Whether your goal is to increase muscle size, strength, or you’re training for general health and well-being, training the upper body is a must. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that individuals lift weights at least two times per week, working all of the major muscle groups, which of course include muscles of the upper body.

Enter the barbell bench press, which is not only a competitive lift in the sport of powerlifting, but is also a great way to train the chest, shoulders, and arms to get stronger, build muscle, and maintain good health.

In this article, we will describe how-to do the bench press, the muscles worked, the benefits, variations, and troubleshooting tips. Let’s jump right into it.

Equipment For The Bench Press

- Wrist wraps: Wrist wraps create a cast around the wrist to provide additional support. Many lifters find the compression of wrist wraps more comfortable for training and competition.

- Belt: Belts act to increase intraabdominal pressure and intramuscular pressure to increase stiffness of the trunk and allow for better force transfer from the lower body to the barbell and increase the ability of the lifter to move weight.

- Chalk: Chalk absorbs sweat from the hands and can result in a better grip on the barbell. Lifters may find that this helps their grip maintain the same distance through a lift.

- Length: 52″

- Width: 11″

- Height: 17.5″ Flat , 55.75″ at 85 degrees

- Steel: Frame – 3″x3″ 11 Gauge Steel

- Color: Brown

- Width: 4″

- Thickness: 10MM, Thickness Tolerance: +/- 1MM

None of the equipment listed above is essential but it can be helpful in moving more weight which can help with being more consistent in the gym.

How-To Bench Press

- Lay down on the bench with your head slightly in front of the barbell if viewed from the side. This helps ensure there’s enough room for the bar to move up and down without hitting the rack.

- Grab the bar with an overhand grip, using a grip width that’s about 1- to 2-hand widths’ outside your shoulders.

- Before lifting the bar out of the rack, fix your eyes on a point on the ceiling somewhere just in front (towards your feet) of the bar and pull your shoulder blades back into the bench.

- Lift the bar out of the rack and let it settle just over the shoulder joint.

- Take a big breath and hold it.

- Bring the bar down to touch your sternum, approximately 2 to 3” forward of where the bar started over the shoulder joint. In this position, the elbows and humerus should be angled at ~ 30 to 45 degrees relative to the torso.

- Press the barbell up and back so that it ends up directly over the shoulder joint.

To perform the barbell bench press, you’ll need a flat bench, a bar, and either a stand-alone bench press “rack” or adjustable squat rack to bench within.

Each person will set up a little differently but this is a good starting set up to help you find a repeatable and efficient technique. From here you can make small changes over time that are more comfortable or where you feel stronger. If you’re a visual learner, check out this video for in-depth bench press instructions.

Regarding the points of performance for the bench press for non-powerlifters, it is reasonable to mandate that the lifter’s butt and shoulders stay in contact with the bench for the duration of the rep and that the bar is not bounced off the chest. Competitive powerlifters will have additional rules to follow to train for a competition, e.g. pausing the bar motionless on the chest momentarily and -depending on the federation- keeping the head in contact with the bench and feet flat on the floor.

1. Positioning On the Bench

Where you lie down on the bench is important, as you want to be able to unrack the barbell from the j-hooks safely, but not hit them with the barbell during each repetition. We recommend lining up your eyes either directly under the barbell or slightly in front of the barbell (away from the rack). We recommend fixing your eyes on a point on the ceiling somewhere just in front of the barbell.

When viewed from the side, the lifter’s head will be under the barbell and the shoulder joint will be slightly in front of the bar in the j-hooks, e.g. further down the bench, away from the rack.

2. Grip and Touch Point

The grip width used and where the barbell touches on the chest at the bottom of the rep are tightly linked. The wider the grip, the more the elbows will be “flared” out to the sides, and the higher on the chest the bar will touch. Similarly, the closer the grip is, the lower the bar will touch on the chest, and the more the elbows will be “tucked” into the sides. With that in mind, grip width and subsequent touch point are mostly personal preference based on an individual’s tolerance and performance. .

A standard power bar has two landmarks that are useful for hand placement; the start of the knurling and the score marks. The start of the knurling measures 16-inches (40.64-centimeters) from side to side. Placing the index finger right at the start of the knurling is generally considered a “close-grip” bench, as it utilizes a shoulder-width grip. The score marks measure 31-inches (78.74-centimeters) from side to side. Placing the index finger on the score marks is the maximum grip width allowed in powerlifting and is considered a “wide-grip” bench.

To check for the correct grip width and touch point, make sure that the forearms are vertical at the bottom of the rep when the bar is touching your chest, e.g. not angled backward towards the head or forward towards the feet. If the forearms are angled backwards, the touch point is likely too high for the selected grip width. If the forearms are angled forwards towards the feet, the touch point is likely too low.

