Anyone who has experienced severe low back pain or ‘sciatica’ has a story to tell, and it’s usually not a pleasant one. Being unable to sit up out of bed without breathtaking pain, struggling to put your socks on in the morning, losing the ability to do the things you love, and feeling like you’re trapped in your own body describe the usual daily experience.

Perhaps you or one of your friends or family members have experienced this before. Maybe you’ve seen a terrifying Instagram post, Google search result, or physical model in a doctor’s office displaying images of herniated discs or nerves being compressed. This condition is typically associated with pain, burning, numbness, or tingling down the back of the leg.

While these symptoms can be unsettling, there is hope for those who are struggling with this condition. In this article, we’re going to cover what sciatica is and provide actionable steps to continue exercise, increase tolerance for activity, and get back to the activities you enjoy in life. Let’s get started.

What is Sciatica?

Sciatica is a general term used to describe back pain that travels down the leg. Although the term is often used to describe nerve-related low back symptoms, the label doesn’t have an official definition, and people tend to mean different things when using the term. Let’s look at some examples:

________

Dan is a 40 year old police officer who has been dealing with low back pain, occasional numbness and muscle weakness in his right calf, and a burning/tingling sensation down the back of both thighs for the past two years. His Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) showed ‘Degenerative Disc Degeneration (DDD) at L4/L5 and L5/S1 and foraminal stenosis at L5, severe on the right and moderate on the left’. This was suspected to be causing his moderate right side radiculopathy, mild left radicular pain, and low back pain. Whenever he has a flare-up, he often says “My sciatica is flaring up again.”

___

Amber is a 27 year old nurse who had a ‘sciatica flare up’ when helping to transfer a patient from a wheelchair to their bed. She noted extreme lower back pain with ‘sharp, shooting pains’ that radiated into both of her glutes. For the past three days she has had severe pain any time she would reach over to pick something off of the floor and has been generally hesitant to move.

_________

Both of these people labeled themselves as having sciatica, but note the differences in what they are experiencing. Dan is experiencing numbness and muscle weakness in his right calf. These symptoms indicate a loss of nerve function, which would be called radiculopathy. [1]

Radiculopathy

Radiculopathy comes from the Latin radix, meaning “root,” and the Greek pathos, which means “suffering or emotion.” The diagnosis of radiculopathy indicates that a nerve root exiting from the spinal cord is compressed or irritated, leading to a loss of normal function. This can cause a reduced or absent reflex response, a loss of sensation, and/or a loss of muscle strength.

In Amber’s case, she wasn’t experiencing any numbness or a loss of strength, but rather a ‘sharp, shooting pain’ from her lower back down into her glutes. This nerve-related pain, also associated with irritation of a nerve root in the spine, would be classified as radicular pain [1]. Although the pain was ‘sharp’ in Amber’s case, other common pain descriptors would include a dull or burning ache, “pins and needles”, or tingling for example.

Both lumbar radiculopathy and lumbar radicular pain can exist exclusively or together to varying degrees. Although sciatica may not be the most specific descriptive term, it is useful as a catch-all descriptor of pain running down the back of the leg that seems to be related to a nerve root issue.

Should I get a scan?

Let’s revisit Dan’s MRI results: ‘Degenerative Disc Degeneration (DDD) at L4/L5 and L5/S1 and foraminal stenosis at L5, severe on the right and moderate on the left’.

If you’re familiar with the content on pain from Barbell Medicine, recall that the idea that pain always serves as a direct indicator of tissue damage is inaccurate [2,3]. Pain is much, much more complicated than this. As a result, determining an exact cause for low back pain or sciatica can be difficult because there is rarely one single cause that triggers pain symptoms. In fact, we often cannot reliably point to a physical problem with a bodily structure to explain why someone has back pain. The term “non-specific back pain” gets used in these cases, and it applies to the vast majority of cases of general back pain without clear radicular pain or radiculopathy [4].

Given that there is often not a single, specific site of tissue damage that can be confidently identified as the cause of a person’s pain, medical imaging may not always provide additional clarity or change how we approach or rehabilitate an injury.

While a bodily structure may not be obviously “broken” to cause someone’s symptoms, there are many other factors that can make things worse. For example, our expectations, feelings, and beliefs around our bodies can contribute to how we experience pain and how long it persists [5].

