As a physical therapist, I have found that the meniscus is often blamed for people experiencing knee pain. Many people are aware that a meniscus can be damaged or “torn”; this raises questions about whether it is the cause for knee pain, and what should be done about it. In this article, I will discuss what these findings mean and make the case that we can often improve knee pain without doing anything specific to the meniscus. I will also provide practical suggestions for training modifications to help manage knee pain, and get back to participating in the activities you enjoy.

What is a meniscus?

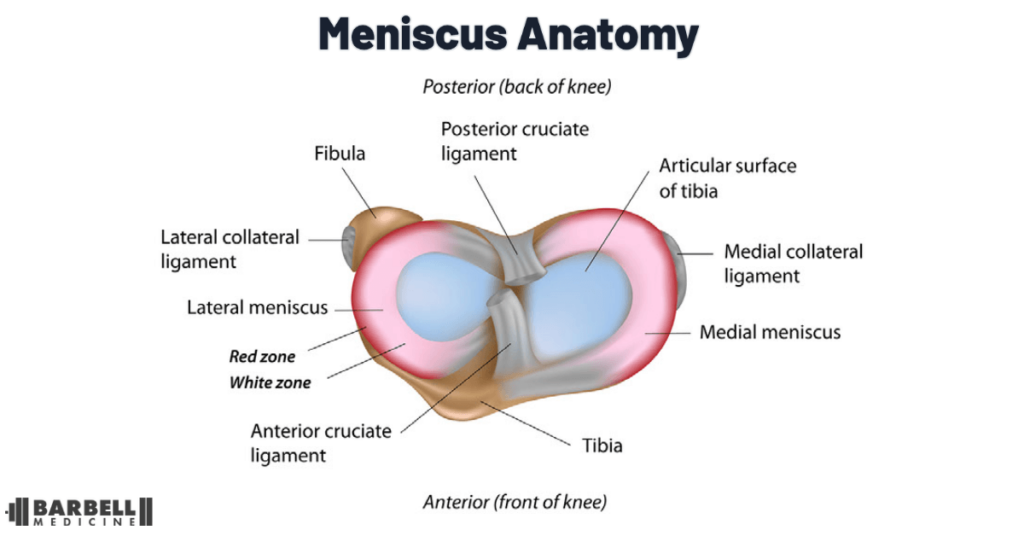

The meniscus is a crescent-shaped fibrocartilaginous structure, which is made of densely braided collagen bundles. Knees have two menisci that sit atop the tibia as part of the knee joint, one on the inner (medial) aspect, and one on the outer (lateral) aspect. The medial meniscus is more “C-shaped”, whereas the lateral meniscus is more circular. They are concave in shape and help the femur join the tibia. They help in distributing load throughout the joint, especially as the knee extends during activities like walking.

Meniscus changes are common as the result of sport, or aging. One study found that among individuals with no knee symptoms, average age 44 years, 30% had a meniscus tear. Another study of collegiate basketball players with no symptoms found that 50% of athletes had meniscus changes in the preseason, increasing to 62% in the postseason. Again, these athletes did not have any knee symptoms. The point is that “degeneration”, “tears”, and overall changes can be normal and should not be automatically assumed to be the singular cause of someone’s knee symptoms. In a systematic review of almost 300 athletes with no symptoms, about one-third had abnormalities in their meniscus.

There does not appear to be a specific place on the knee where athletes can feel their meniscus. One of the most discussed studies involved an orthopedic surgeon letting another surgeon perform an arthroscopic procedure on his knee without anesthesia. This is a study on just one person, of their two knees — but allowing for direct pressure on the meniscus during surgery without any anesthetic produced mild symptoms.