Additionally, check to make sure the forearms are also vertical when viewed from the front, not angled inwards or outwards. If the forearms are angled inwards, the amount of “elbow tuck”, which is shoulder adduction, is likely too great and the lifter should flare their elbows more. If the forearms are angled outwards, the lifter needs to tuck their elbows more.

Regardless of grip width and the extremes of different touch points, the barbell will be a few inches in front of the shoulder joint at the bottom of the rep when viewed from the side. For maximum efficiency, the bar will need to be pressed up and back quickly to a position directly over the shoulder joint. This produces a bar path that moves more or less diagonally from the touch point until it is over the shoulder and then more vertically until lockout.

We recommend taking an overhand grip with your pinky fingers on the score marks to start, as this medium-width grip is a good starting point. The touch point on the chest should be approximately mid-sternum, though it can vary significantly between individuals. The correct bar path will be down and forward during the descent, then up and back on the ascent.

3. The Bench Press Arch

After positioning yourself on the bench and taking the proper grip, we can move the upper body and trunk into an efficient position to bench press. This position will include some amount of scapular retraction and depression, along with extension of both the thoracic and lumbar spine segments. Combining these three movements together creates a stable base of support for the upper body to press weights and secures the body’s position on the bench itself. Collectively, these movements help form an “arch”, as the extended lumbar and thoracic spine create this shape during the bench press.

We recommend pulling your shoulders back and down into the bench, pushing your chest up, and placing your feet on the ground as close to your head as you can comfortably tolerate to create a stable and efficient arch.

It is possible to bench successfully without much of an arch, as some individuals do not have the flexibility to get into this position comfortably. Others don’t tolerate this amount of spinal extension even if it isn’t loaded directly. For these individuals, it may be useful to place plates or small boxes on the floor where the feet would otherwise go. This reduces the amount of lumbar extension the individual needs to adopt in order to bench press.

4. Unracking the Barbell

Taking the bar out of the rack, especially at heavy weights, can be the most difficult part of the lift. At this point, the bar is behind your shoulder joint and is at a relative mechanical disadvantage. This is especially true if we want to maintain the shoulder blade position we adopted earlier while we lift the bar up and over the edge of the j-hook. We’ll cover two different ways to solve this problem: 1) performing a self lift off, and 2) using a spotter.

For a self lift off, lie down on the bench, take the appropriate grip, and set the shoulders and upper back as described above. With your hips off of the bench, being pushed up towards the ceiling, and ensuring your arms are straight, lift the bar off the j-hooks and move it forward until the bar comes to rest directly over your shoulder joint. You are now ready to start the rep.

When using a spotter, you will need to communicate with them on how you want the lift-off, how many reps you’re doing, and when to help. By convention, most individuals use a “one-two-three” countdown when receiving a lift off, where the spotter helps lift the weight up after the lifter says “three”. Spotters should be instructed to “take the bar” and help you back into the rack if the bar starts going back down during the upwards phase of a repetition. Again, after taking the correct grip and position on the bench, count to three and, with the help of the spotter, lift the bar off the j-hooks and move it forward until the bar comes to rest directly over your shoulder joint. You are now ready to start the rep.

We recommend using a spotter to help you lift the bar off the rack, especially when the weights are challenging and always when you don’t have safety bars or rails. In a pinch, you can do a self lift off, but we strongly recommend only doing so with safeties. Most people in the gym are happy to be a spotter if you ask!

5. Bracing and Breathing

Breathing during the bench press is important for creating stability and stiffness in the body, thereby allowing the active muscles to transfer force efficiently. We will be discussing a Valsalva maneuver, which is when you take a deep breath in and hold it.

The suggestion that people should breathe in during the “downwards” phase and breathe out during the “upwards” phase, or similar recommendations to avoid the Valsalva maneuver to reduce risk of unwanted outcomes is not based in reality. Not only is this breathing pattern difficult, if not impossible to perform during challenging efforts, the risks of performing the Valsalva maneuver- which center around an increase in systolic blood pressure- remain unsubstantiated. Specifically, people reflexively hold their breath when lifting- effectively performing a mini Valsalva maneuver- to presumably increase intra-abdominal pressure.6

We recommend taking a big breath and holding it for the duration of each repetition. Before each rep, take a big breath in and hold it. After taking the breath, push your feet into the floor as if you are trying to push yourself off the head of the bench. This is going to create tension across the arch you created initially and that is a very strong structure. This is termed leg drive and we will discuss this more below.

Of note, you may see some individuals performing the bench press with a belt. A belt is useful for increasing the pressure (and subsequent stability) in the abdomen and chest for more efficient force transfer. Some people also report that it helps them feel “tighter” while performing the bench press. It’s mostly personal preference.

6. Touch and Go Bench vs. Pausing

When bringing the bar down to the chest, the goal should be to touch the barbell at approximately the same spot each rep. Depending on your grip width, this will change to be a lower (closer to your belly button) or higher (closer to your head) touch-point on your chest. A narrower grip is going to result in a lower touch point, whereas a wider grip produces a higher touch point.