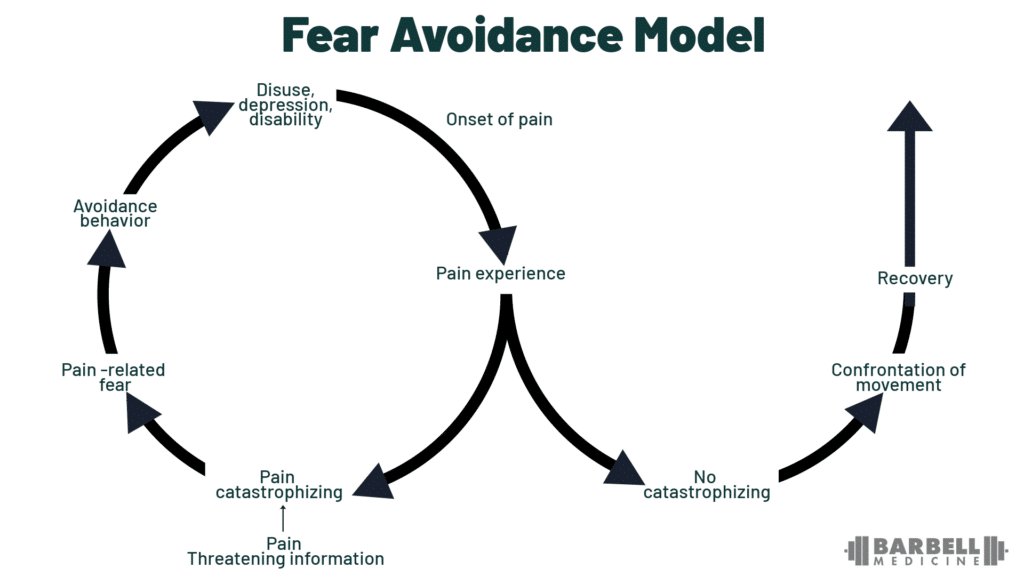

For example, if your healthcare provider says that you have ‘one of the worst backs’ they have ever seen after reviewing your MRI scan, and that you should ‘never flex your spine with anything more than 10 lbs’, that’s likely to cause quite a bit of fear around movement and physical activity in general. This pain-related fear can lead to a vicious cycle of avoiding physical activity, increasing physical disability, and a heightened pain experience as a result [6].

Credit: Bunzli et al 2017.