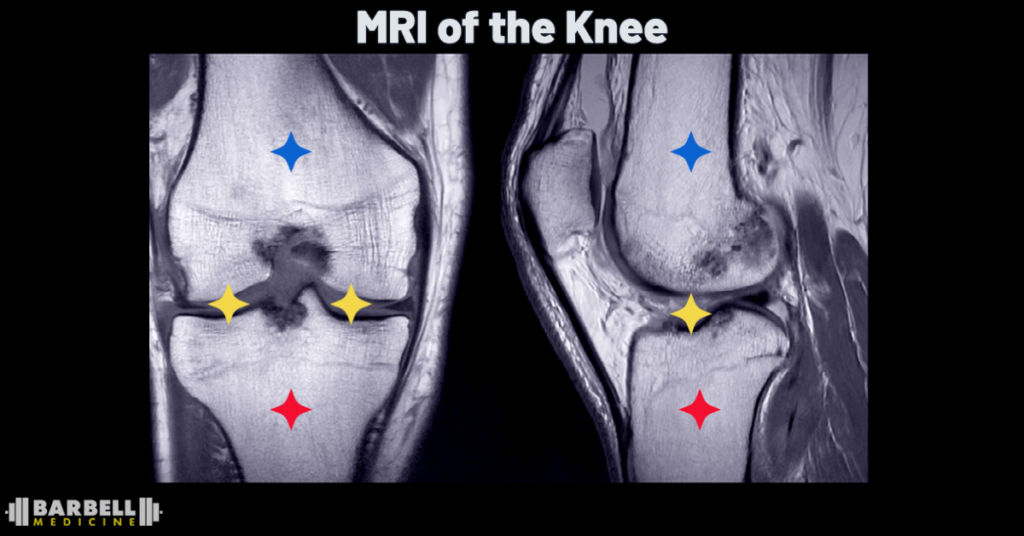

In many cases, the changes observed on imaging tests like MRIs can be interpreted as part of the natural aging process. We accept that aging causes skin wrinkles, and graying of our hair — but we also experience changes in other locations. It does not mean that joints are “worn out”, or that these changes are dangerous. If athletes live in fear of “wearing out” their joints, the real question is: what are they saving their joints for? If we’re not able to do the things we want, shouldn’t we focus on ways to allow us to do those things, instead of avoiding them altogether?

A typical course of action when a joint hurts is to seek imaging. The issue being if these changes are present, it can lead to overly aggressive steps in management. If a lifter develops knee pain, and immediately seeks imaging, the likelihood of finding some change is high, but that does not mean that change was not present prior to symptoms. Rushing for an intervention not only takes away from giving symptoms time to calm down, but can lead to a course that further limits an athlete’s ability to be active and train.

Do meniscus injuries cause knee pain?

Pain is complex. There is seldom just one “thing” that causes pain and symptoms. Recent changes to a training program, such as just starting a season in sport, sudden increases in volume or intensity, or beginning a new exercise modality like running or lifting, or having impaired sleep and recovery, can all contribute to experiencing symptoms. It does not mean there is anything pathological in the joint, or that these pain symptoms require a specific intervention on the joint. Current evidence, across multiple studies, advocates for conservative treatment as the first-line of treatment for knee pain associated with meniscal changes.

When should someone seek medical evaluation for knee pain?

There are specific instances where further evaluation is warranted. If you experienced a sudden mechanism of injury such as a slip, fall, or sudden twisting movement followed by increased swelling or inability to bear weight, you should seek evaluation from a healthcare provider. Swelling typically occurs along the inside joint line of the knee. If it is difficult to see the border of your kneecap, or swelling appears as though there is an orange along the inside of your knee — that would be sufficient for evaluation. If you are experiencing prolonged decreased range of motion or “locking” of your knee, such that it feels “stuck” in one position, that also warrants evaluation. If these symptoms are transient and resolve on their own, or if none of these are present, more conservative management is likely to be a reasonable strategy moving forward.

What does conservative management mean?

Simple modifications to what a person is doing can help reduce symptoms over time, while increasing their tolerance to the desired activities. Complete rest is almost never recommended, and modifications can always be made to accommodate symptom fluctuations, as well as the person’s activity or athletic goals. A 40 year old who is just starting their journey to becoming active, versus a 21 year old elite athlete in-season for their sport, will have drastically different starting points, but both can remain active.

Most pain symptoms arise from simply doing too much, too soon. Activity can be managed by finding an appropriate starting point, and beginning to build capacity from there. Progression is rarely linear and it is common for symptoms to wax and wane as a person progresses. There is no “one size fits all” approach, but we will provide suggestions for people who are just starting to train, as well as those who have been training consistently for years and are dealing with a recent setback.

What to do if you just started exercising and have knee pain?