The bench press can be performed with a pause on the chest or with a light touch, which is termed “touch and go”. The sport of powerlifting requires lifters to wait for the judge’s “press” command before they initiate the upwards phase of the bench press. Per the rules, the judges are looking for the bar to become motionless on the lifter’s chest prior to giving the command. Outside of this sports-specific consideration, it’s really up to the individual as to what style of bench they perform. Most people who are well-practiced with the paused bench press will end up lifting more weight paused, whereas those who primarily bench touch and go tend to bench more without a pause. Both have utility and if you are not competing in a sport that dictates one or the other, the decision is up to you.

We recommend aiming to touch the barbell in the middle- or lower-middle portion of their sternum when using a medium grip. We also recommend either a brief pause or light touch and go once the barbell touches the chest. For individuals who wear a sports bra in the gym, you may find that the band of the bra is a good reference point for you.

7. Leg Drive

Leg drive during the bench press refers to muscular force being applied from the lower body to the trunk and upper body during the rep. When done correctly, leg drive can improve force transfer from the muscles of the upper body into the barbell, thereby allowing the individual to lift more weight.

To use leg drive correctly, firmly plant the feet on the floor and push hard into the ground in an attempt to push yourself backwards (towards the rack) during the repetition. The engagement of the leg drive should be continuous during the lift but it should peak just before or as the bar is coming off your chest. This provides extra power to move the bar off your chest and create momentum through the lift. Be sure not to thrust the hips up during the repetition, as this isn’t really leg drive, and it will cause the butt to come off the bench pad.

8. Re-racking

At the top of the rep, the shoulders will still be pulled back into the bench, but the elbow will be fully extended. This marks the completion of the repetition and the bar is now in a position to rerack.

We recommend keeping the elbows extended and pushing the bar backwards into the uprights and j-hooks securely. This is another time where a spotter can help guide the barbell.

Common Bench Press Problems and Solutions

To assist you as you start on your bench press journey, there are a couple of common mistakes you can look for. Take time to set up a phone or small recording device in your gym to watch yourself if you are interested. Form is not correlated with injury, but the goal is to produce a repeatable and efficient movement pattern. If you see the following during a bench press you might want to take some time working to alter your form.

Bar path

As described above the j-shape or slanted bar path that gets the bar over your shoulder is incredibly important to reduce torque at the shoulder and make the lift easier. When you film yourself, if you are looking from the side and the bar comes straight up and then goes back you might be fighting torque a bit more than needed and making the lift harder.

The Solution: Think about driving the barbell back towards your shoulder as the bar leaves your chest and then drive up. The cue often given to lifters is “back” or “drive back.”

Butt is Coming Up

During powerlifting, your butt must stay on the bench during each attempt. In the gym however, this is not strictly necessary and is more of an arbitrary standard to hold a lifter to. The bigger problem is when people add weight to the bar and then start heaving their hips off of the bench during the rep. This represents a somewhat different exercise, making it difficult to compare to previous efforts where the butt was held in contact with the bench. We recommend sticking to the same standards for your bench press week to week.

The Solution: When you are practicing leg drive work on driving your feet along the floor instead of driving them down into the floor. This is going to 1) help you keep your butt on the bench and 2) transfer more power into driving the bar up and back toward the rack. You are going to feel like you are sliding yourself off the top of the bench.

Bar Rolling

When you watch videos of your bench press, if you see the bar rolling in your hand or the logos on the plates rotating around the bar, it means the bar is rotating and/or shifting during the rep. This isn’t necessarily wrong, but it is not very efficient.

The Solution: When you grip the bar tighter it is automatically going to roll the bar down your hand to the proximal part of your palm. At this point the bar is sitting more over the loading bone of the forearm and the force transfer between your arm and the bar will be more efficient. Through the whole duration of the movement think, ‘grip tight.’

Shoulders Rounding (Protraction)

If you are watching the lift and you can see your shoulders coming off the bench or moving to finish the range of motion, you are likely protracting your shoulder blades (scapulae) during the lift. This both reduces the stability of the upper body and increases the range of motion that you need to move the bar through. It’s not necessarily wrong or deleterious, but it likely less efficient than keeping the shoulders in place.

The Solution: When you set up, pinch your shoulder blades together as if you are trying to use them to grab the material of the bench. This creates a really stable surface to bench from and improves your arch. When you lift-off we don’t want you to undo this hard work you have done to create this shelf so the goal is going to be that you are continuing to pinch your shoulder blades together through the duration of the lift. A good cue to think of is “shelf” because you are creating a shelf with your shoulder blades that you will lie on during the lift.