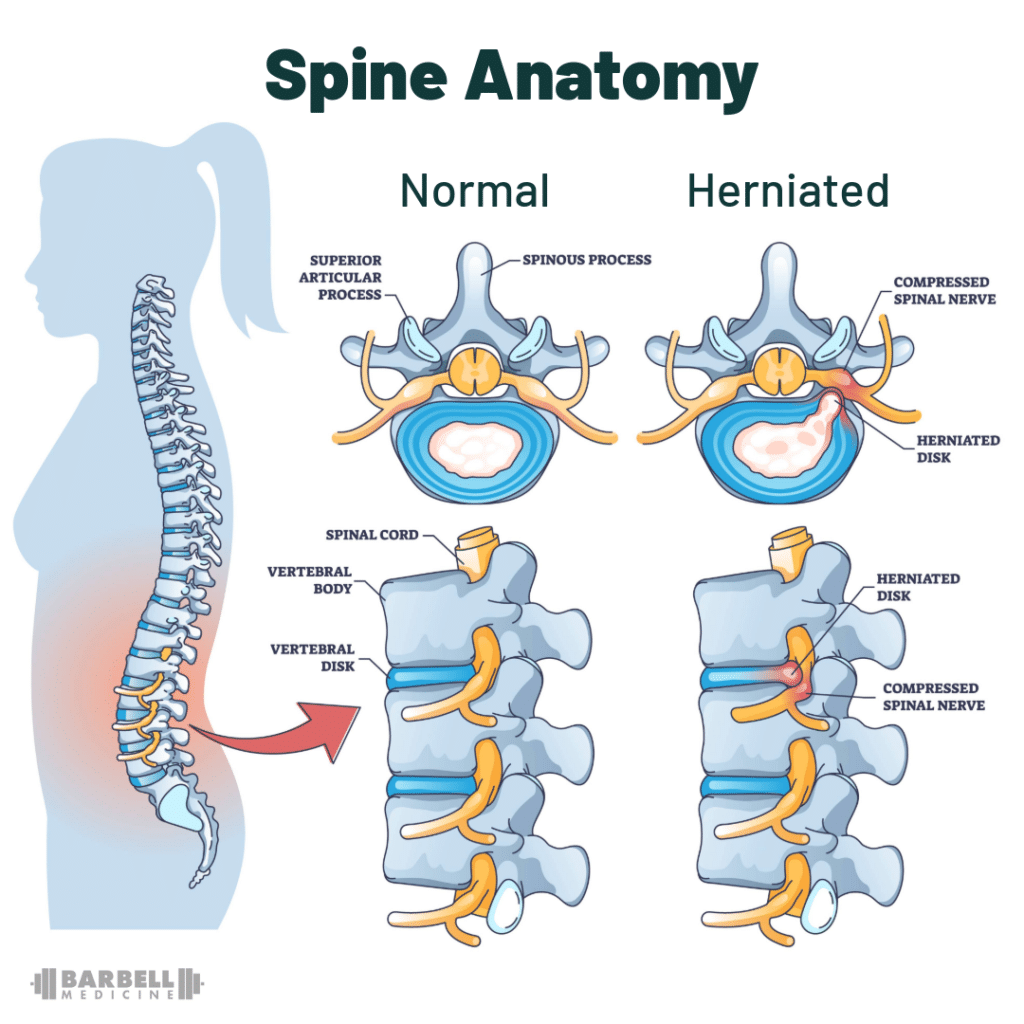

Herniated Disc

With that said, the most common imaging finding attributed to sciatica is a herniated intervertebral disc. This is where the gelatinous substance held within each disc, called the nucleus pulposus, pushes beyond the stiffer cartilage that forms the boundary of the disc, called the annulus fibrosus. The rigid ring of the annulus fibrosus is what keeps the nucleus pulposus intact and contained within the disc when forces are applied to the spinal column. This herniation of the nucleus pulposus causes irritation and inflammation of the surrounding nerve roots, and can lead to radiculopathy or radicular pain.

While this seems to make logical sense, herniated intervertebral discs are very common in people who have no back symptoms or dysfunction at all, and a majority of these heal on their own over time despite their reputation as a catastrophic injury [7]. In fact, “worse” herniations are more likely to heal [8,9] and the size of the herniation on MRI does not consistently correlate with radicular symptoms, suggesting that other factors can play a role in the severity of pain symptom — or whether they experience pain at all [10].

These are fascinating findings and are worth repeating: many people with disc herniations that can be seen on MRI scans did not know they had them and never experienced pain. Larger disc herniations, where more of the nucleus pulposus was squeezed out of the disc, not only healed and had the nucleus pulposus reabsorbed on repeat scans, but those larger herniations were more likely to heal than smaller herniations. Imaging is not destiny, and a scary looking MRI might have a better prognosis than the initial appearance might suggest.

Instead of viewing the body as a machine that is prone to breaking down or ‘wearing out’, understand that humans are very capable of adapting to the stress to which they are exposed, which often leads to these ‘changes’ seen on imaging. As a result, many tissue changes that we see on imaging scans reflect a lifetime of exposure and adaptation to a variety of stressors. This may partly explain the poor correlation between these findings on scans and symptoms like pain.

This is not to say that imaging findings have no relationship with pain. For example, in the case of lumbar radiculopathy (i.e., loss of nerve function including strength, sensation, or reflexes), there’s a good chance that there will be something ‘abnormal’ caught on a scan that explains the loss of nerve function. The key points here are that 1) imaging findings don’t tell the whole story, and 2) you can still achieve symptom relief without seeing ‘improvement’ or resolution on a scan [11]. Therefore, unless you plan on getting surgery or you fall into one of the categories mentioned in the next section, scans may not always be necessary, as it doesn’t change how we approach this problem from a non-surgical standpoint, it can be expensive, and can create unnecessary fear.

When Should I Seek Medical Attention For Back Pain?

While back pain can be frightening and make almost every movement unpleasant, it does not always require a visit to the doctor. However, there are some specific situations where getting professional help is wise. If you experienced a discrete event such as a slip, fall, or trauma followed by an inability to stand or bear weight, you should seek professional evaluation. If you are experiencing bowel or bladder problems like urinary incontinence, changes in urinary flow, or inability to urinate, or altered sensation between your legs (groin or “saddle” area) you should see a physician. If your low back pain is associated with unexplained weight loss, fevers, or you have a history of cancer, that necessitates further testing. If you are experiencing low back pain with radiculopathy or radicular pain down your leg that is getting progressively worse, you should be evaluated.

If those symptoms are present but not progressing, it does not require additional imaging, but does change the timeline some for resolution of symptoms. Typical “non-specific” low back pain resolves in 6 to 8 weeks, whereas the timeline for radicular symptoms is more variable. Among people with new radicular pain, about a third will improve dramatically within a few weeks, another third will experience a bit of improvement, and the last third will have symptoms that stay the same or worsen. The majority of improvement tends to occur within the first 3-4 months, although all of these timelines are averages, with significant variation from person to person. And of course, some people may experience a relapse in symptoms over the next year, although it will typically not be as severe.