The first step is to reflect on your recent activity patterns. Did you recently start walking more? Did you start back in the gym? Did you spend last weekend laying 1000 square feet of flooring, after not being on your knees for years? If any of these scenarios sound familiar, there is hope: it is likely that you simply overdid it, and will get better with some simple modifications, rather than requiring medical scans or surgery. It can be helpful to quantify your recent activity to look for big jumps. For example, if you have not performed squats in five years and recently started back three times a week, it is likely not the squats themselves, as much as how much and how hard you have been doing them since returning to training. If you have not been kneeling in the past decade and spent an entire weekend doing so, it is more likely that the novelty and “dosage” of the activity is what is contributing to pain more than any structural change in your knee joint.

In these kinds of situations, typical resolution of symptoms with appropriate modifications will take two to four weeks. That does not mean absolute rest; it is important to stay active within what you can manage and tolerate. You can continue to train, but you may need to modify your exercise selection and/or training loads. It is fine to perform bodyweight exercises as a means of getting in some movement, or using machines as a way of finding new movements that you can tolerate. If symptoms have arisen after a house project and you have not been active recently, even short walks can get you moving and feeling better. It can be beneficial to start small and quantify your progress. A 10 minute walk that progresses to 15 minutes still may be short of the end goal, but it is a 50% improvement in activity that you can do with stable or improving symptoms.

If pain is severe enough that you are having difficulty bearing weight through your leg, and there was a clear mechanism of injury such as a fall or sudden twist, that would benefit from medical evaluation. If there was no mechanism of injury, you still may need to modify weight bearing for a short period of time. That does not mean completely unloading the leg, but rather adopting a “weight-bearing as tolerated” gait. Using crutches, you put as much weight as feels comfortable on the leg that hurts. The crutches help to support the symptomatic leg, not completely unload it. The goal being to progressively place more weight down over the next few days to where you can walk without issue again.

If you are experiencing swelling that is bothersome or limiting, elevating the leg by propping your heel up on a cushion so that the back of your knee is off the ground and your leg is above your heart can help both regain any range of motion that is lost, as well as reduce swelling. An over-the-counter compression sleeve can also be useful to help with swelling, especially if the demands of your job require you to be on your feet for extended periods and the swelling itself is limiting. However, if the swelling is not bothersome or limiting, it does not necessarily require any direct treatment or intervention. This period is about finding the entry point for what you can tolerate and listening to your symptoms. Again, absolute rest is not appropriate; and finding ways to move with minimal symptoms will facilitate progress.

How-to rehab knee pain from a meniscus injury

The appropriate amount of load is entirely dependent on the person. There is no specific set of exercises that will guarantee everyone’s return to their desired activity. There is also a wide range of movements that can help you return to being active. There are no “bad” exercises, but an athlete who started experiencing knee pain while squatting 500 pounds, one that is attempting to play basketball 4 times a week, and someone attempting to just meet physical activity guidelines will need unique approaches to help them reach their goals.

We advocate for the use of autoregulation when it comes to weight selection. Ratings of perceived exertion (RPE) can be an excellent way of selecting the intensity of an exercise but there is a subtle difference between training to increase absolute weight and training to feel better. The normal anchor for RPE 8 is “could” you do 2 more repetitions at the selected weight for performance, but when working to decrease symptoms it is more beneficial to anchor to whether you “should” do 2 more repetitions. The difference leaves a wider margin of error and does not require an athlete to base their selection from effort alone

A powerlifter (or even recreational lifter) using exercises like squats, deadlifts, or lunges in their program needs to be able to squat, deadlift, and lunge in order to train as they would like. None of these exercises are bad; however, if squats are currently problematic, modifications can be made to range of motion by performing pin squats in a tolerable range of motion. The decreased range of motion then gives an athlete two outcomes to track progress, the weight on the bar, and the range through which the exercise is performed. We would recommend working on one variable during each session. One squat session may be anchored to increasing weight through the range that was tolerable prior while the next decreasing the height of the pins to expose to a great range.

If that athlete cannot squat due to symptoms, they may try a leg press, hack squat, or using a different implement such as a goblet squat, lunge, or a leg extension machine. It is more about finding what is tolerable for that person, and as symptoms subside returning to their normal training program. If symptoms are present with a movement such as a lunge, it may be limiting the range of motion temporarily by keeping an athlete’s shin more vertical. As symptoms subside, the knee can start to move more out over the toes again. There is not one “right” way to move, and each of us has unique training needs and goals. The over simplified recommendations being a mix of:

- Modify load

- Modify range of motion

- Modify exercise selection (inclusive of loaded, bodyweight, bilateral, and unilateral movements)

- Manage expectations

The athlete who has recently started in a basketball league and is experiencing knee pain may need to scale their overall participation time. The same resistance training modifications listed above may apply, but if there has not been any recent exposure to landing and changing direction, the athlete would benefit from a scaled version of those exercises. We have an extended piece addressing means of incorporating power into a rehabilitation program that can be found here.