Bar is Bouncing

If you watch your lift and see that you are pausing on your chest but the barbell is bouncing a lot or is sinking into your chest. you might be using extra energy to hold the bar steady or extra energy to move the bar through the additional range of motion. While “sinking” is a technique used in powerlifting, it is probably not the most efficient way to bench press for those just starting out.

The Solution: When you bring the bar down to your chest, imagine there is a piece of glass there that you can’t break, so you will bring the bar down to your chest and hold it on top of the glass but if you let it sink into your chest too much or bounce around the glass will break. Use your leg drive to bring your chest up to meet the barbell. You will be able to hold the bar steadier and not break the glass.

If you have a spotter, you can also ask them to remind you of cues you are working on as you are getting started in the lift. Remember, these tips are to help you lift more efficiently, they are not required. Benching in a way that is comfortable for you and your anthropometry is important. For individuals who want to improve your bench, start here.

What Are The Muscles Worked During the Bench Press?

During the bench press many muscles are loaded, however the following three are the ones contribute the most to the movement:

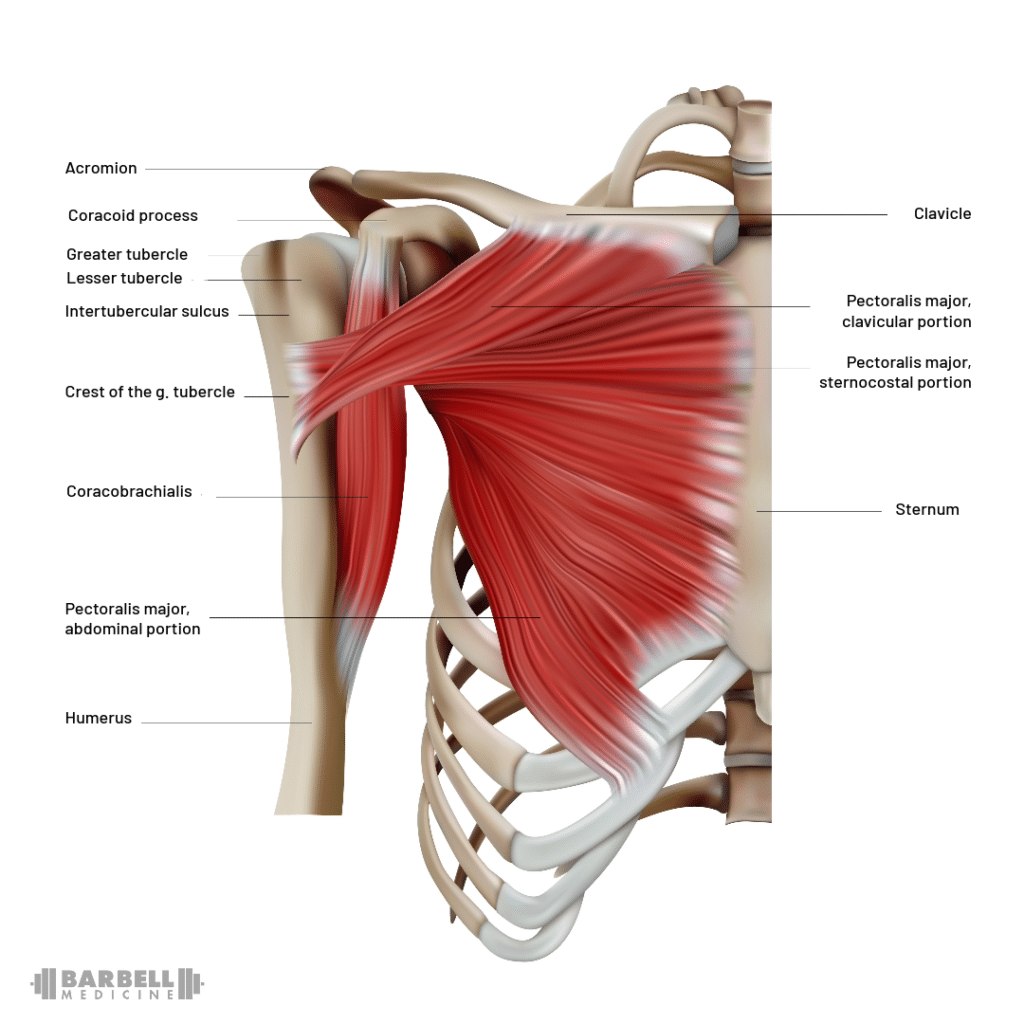

- The pectoralis major is the biggest muscle of the chest. In men, it is situated underneath the skin and subcutaneous fat. In women, it is located below breast tissue. There are two heads to the pectoralis major; the clavicular head that arises from the clavicle and the larger sternocostal head, which arises from the sternum, the upper costal cartilages of the ribs, and the sheet-like tendon of the external oblique muscle. The role of the pectoralis major is to flex the arm at the shoulder and internally rotate the humerus

- The anterior deltoid is one of three functional heads of the large, triangular muscle overlying the shoulder joint. The anterior deltoid is positioned on the front of the body, originating from the lateral one-third of the clavicle. The anterior deltoid assists in abducting the arm at the shoulder as well as shoulder stabilization. For completeness, the middle or acromial head is the largest of the three and originates from the acromiom’s lateral margin, and the posterior head originates from the scapular spine. All three heads attach to the deltoid tuberosity of the humerus.