Is Surgery Needed For Sciatica?

In some of the scenarios outlined above, surgery may be needed. For example, if someone fractured a bone due to a fall, or because of a tumor or infection, that requires more complex treatment. Cauda equina syndrome is a rare condition where the bundle of nerve roots located at the lower end of the spinal cord (called the cauda equina or “horse’s tail” in Latin) becomes compressed due to a herniated disc, tumor, infection, or fracture. This condition can involve symptoms such as a loss of bowel or bladder control, and requires emergency surgery.

Outside of those cases, there is evidence that surgery may provide better short-term relief and faster perceived recovery compared to non-surgical management in patients with severe levels of pain intensity. However, on average, long-term pain outcomes are similar whether a person gets surgery or not [12,13]. It is important to reiterate that in many cases there is hope for recovery without having to take on the potential risks and costs associated with surgery. Although the timeline may differ, it is often possible to make a full recovery with conservative management alone.

Knowing that outcomes tend to be similar over the long term on average, conservative management may be the better option for those with tolerable levels of pain intensity and higher confidence in their ability to self-manage the situation. For those who are in debilitating pain that is unrelenting, up-front surgical treatment may be the better option. Taken together, the decision for surgery will depend on each person’s situation and a thorough evaluation of the potential risks and potential benefits. It’s important to keep in mind that surgery doesn’t guarantee success, can be very costly, and carries the risk of other complications. Ultimately, this decision should be discussed with your medical doctor if surgery is a route you are considering.

How-To Use Exercise For Sciatica

The focus of this section will be centered on exercise as the primary means for conservative management, mainly because this approach places the emphasis on the individual to play an active role in their recovery. It’s important to note that there is no specific exercise that will guarantee everyone’s return to their desired activity. By the same token, there are no exercises that need to be avoided indefinitely after sustaining a low back injury or dealing with sciatica. Instead, we can think of exercises in terms of “symptom modification exercises” and “traditional exercises.”

Exercises For Sciatica

Symptom modification exercises are movements that are often unweighted or use light resistance, tend to be more limited in range of motion, and more isolated in the areas they target. They are aimed at reducing symptoms and improving function [14]. These types of exercises can be beneficial by allowing for non-threatening movement to build confidence, particularly if someone is experiencing significant pain.

Traditional exercises are the ones more associated with athletic development. They tend to be done with more challenging levels of resistance, use larger ranges of motion, and are broader in the muscles they train and their overall systemic effects. Weighted implement (barbell, dumbbell, kettlebell, etc.) and machine based resistance training, as well as more demanding body weight, calisthenic, and conditioning exercises would all be included here.

There are several different groups of symptom modification exercises that are often prescribed in the rehab world such as trunk strengthening, stretches for irritated nerves (typically called nerve glides or nerve flossing), repeated motions, or even walking. The mechanisms by which these exercises help to reduce symptoms are not entirely clear, and some of them may not work in the ways that are commonly thought. For example, trunk strengthening exercises are often prescribed to improve ‘core stability’ to help mitigate or prevent back pain. There are a few issues with this narrative. First, there is no clear definition of ‘core stability’, which makes it difficult to accurately assess and measure. Second, we don’t have good evidence that these types of exercises reliably mitigate risk of injury or improve performance more than any other kind of exercise [15]. Check out this article for a deeper dive on this topic.

Regardless of the mechanisms at play, the goal of symptom modification movements is to reduce discomfort and improve function. Experimenting with these movements can be useful to determine if there are any that provide significant relief. If so, including them in a daily routine or before a workout can help reduce sensitivity and allow for a better session overall. It’s important to note that while these exercises can help with symptoms in the short term, they are not a “necessary” component of recovery. The passing of time, patience, and graded exposure to the activities you want to do, are going to be much more important to the recovery process. Stated another way, what stands between you and being able to run, jump, and deadlift the way you want to is more dependent upon time and gradually introducing the more challenging traditional movements than elaborate rehab regimens.

Below is a table to illustrate the different categories of symptom modification exercises:

| Exercise Category | Example Exercises | Example Exercise Prescription |

|---|---|---|

| Trunk Strengthening | Bird dogs, planks, sit-ups | 2-4 sets x 10-20 reps |

| Nerve Glides | Sciatic nerve glides, femoral nerve glides | 10 sets x 5 second holds through a tolerable range of motion |

| Repeated Motions | Cobra push ups, Jefferson curls, cat-cow | 2-4 sets x 10-20 reps |

| General Movement | Walking, stretching, yoga | -Three 20 minute walks / day-3 sets x 30 second holds on selected stretches-Yoga routine of choice |

Lifting Weights With Sciatica

Based on an athlete’s goals, the incorporation of traditional exercises should likely be a part of rehabilitation from early in the process. Exercises can be scaled and modified to help find an entry point that is tolerable. To do this, modifying the rep ranges used, total volume, tempo, range of motion, and loading may be necessary.

