Here, personal responsibility begins to manifest in its lowest form as self regulation has been partially internalized but has not yet become a personal goal. It is being able to begin the transition between introjected and identified regulation that is an important step as here, the goal of training begins to be seen as useful. The transition here is why framing is so important to advocacy in physical activity. If we are teaching movement as a means of avoiding pain, the overall approach is likely flawed. There was also an intentional distinction in the prior sentence regarding movement vs. exercise. For many individuals, exercise is already seen as a punishment or something they have to do, yet movement is easily framed through something that needs to take place in order to maintain independence in life.

The last step of extrinsic motivation is integrated regulation, where the external influences have started to become part of one’s personal identity. Almost like waking up and going to put on the coffee, this is where physical activity just becomes something that an individual does. There is no reason that being physically active, or being able to move should not be part of the average individual’s identity. Yet, coaches and rehabilitation specialists often tell people that they should not move a certain way, or that basic, everyday tasks will wear out some arbitrary joint. We have gotten to the point now where there is even messaging that idle tasks such as sitting are comparable with behaviors known to cause cancer. How can we expect the normal population to feel autonomous and competent when the messaging is setting a trap with every activity if not properly evaluated by a trained individual?

The individuals in the current study were already going to the gym under their own volition. There was still a relationship between their intention to continue exercising and their predisposition with which to do so. In the rehabilitation frame, it is often said that certain exercises are needed with which to address certain issues, yet exercise as a whole does not offer large effect sizes for the treatment of many issues.Saragiotto 2016, Zacharais 2014 The reason why individuals need to move and exercise likely needs to be discussed in terms of messaging if we are to progress beyond amotivation or external regulation. Individuals need to perceive the benefits of exercise as it relates to their long term health and find value in the exercises they undertake. Clinicians and trainers can facilitate this by implementing supportive language to meet individuals basic psychological needs.

The Self Determination Theory Model is complex, but human behavior is complex as well. If those of us advocating for increased participation in physical activity want to be more effective, we need to embrace this complexity. There is not one right answer when it comes to either the style of motivation or the exercise selected for all individuals. We need to meet the individual where they are at, whether it be amotivation or better anchoring of expectations to intrinsic motivation. We belabor the point that words matter at Barbell Medicine but studies such as this make it readily apparent. The language we use in our communication can have a profound effect on people’s willingness to engage in activity as well as their willingness to continue after we are no longer around. We need to facilitate competence in our athletes and show them what they are capable of on their own. I use athlete here as a synonym for individual to close in this piece as everyone has the potential to identify as an athlete, most of them just need some help along the way.

References

- Rodrigues F, Teixeira DS, Neiva HP, et al. The bright and dark sides of motivation as predictors of enjoyment, intention, and exercise persistence. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2019 Dec 19.

- Piercy KL, Troiano RP, Ballard RM, et al. The Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. JAMA. 2018 Nov 20;320(19):2020-2028.

- Dankel SJ, Loenneke JP, Loprinzi PD. Dose-dependent association between muscle-strengthening activities and all-cause mortality: Prospective cohort study among a national sample of adults in the USA. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2016 Nov;109(11):626-633.

- EC. Special Eurobarometer 472 – Sport and Physical Activity.2018;1-133.

- Knittle K, Nurmi J, Crutzen R, et al. How can interventions increase motivation for physical activity? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Psychol Rev. 2018 Sep;12(3):211-230.

- Ryan R, Deci E. Self-determination theory. Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development, and Wellness. New York:Guildford Press; 2017.

- Cook DA, Artino AR Jr. Motivation to learn: an overview of contemporary theories. Med Educ. 2016 Oct;50(10):997-1014.

- Vallerand R. Toward A Hierarchical Model of Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation. Adv in Exp Social Psych. 1997 29:271-360.

- Standage, Martyn & Duda, Joan & Ntoumanis, Nikos. (2003). A model of contextual motivation in physical education: Using constructs from self-determination and achievement goal theories to predict physical activity intentions. Journal of Educational Psychology. 95. 97-. 10.

- Gillet N, Vallerand R, Amoura S, et al. Influence of coaches’ autonomy support on athletes’ motivation and sport performance: A test of the hierarchical model of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. Psych of Sport and Exercise. 2010 Mar;2(11):155-161.

- Ntoumanis N, Thøgersen-Ntoumani C, Quested E, et al. The effects of training group exercise class instructors to adopt a motivationally adaptive communication style. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2017 Sep;27(9):1026-1034.

- Hagger MS, Hardcastle SJ, Chater A, et al. Autonomous and controlled motivational regulations for multiple health-related behaviors: between- and within-participants analyses. Health Psychol Behav Med. 2014 Jan 1;2(1):565-601.

- Azjen A. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav and Human Decision Processes. 1991 Dec 50(2):179-211.

- Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, et al. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav Res Methods. 2009 Nov;41(4):1149-60.

- Hayes A. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis, 2nd edn. New York: Guilford Press; 2018.

- Caneiro JP, O’Sullivan P, Smith A, et al. Implicit evaluations and physiological threat responses in people with persistent low back pain and fear of bending. Scand J Pain. 2017 Oct;17:355-366.

- Caneiro JP, O’Sullivan P, Lipp OV, et al. Evaluation of implicit associations between back posture and safety of bending and lifting in people without pain. Scand J Pain. 2018 Oct 25;18(4):719-728.

- Caneiro JP, O’Sullivan P, Smith A, et al. Physiotherapists implicitly evaluate bending and lifting with a round back as dangerous. Musculoskelet Sci Pract. 2019 Feb;39:107-114.

- Hovland C, Harvey O, Sherif M. Assimilation and contrast effects in reactions to communication and attitude change. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 55(2), 244–252.

- Deci E, Koestner R, Ryan R. A Meta-Analytic Review of Experiments Examining the Effects of Extrinsic Rewards on Intrinsic Motivation. Psychological Bulletin. 1999, Vol. 125, No. 6, 627-6.