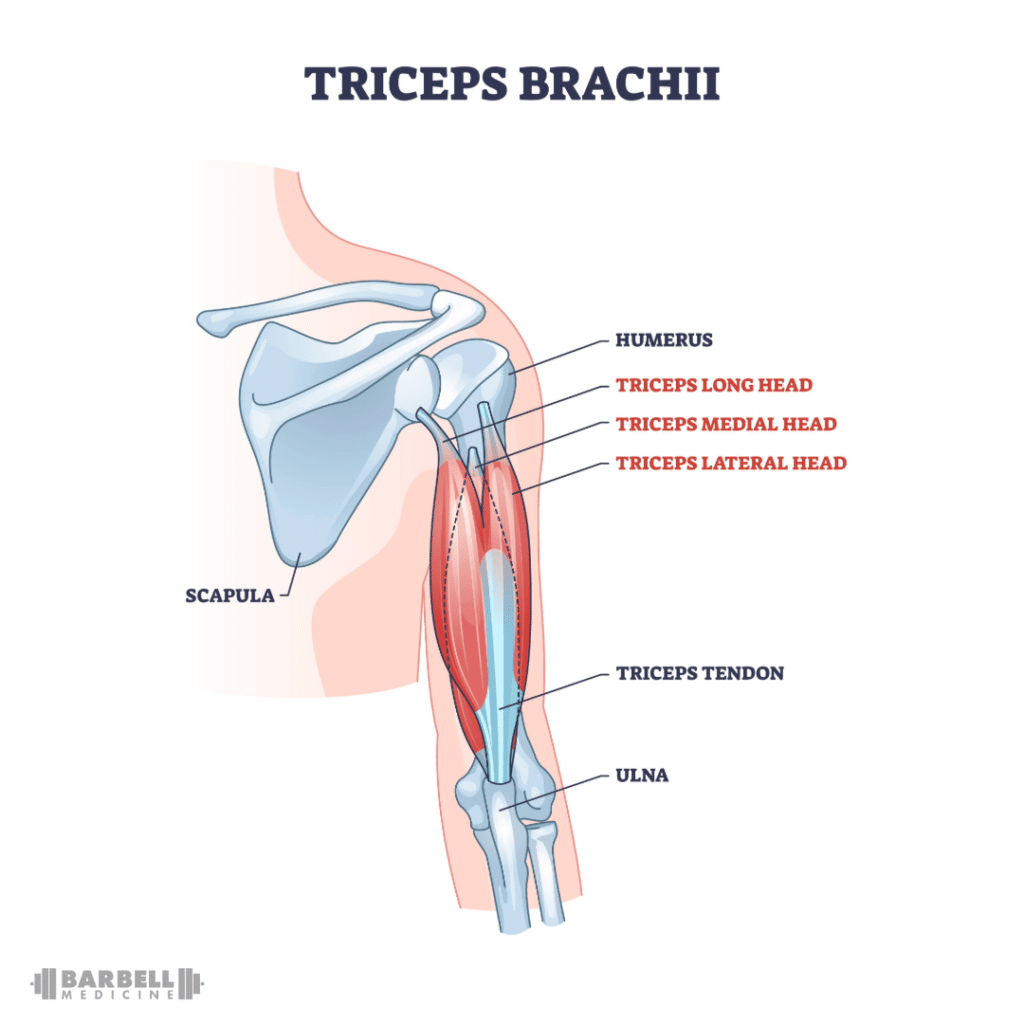

- The triceps brachii are also made up of three parts, e.g. the long, lateral, and medial heads. The triceps are the only muscles that lie parallel to the posterior humerus. Their primary duties include extending the elbow and stabilizing the shoulder joint.

To further explain how each muscle is working during the movement, we will break up the bench press into two separate phases based on the type of muscular contraction, e.g. the eccentric and concentric phases.

An eccentric contraction is one where the muscle produces force while increasing in length. In the bench press, this occurs when the barbell is lowered from the starting position down towards the chest. During the eccentric phase of the lift the pectoralis major, the triceps brachii, and the anterior deltoid are lengthening to bring the bar down toward the chest. These muscles are exerting a force against the bar to slow its acceleration due to gravity.

In contrast, a concentric contraction is when the muscle is actively shortening while exerting force against an external object or force. In the bench press, the concentric phase starts when the bar leaves the chest and is pressed back upwards to the starting position. On the way up the pectoralis major, triceps brachii, and the anterior deltoid are contracting concentrically to move the weight against the force of gravity.