Loading deserves special attention. At first, exercises will need to be significantly lighter and easier than what someone may have been used to before. This is where autoregulation, a concept in which the resistance or difficulty of an exercise is adjusted based on what a trainee can tolerate during a given session rather than arbitrarily selecting a weight, really shines.

One common method of autoregulation is the Rate of Perceived Exertion, or RPE. When using ratings of perceived exertion, a number from 1 to 10 is assigned to indicate a target level of difficulty, although in practice, anything less than 5 is rarely specified. In the context of lifting weights, RPE is closely tied to the idea of how many repetitions could be completed before performance failure. We have a full article on RPE that goes into a deeper dive on this too.

The table below summarizes rates of perceived exertion and how they correlate to repetitions in reserve, or repetitions before failure when lifting weights:

TABLE 2: Barbell Medicine Coach Tom Campitelli’s “Quick and Dirty Guide to Rate of Perceived Exertion” is a helpful illustration of the RPE scale. Note, this scale begins at 5 RPE, because it is rare to see prescriptions lower than this in your training program, but these may still be useful in the context of rehab.

When recovering from back pain, repetitions in reserve will not be related to muscular failure in the same way it may have been conceptualized prior to experiencing those symptoms. Instead, the rate of perceived exertion should shift to “repetitions in reserve from the individual’s tolerable threshold for pain.” Pain becomes the brake on exertion, rather than the pure ability of your muscles. When we say “tolerable symptoms,” we mean that levels of discomfort don’t spike to debilitating levels during the exercise session or the subsequent 24 to 48 hours.

FIGURE 4. Expected symptom fluctuations over time

For people who have more of a tendency to aggressively push through symptoms, using a tolerable threshold for pain might not be the best choice. It should be emphasized that there is a difference between training for maximum performance and training to get back to baseline.

For example, the normal anchor for a rating of perceived exertion of 8 is, “Could you perform two more repetitions at the selected weight before reaching performance failure?” In the context of pain, it may be more beneficial to ask whether you should do two more repetitions today, not just whether you could. The goal is to return to activity as quickly as possible. Sometimes, that means approaching early training sessions more gently.

Understanding this important difference is meant to encourage the trainee to be more conservative with load selection and can help to compensate for their tendency to push too hard too quickly. For these individuals, “undershooting” and doing things that feel too easy at first can paradoxically lead to more rapid pain improvement than by pushing more weight and doing more work.

If symptoms do increase dramatically during or after an exercise session, then modifications to the dosage or type of activity are probably required. This may involve altering the range of motion, changing exercise selection, or simply reducing the load or volume of activity to a more tolerable level and progressing from there.

Sciatica Rehab Exercise Examples

Many folks incorporating symptom modification exercises will enable the person to do additional exercise with more traditional movements. However, what exercises to pick, what reps to do, and how they should be loaded may not be clear.

Let’s do a few examples to put it all together.

_________

Denise is a 58 year old social worker who has been dealing with low back pain and occasional radiating pain down the back of her left leg and into her foot for the past 15 months. Her MRI showed evidence of possible nerve impingement between the fourth and fifth lumbar vertebrae (L4-L5). Her primary care provider gave her some general stretches and exercises to perform such as chair squats, clamshells, and a piriformis stretch. Her main goal is to overcome the pain she is experiencing so that she can engage in a consistent workout program and play with her grandkids without any limitations. She has a dumbbell set up to 50 lbs, bands, and an adjustable bench available at her home. She is able to train three times per week.

___

Troy is a 21 year old college student who recently had a low back flare up after a heavy set of deadlifts. He felt a ‘pop’ on the 3rd rep of a max effort set and had sharp, shooting pains that went down the back of his right leg just above his knee. He had to pull out from his planned powerlifting meet that was only two weeks away. For the past week he has been in a lot of pain and was told by his doctor to never lift again. Troy is understandably concerned and frustrated as his main goal is to be able to get back on the competition platform, which he feels may never be possible again. He currently trains at a powerlifting gym and has access to speciality bars, dumbbells, and a wide variety of machines. He wants to stick with a four times per week training frequency.