If knee symptoms occurred after starting a fitness journey, the starting point likely needs to be more conservative. The good news is there are countless ways of increasing activity and finding the option that works best for the person, and helps with symptoms. The focus does not need to be as much on specific sets and reps, or the weight moved as the moving is the more important part. A beginning set of exercises may look as simple as:

- Biking for 10 minutes

- Straight leg raises

- Sit to stands from a chair

- A single leg exercise of choice

Here, the person is getting some aerobic exercise, some basic resistance exercise, and some exposure to balance. It does not need to be complex. This may be enough to decrease symptoms and allow a person to return to doing their daily activities. From there, we would expect that biking times would increase or maybe another form of cardiovascular exercise would come into play to where the person would eventually get to the recommended 150 minutes of moderate level aerobic exercise. Sit-to-stands can be progressed to a loaded squat, machine based program, or a modality like kettlebells to where the person is resistance training 2x/week.

The sets and reps do not matter as much for the person beginning to increase activity, but we do need ways to scale progress and the movements do need to be sufficiently challenging. There are countless ways of tracking this progress from increasing weight for a movement, increasing the number of repetitions performed, increasing the range of motion through which an exercise is performed, or being able to perform the same number of repetitions at a lower RPE. For intensity, the goal should be for individuals to be at least a 5-6/10. Using the “could vs. should” principle above, symptoms may factor into this rating. A reasonable guideline while becoming more active could be to not increase symptoms more than 2 points out of 10 while performing the movement. If this is occurring consistently, modifications to range of motion, load, or exercises are likely needed.

Will lifting weights wear out the knees?

A common fear is that activities like resistance training or certain forms of aerobic conditioning will necessarily “damage” joints. This fails to account for how well humans can adapt. We expect outcomes like increased muscle mass with resistance training, or increased aerobic capacity with running, but other tissues are adaptable too. A 2020 study found that individuals who met physical activity guidelines, did not smoke, drank alcohol only in moderation, and had a BMI below 25 kg/m2 were able to stave off chronic disease by 10 years compared to peers who did not. That is it. It was not a special set of exercises, nor did it need constant supervision for “perfect technique”.

Across all joints, the research shows that athletes adapt, but athletes also possess a high degree of changes in their joints without any repercussions for either symptoms or performance. Joints may hurt from time to time, but symptoms often resolve on their own. Menisci adapt to loading, but this depends on the “dosage” of training frequency, intensity, direction, and type of exercise. Any of those variables may need to be modified for a person and their symptoms, so that training and daily activities can continue.

The meniscus’ primary function of “load distribution” assumes that some form of “load” is actually present. While no loading strategy has proven superior, we do know that prolonged absence of load is not good for overall musculoskeletal health. Undergoing a meniscectomy also changes loading patterns in the knee. The removal of tissue alters the distribution of forces; while the long term outcomes here are typically not different than more conservative forms of treatment, it could be argued that removing the meniscus is taking away some of the cushioning in the knee.

How-to exercise after meniscus surgery

If surgery is the preferred option for a given person, there will need to be modifications to training and activity to allow for proper healing. The surgery itself does not heal the need so much as provides an environment for the knee to heal itself. As above, prolonged unloading of the knee after surgery is not ideal. However, it is also not advised to immediately return to the same prior levels of activity after surgery. The two biggest issues to address after surgery are regaining full knee extension and controlling swelling. There may be weight-bearing limitations in the short term to allow for healing, but there are still activities that an athlete can do to attempt to maintain strength until higher loads can be applied. The advice here is the same as with the initial onset of symptoms in that elevating the knee to help with swelling, and propping up the heel to work on regaining extension are helpful. If you are looking for an extended plan for return to training after surgery, we have a specific piece on this topic here.

We hope this advice helps, but if you continue to experience symptoms, we are happy to provide a consultation with the pain and rehab team. Finding your specific entry point sometimes needs a collaborative effort and our team is happy to help provide you with a plan to increase activity and return you to doing the activities you love.