Together, these three muscles create force via muscular contraction in a coordinated fashion to raise and lower the bar under control. The barbell bench press requires lots of muscular force production from these muscles and others, thereby generating improvements in strength and size when programmed correctly. However, there are multiple variations of the barbell bench press that also do this, albeit in slightly different ways.

Bench Press Variations

For example, the angle of the bench press gets a lot of attention when it comes to discussing both muscle growth and strength development. A number of studies have investigated the electrical activity, e.g., “excitation” of the anterior deltoid, pec major (and parts thereof), and other muscles during flat, incline, and decline bench press, with mixed results.

One study found no significant differences in excitation levels of the pectoralis major, anterior and posterior deltoid, or latissimus dorsi muscles during 6-repetition maximum efforts on flat, incline, and decline bench presses.1 A similar study found no statistically significant differences in pectoralis major, anterior deltoid, or lateral deltoid excitation when comparing a flat bench press to a decline or incline bench press, regardless of whether dumbbells or barbells were used.2 While other studies have found EMG differences (a measure of muscle excitation) using different bench angles, these differences are not really predictive of actual outcomes, e.g., differences in muscle size and strength when using one or more variation(s) over the other.3

When it comes to outcomes we care about, like chest muscle hypertrophy or strength, the scientific evidence isn’t much better. For example, another study found that there were no meaningful differences in pec major hypertrophy or pressing strength after 8 weeks of doing only flat bench, only incline bench, or both flat and incline bench presses.4 Finally, a study comparing 4 weeks of doing either push-ups or bench presses three times a week showed similar improvements in both 1-Repetition Maximum (1RM) bench press strength and chest hypertrophy.5

Taken together, it seems like most pressing exercises will produce similar hypertrophy outcomes with respect to the pectoralis major, anterior deltoid, and triceps. For this purpose, we’d recommend using a variety of different pressing exercises using relatively long ranges of motion in order to maximize response. Check out our article for a sample push day workout and the list below of our favorite pressing exercises for hypertrophy:

- Flat Barbell Bench Press

- Incline Dumbbell Bench Press

- Seated Overhead Press

- Dumbbell Flye

- 1-arm cable lateral raises

For strength, we’d predict that an exercise that’s more similar to how strength is being tested will produce a greater improvement in the long-term. In other words, if you want to bench press more weight, you’ll want to train the bench press and similar variations to get better at its specific movement pattern. A few of our favorite bench press variations for strength include:

- 2-Count Paused Barbell Bench Press

- Pin Bench Press at Chest-Level

- 2-Board Bench Press

- Floor Press

- Close Grip Bench Press

Improving bench press performance also requires using good form, which is defined as a repeatable and efficient technique that meets any predetermined points of performance of the movement.

What Are The Benefits of Bench Press?

From a health perspective, resistance training supports a healthy lifestyle through improvements in function and physiology. As a resistance training exercise, the bench press is a great way to train the upper body, though it also uses the muscles of the lower body to stabilize the trunk and transfer force to the barbell. Let’s discuss a few of the benefits associated with resistance training and the bench press.

Improved Strength

Muscular strength is the amount of force produced by the muscles that is measured during a given task or test. Changes in strength are not due to a single adaptation. Instead, strength improvements are the result of a number of fitness adaptations across multiple domains including the central nervous system, peripheral nervous system, skeletal muscle, tendon, and bone, among others.

Participation in strength training is both important for health. For example, a large review found that those who resistance train 2-3 times per week have a 23% reduction in all-cause mortality.7 There also appears to be a dose-dependent effect of resistance training on health, where greater lifting volume tends to improve health more than lower volumes.8

Resistance training readily improves strength, though there is a significant variation in how people respond to resistance training. 9,10,11 For example, a recent review of 40 resistance-training studies where strength was repeatedly measured throughout the study period – not just before and after – found that it took an average of 4.3 weeks before a demonstrable increase was recorded. The time point when the first increase in strength became apparent varied between 1 and 12 weeks. The magnitude of strength increase also varied across the 40 studies, ranging from ~3 to 40% for studies looking at squat 1-repetition max strength.12

Overall, engaging in resistance training is important for both health and performance. In addition to regular participation, using progressive overload to match the training to an individual’s current fitness level and needs is the key to success.

Increased Muscle Size

Muscle hypertrophy is defined as an increase in total mass of a muscle, which occurs when muscle protein synthesis exceeds muscle protein breakdown for sustained periods of time. Muscle fibers change in size in response to the demands placed upon them by way of altering protein synthesis and breakdown signals. In the conventional hypertrophy model, lifting weights requires the muscles to produce force in a manner that ultimately stimulates muscle protein synthesis.