_________

Looking over these two cases, you can see how the initial approach is likely to be different just based on their goals, previous levels of activity, and access to equipment. Let’s look at a sample Week 1 program designed for both Denise and Troy respectively and we can discuss the details more in depth.

Let’s start with Denise.

At-Home Workout Plan For Sciatica

For Denise’s initial program, each session begins with some isolation work or a symptom modification exercise prior to her main movements. The idea is to warm up her back, decrease sensitivity, and gain confidence before moving into her main exercises.

Given her equipment availability, her lower body movements are all programmed using dumbbells, a slower tempo, and higher rep range, which should keep loads light enough to where she can move comfortably and find an entry point with less risk of aggravating symptoms.

| Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 |

|---|---|---|

| Goblet Good Morning Tempo: Slow and controlled 3 sets x 15 reps @ RPE 6 | Cat-Cow Exercise 3 sets x 20 reps | Sphinx pose 3 sets x 10 reps w/ 5 second holds for each rep |

| Goblet Squat Tempo: 3.1.0 = 3 sec on the way down, 1 sec pause in the bottom, normal speed on the ascent 12 reps @ RPE 512 reps @ RPE 612 reps @ RPE 7 | Single Leg Romanian Deadlift Tempo: Slow and controlled 12 reps @ RPE 512 reps @ RPE 612 reps @ RPE 7 / side | Single Leg Hip Thrust Tempo: Slow and controlled 12 reps @ RPE 512 reps @ RPE 612 reps @ RPE 7 / side |

| Feet Up Dumbbell Bench Press Tempo: Normal 10 reps @ RPE 510 reps @ RPE 610 reps @ RPE 7 | Seated Dumbbell Press Tempo: Normal 10 reps @ RPE 510 reps @ RPE 610 reps @ RPE 7 | Split Squat Tempo: Normal 12 reps @ RPE 512 reps @ RPE 612 reps @ RPE 7 / side |

| Walk 25 minutes at talking pace | Walk 25 minutes at talking pace | Bench Dips 3 sets to RPE 9 |

| Walk 25 minutes at talking pace |

Her selected upper body movements are feet up dumbbell bench press, seated dumbbell press, and bench dips. Each of these should be pretty manageable for her to get into position and execute. Using the feet-up bench press or seated version of the overhead press can be beneficial for folks who are sensitive to extending the low back such as arching in the bench press or leaning back when overhead pressing from a standing position.

Each session concludes with a light 25 minute walk to help with building more capacity for activity and reducing symptoms.

Gym Workout Plan For Sciatica

Following a similar structure to Denise’s initial program, each of Troy’s training days starts off with a symptom modification movement prior to moving into his main work aside from Day 4.

Day 4 is more of an accessory day using machine exercises like leg extensions that he can train closer to failure without much risk of aggravating his back. Working through the rehab process, using more bodybuilding style machine work can be very beneficial in satiating an athlete’s desire for a good workout without making symptoms worse.

For Troy’s lower body work, box squat variations are being used to limit range of motion due to sensitivity with squatting through a full range of motion, even with body weight. Higher rep schemes and slower tempos were chosen again here to help with keeping loads lighter during the first few sessions.

| Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 | Day 4 |

| Barbell Good Morning Tempo: Slow and controlled 3 sets x 15 reps @ RPE 6 NOTE: Move through a tolerable range of motion | Curtsy Lunge 3 sets x 12 reps @ RPE 7 / side | Barbell Good Morning Tempo: Slow and controlled 3 sets x 15 reps @ RPE 6 NOTE: Move through a tolerable range of motion | Leg Extensions + Leg Curls 3 sets x 10-15 reps @ RPE 8-9 |

| High Bar Box Squat Tempo: 3.1.0 = 3s on the way down, 1s pause on the box/bench 10 reps @ RPE 510 reps @ RPE 610 reps @ RPE 7 | Romanian Deadlift Tempo: Slow and controlled 12 reps @ RPE 512 reps @ RPE 612 reps @ RPE 7 NOTE: Move through a tolerable range of motion | Low Bar Box Squat Tempo: 3.1.0 = 3s on the way down, 1s pause on the box 6 reps @ RPE 56 reps @ RPE 66 reps @ RPE 7 NOTE: Move through a tolerable range of motion | Back Extensions Tempo: Slow and controlled 3 sets x 12-15 reps @ RPE 6-7 NOTE: Move through a tolerable range of motion |