Though the mechanisms for generating increased muscle mass are the same across individuals, hypertrophy responses vary across individuals using the same program. For example, a classic study showed that muscle size changes ranged from -11% to +30% in 287 adults following the same program over 6-months. The age and sex of the individual didn’t really influence their hypertrophy response, but each individual had a unique response to the program.11

Nonetheless, the variables that drive muscle hypertrophy require mechanical tension. Lifting weights forces the muscle to overcome external resistance, thereby creating mechanical tension. Because the bench press loads a lot of muscle mass across a relatively long range of motion (ROM), it can be useful for increasing muscle size in the chest, shoulders, and arms.

Injury Risk Reduction

Performing resistance training that improves strength and muscle size seems to reduce the risk of injuries.12 In addition, resistance training can strengthen bones and promote bone growth, which is crucial for individuals who are at risk of osteoporosis, such as menopausal women. 13

Reduced Risk of Cardiac Disease

Heart disease is the leading cause of death globally, taking an estimated 17.9 million lives each year, about ⅓ of which happen in those under 70. While death rates from CVD, CHD, and stroke have declined in the United States since 1975, it’s still the leading cause of death and exercise – including resistance training- has been shown to reduce the risk of heart disease.14

For example, resistance training has been shown to reduce low density lipoprotein (LDL) and triglycerides modestly, while increasing high density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol. Lifting weights also reduces resting blood pressure. A recent meta analysis of 391 studies- half investigating the effect of blood pressure medications and the other half looking at the effects of exercise- found that in those with resting blood pressure greater than 140mmHg:

- Endurance exercise lowered systolic blood pressure by 8.69 mmHg

- Resistance training lowered systolic blood pressure by 7.83 mmHg

- Combined endurance and RT lowered systolic blood pressure by 13.5 mmHg15

Of note, it’s been suggested that resistance training causes pathological changes in the left ventricle, causing it to grow thicker. This is called left ventricular hypertrophy, or LVH, which is defined as an increase in the mass of the left ventricle. Normally, LVH is secondary to an increase in wall thickness, an increase in cavity size, or both, but presentations vary depending upon the underlying pathology.

For resistance training, the thought is that because blood pressure goes up when lifting heavy, the heart would have abnormal changes from this kind of stress and lead to heart disease down the road.

It was proposed that endurance training caused an increase in both the size of the left ventricle’s chamber and also its wall thickness, in order to deal with an increased amount of blood being pumped into and out of the heart. Because most of these adaptations were thought to be driven by processes that occurred during the relaxation phase of the heart- when the muscle fibers of the heart lengthen to accommodate being filled with blood, this was dubbed “eccentric hypertrophy”.

In contrast, it was suggested the resistance training caused predominantly an increase in the thickness of the muscle in the left ventricle without a concomitant increase in the size of the chamber. Because this was thought to occur while the heart was actively contracting, e.g. shortening, against a high pressure circuit, it was dubbed “concentric” hypertrophy.

While eccentric hypertrophy does occur in endurance training, this is the same adaptation seen in resistance training. What’s more, the thickening of the ventricle that occurs from endurance training is far greater than what’s seen in resistance training, with the chamber size increasing in a proportional manner. The ratio between ventricular wall thickness to chamber size ratio is not meaningfully different between endurance and resistance training either. 16, 17,18

Overall, resistance training has converging lines of evidence showing that it reduces the risk factors associated with heart disease, reduces all cause mortality, and does not negatively affect heart function. In keeping with the current physical activity guidelines, we think that everyone who is able to lift weights should do so.

Better Metabolic Function

Resistance training reduces average blood sugar levels in those where it’s high, e.g. those with type 2 diabetes or insulin resistance. For example, there’s a 17% reduction in risk of developing diabetes in those who lift compared to those who don’t. 19 Recent data also shows that lifting weights improves blood sugar management in those with diabetes, particularly if the individual actually gets stronger when lifting weights. Those with type 2 diabetes who had greater improvements in their 1RM strength tended to see better improvements in their average blood sugar levels, for example. 20

Summary

The bench press is a great way to build muscle in your upper body, particularly the chest, shoulders and triceps. As you are getting started, don’t worry about being perfect. The bench press has some technical details and personal preferences to work out. Don’t be afraid to try different grip widths, touch points, or equipment as you find what works best for you. There isn’t one perfect bench press or style. Find what works for you and is repeatable week after week. For even more information on the bench press check out the Barbell Medicine YouTube video on the bench press: The Bench Press Prescription.

If you’re interested in building strength or muscle with the bench press, but don’t want to go through the trouble of planning out your program, we may have just the thing for you. At Barbell Medicine, we’ve got a team of licensed professionals who can craft both your training program and diet plan to help you reach your personal fitness goals.

Take a look at our catalog of evidence-based training templates that our team has carefully crafted to help our clients reach various fitness goals, and if you can’t find what you want there, reach out to us for a personalized training program that we will put together just for you.