| Belt Squat Tempo: Normal 5 reps @ RPE 65 reps @ RPE 75 reps @ RPE 8 2 sets x 8 reps @ 10-15% load drop | Seated Barbell Press Tempo: Normal 10 reps @ RPE 510 reps @ RPE 610 reps @ RPE 7 | Leg Press/Hack Squat Tempo: Normal 10 reps @ RPE 610 reps @ RPE 710 reps @ RPE 8 | Chest Press Machine Tempo: Normal 10 reps @ RPE 610 reps @ RPE 710 reps @ RPE 8 |

| Feet Up Bench Press Tempo: Normal 6 reps @ RPE 56 reps @ RPE 66 reps @ RPE 7 x 2 sets | Rear Foot Elevated Split Squat 3 sets x 12 reps @ RPE 8 / side | Feet Up Bench Press Tempo: 1s pause on the chest 2 reps @ RPE 52 reps @ RPE 62 reps @ RPE 7 2 sets x 5 reps @ 10-15% load drop | Upper body accessories (upper back, shoulder isolation, arms) 2-3 sets x 8-15 reps @ RPE 8-9 |

| Walk 25 minutes at talking pace | Walk 25 minutes at talking pace | Walk 25 minutes at talking pace | Walk 25 minutes at talking pace |

The idea is to be able to complete each session without a significant increase in symptoms. The more small successes like this that can be strung together in training, the more confidence a trainee will build. This starts to put them in control of their back pain and can be enormously empowering.

As mentioned earlier in the article, many variables besides damage to tissues can impact how we experience pain. This feeling of exercising control over our situation, accumulating successes through exercise, and observing increased capacity to perform physical activity can help us to hurt less and feel safer with movement. Our feelings about our pain and injury have a profound effect on how much pain we are in. This is one way in which activity helps us resolve symptoms. Yes, we heal over time. We also convince ourselves that we can do more work while not reinjuring ourselves. With that aside, we will return to some of the decisions that inform Troy’s program.

The leg press and belt squat are included so that Troy can get a good training stimulus for his legs with less risk of irritating his back. A Romanian deadlift through a tolerable range of motion was selected so that he doesn’t have to start from the floor and can more easily self-select the range of motion he uses based on tolerance.

His upper body work is pretty similar to what he was doing prior to injury, just with feet up variations and no dumbbell work as he struggles to set up with an arch and to move the dumbbells in place to begin pressing. Each session concludes with a 25 minute walk to build more capacity for activity.

An interesting parallel between both Denise and Troy is that some symptom modification exercises are included both before and after the main parts of their training sessions. Their programs differ quite a bit as far as what those symptom modification and traditional exercises are, as well as how they are loaded and how much volume is prescribed. This makes sense because they are different humans with different training histories and physical capacities. However, there are common themes here.

Specifically, these programs start gently and appropriately and, in Troy’s case especially, represent a lowered level of intensity of activity. The goals are to manage symptoms and make progress from where they currently reside, rather than prematurely trying to force them back to full functioning or go after weights and exercises they were performing prior to their injuries. The symptom modification exercises are used as an appetizer and a dessert, rather than representing the entirety of what they do. Traditional exercises, and variants thereof, are part of the program from early on. For exercises that don’t meaningfully aggravate their back pain, fewer, if any, modifications are included. This helps to reinforce the idea that they can do these things and provides a clearer path back to where they want to be, in addition to facilitating the recovery process.

Hopefully these case examples have provided more insight on how to continue training with a low back injury and facilitating recovery towards the activities you want to get back to. Keep in mind that there are many different approaches that can be beneficial for navigating low back symptoms and promoting recovery. There are also many different ways to apply the principles of load management, pain science, and autoregulation from above to design a program.

The key idea is that these are simply two approaches to the problem of back pain, not The Approach. By understanding the principles, you can more effectively filter out the overwhelming amount of information that’s out there to make more informed decisions.

Need A Helping Hand?

If designing your own program seems overwhelming and you’re unsure where to start, our low back pain rehab template is a good starting point. If you continue to experience symptoms, our pain and rehab team offers consultations and rehab focused programming that is tailored to your specific situation. We would be more than happy to help.

Author Bio

Written by Charlie Dickson, doctor of physical therapy, and world champion powerlifter. Working as both a performance coach and rehab clinician on the Barbell Medicine team, I’ve had the opportunity to consult with and guide a large number of individuals through their experience of low back pain and ‘sciatica’ over the years. I’ve also had the unfortunate experience of going through my own struggles with low back pain and sciatica.

Special thanks to Dr. Austin Baraki, Dr. Jordan Feigenbaum and Thomas Campitelli for editing this article.

References:

[1] Bogduk N. On the definitions and physiology of back pain, referred pain, and radicular pain. Pain. 2009 Dec 15;147(1-3):17-9. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.08.020. Epub 2009 Sep 16. PMID: 19762151.

[2] Moseley, Lorimer. (2007). Reconceptualising pain according to modern pain science. Physical Therapy Reviews. 12. 169-178. 10.1179/108331907X223010.

[3] Cohen, Miltona,*; Quintner, Johnb; van Rysewyk, Simonc. Reconsidering the International Association for the Study of Pain definition of pain. PAIN Reports 3(2):p e634, March/April 2018. | DOI: 10.1097/PR9.0000000000000634

[4] Hartvigsen J, Hancock MJ, Kongsted A, Louw Q, Ferreira ML, Genevay S, Hoy D, Karppinen J, Pransky G, Sieper J, Smeets RJ, Underwood M; Lancet Low Back Pain Series Working Group. What low back pain is and why we need to pay attention. Lancet. 2018 Jun 9;391(10137):2356-2367. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30480-X. Epub 2018 Mar 21. PMID: 29573870.

[5] Setchell J, Costa N, Ferreira M, Makovey J, Nielsen M, Hodges PW. Individuals’ explanations for their persistent or recurrent low back pain: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2017 Nov 17;18(1):466. doi: 10.1186/s12891-017-1831-7. PMID: 29149847; PMCID: PMC5693501.

[6] Bunzli S, Smith A, Schütze R, Lin I, O’Sullivan P. Making Sense of Low Back Pain and Pain-Related Fear. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2017 Sep;47(9):628-636. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2017.7434. Epub 2017 Jul 13. PMID: 28704621.

[7] Brinjikji W, Luetmer PH, Comstock B, Bresnahan BW, Chen LE, Deyo RA, Halabi S, Turner JA, Avins AL, James K, Wald JT, Kallmes DF, Jarvik JG. Systematic literature review of imaging features of spinal degeneration in asymptomatic populations. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2015 Apr;36(4):811-6. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A4173. Epub 2014 Nov 27. PMID: 25430861; PMCID: PMC4464797.

[8] Chiu CC, Chuang TY, Chang KH, Wu CH, Lin PW, Hsu WY. The probability of spontaneous regression of lumbar herniated disc: a systematic review. Clin Rehabil. 2015 Feb;29(2):184-95. doi: 10.1177/0269215514540919. Epub 2014 Jul 9. PMID: 25009200.

[9] Zhong M, Liu JT, Jiang H, Mo W, Yu PF, Li XC, Xue RR. Incidence of Spontaneous Resorption of Lumbar Disc Herniation: A Meta-Analysis. Pain Physician. 2017 Jan-Feb;20(1):E45-E52. PMID: 28072796.

[10] Karppinen J, Malmivaara A, Tervonen O, Pääkkö E, Kurunlahti M, Syrjälä P, Vasari P, Vanharanta H. Severity of symptoms and signs in relation to magnetic resonance imaging findings among sciatic patients. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2001 Apr 1;26(7):E149-54. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200104010-00015. PMID: 11295915.

[11] Benson RT, Tavares SP, Robertson SC, Sharp R, Marshall RW. Conservatively treated massive prolapsed discs: a 7-year follow-up. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2010 Mar;92(2):147-53. doi: 10.1308/003588410X12518836438840. Epub 2009 Nov 2. PMID: 19887021; PMCID: PMC3025225.

[12] Peul WC, van Houwelingen HC, van den Hout WB, Brand R, Eekhof JA, Tans JT, Thomeer RT, Koes BW; Leiden-The Hague Spine Intervention Prognostic Study Group. Surgery versus prolonged conservative treatment for sciatica. N Engl J Med. 2007 May 31;356(22):2245-56. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa064039. PMID: 17538084.

[13] Fernandez M, Ferreira ML, Refshauge KM, Hartvigsen J, Silva IR, Maher CG, Koes BW, Ferreira PH. Surgery or physical activity in the management of sciatica: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Spine J. 2016 Nov;25(11):3495-3512. doi: 10.1007/s00586-015-4148-y. Epub 2015 Jul 26. PMID: 26210309.

[14] The Role and Value of Symptom-Modification Approaches in Musculoskeletal Practice. Gregory J. Lehman. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy 2018 48:6, 430-435

[15] Wirth K, Hartmann H, Mickel C, Szilvas E, Keiner M, Sander A. Core Stability in Athletes: A Critical Analysis of Current Guidelines. Sports Med. 2017 Mar;47(3):401-414. doi: 10.1007/s40279-016-0597-7. PMID: 27475953.