References

- Saeterbakken, Atle Hole et al. “The Effects of Bench Press Variations in Competitive Athletes on Muscle Activity and Performance.” Journal of human kinetics vol. 57 61-71. 22 Jun. 2017, doi:10.1515/hukin-2017-0047

- Christian, Jamison R et al. “Analysis of the Activation of Upper-Extremity Muscles During Various Chest Press Modalities.” Journal of strength and conditioning research vol. 37,2 (2023): 265-269. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000004250

- Vigotsky, Andrew D et al. “Greater electromyographic responses do not imply greater motor unit recruitment and ‘hypertrophic potential’ cannot be inferred.” Journal of strength and conditioning research vol. 31,1 (2017): e1-e4. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000001249

- Chaves, Suene F N et al. “Effects of Horizontal and Incline Bench Press on Neuromuscular Adaptations in Untrained Young Men.” International journal of exercise science vol. 13,6 859-872. 1 Aug. 2020

- Kotarsky, Christopher J et al. “Effect of Progressive Calisthenic Push-up Training on Muscle Strength and Thickness.” Journal of strength and conditioning research vol. 32,3 (2018): 651-659. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000002345

- Hemborg, B et al. “Intra-abdominal pressure and trunk muscle activity during lifting. IV. The causal factors of the intra-abdominal pressure rise.” Scandinavian journal of rehabilitation medicine vol. 17,1 (1985): 25-38.

- Dankel, Scott J et al. “Dose-dependent association between muscle-strengthening activities and all-cause mortality: Prospective cohort study among a national sample of adults in the USA.” Archives of cardiovascular diseases vol. 109,11 (2016): 626-633. doi:10.1016/j.acvd.2016.04.005

- Figueiredo, Vandré Casagrande et al. “Volume for Muscle Hypertrophy and Health Outcomes: The Most Effective Variable in Resistance Training.” Sports medicine (Auckland, N.Z.) vol. 48,3 (2018): 499-505. doi:10.1007/s40279-017-0793-0

- Borde, Ron et al. “Dose-Response Relationships of Resistance Training in Healthy Old Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Sports medicine (Auckland, N.Z.) vol. 45,12 (2015): 1693-720. doi:10.1007/s40279-015-0385-9

- Lesinski, Melanie et al. “Effects and dose-response relationships of resistance training on physical performance in youth athletes: a systematic review and meta-analysis.” British journal of sports medicine vol. 50,13 (2016): 781-95. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2015-095497

- Ahtiainen, Juha P et al. “Heterogeneity in resistance training-induced muscle strength and mass responses in men and women of different ages.” Age (Dordrecht, Netherlands) vol. 38,1 (2016): 10. doi:10.1007/s11357-015-9870-1

- Lauersen, Jeppe Bo et al. “The effectiveness of exercise interventions to prevent sports injuries: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials.” British journal of sports medicine vol. 48,11 (2014): 871-7. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2013-092538

- O’Bryan, Steven J et al. “Progressive Resistance Training for Concomitant Increases in Muscle Strength and Bone Mineral Density in Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Sports medicine (Auckland, N.Z.) vol. 52,8 (2022): 1939-1960. doi:10.1007/s40279-022-01675-2

- Paluch, Amanda E et al. “Resistance Exercise Training in Individuals With and Without Cardiovascular Disease: 2023 Update: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association.” Circulation vol. 149,3 (2024): e217-e231. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000001189

- Naci H, Salcher-Konrad M, Dias S, et al How does exercise treatment compare with antihypertensive medications? A network meta-analysis of 391 randomised controlled trials assessing exercise and medication effects on systolic blood pressure British Journal of Sports Medicine 2019;53:859-869.

- Williams, Mark A et al. “Resistance exercise in individuals with and without cardiovascular disease: 2007 update: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Council on Clinical Cardiology and Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism.” Circulation vol. 116,5 (2007): 572-84. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.185214

- Spence, Angela L et al. “A prospective randomized longitudinal MRI study of left ventricular adaptation to endurance and resistance exercise training in humans.” The Journal of physiology vol. 589,Pt 22 (2011): 5443-52. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2011.217125

- Naylor, Louise H et al. “The athlete’s heart: a contemporary appraisal of the ‘Morganroth hypothesis’.” Sports medicine (Auckland, N.Z.) vol. 38,1 (2008): 69-90. doi:10.2165/00007256-200838010-00006

- Momma H, Kawakami R, Honda T, et alMuscle-strengthening activities are associated with lower risk and mortality in major non-communicable diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies British Journal of Sports Medicine 2022;56:755-763.

- Jansson, Anna K et al. “Effect of resistance training on HbA1c in adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus and the moderating effect of changes in muscular strength: a systematic review and meta-analysis.” BMJ open diabetes research & care vol. 10,2 (2022): e002595. doi:10.1136/bmjdrc-2021-002595